E-learning literacy

Introduction

e-learning literacy (or e-learning competency) measures the extent to which someone is able to participate in e-learning activities. In this article we define e-learning in a wide perspective, i.e. including all forms of digital learning such as rapid e-learning, academic conversational blended learning, MOOCs, interactive multimedia, classroom technology, etc.

E-learning programs often fail in one way or another to meet expectations. One of the reasons could be the lack of what we could call e-learning literacy. Another reason, is that e-learning often is used as an opportunity for changing learning goals, for example put more emphasis on "deep learning", which asks more from learners.

E-learning literacy, also known as online learning skills or e-learning skills, e-learner competency, e-learning readiness, distance learner competence, blended learner competence, etc., refers to skills, knowledge, attitudes and behavior sets that are necessary to participate in partial or full online learning programs and classes. Hong and Jung (2010) [1] define distance learner competencies’ “as knowledge, skills and attitudes that enable a person to be a successful distance learner [...] A successful distance learner is operationally defined as a distance learner who has completed distance courses at least three semesters, with above average grades”. This definition also could be used to defined competency for blended learning.

E-learning literacy comprises several literacies, for example:

- Digital literacy (or literacies), e.g. computer literacy and information literacy

- Metacognitive literacy, defined as metacognitive skills, in particular appropriate learning strategies and Self-regulation and planning skills

- Academic integrity competence, e.g. plagiarism

E-learning is strongly related to flexible and distance learning and the skills required to follow a contemporary online or blended class are e-learning skills. According to Hong and Jung (2010) [1],

Ho et al. (2010) [10], in a small literature review, identify several components of e-learner competency and also point out one also should consider e-learning readiness which refer to more general "prior" variables and are adopted from Watkins (2005) [11] E-learning readiness includes: technology access, online skills and relationships, motivation to learn, internet forum skills, etc., i.e. a mix of digital literacy skills, available technology and motivational factors.

Ho et al (1010) adopt the Birch (2010) [12] model which consists of three factors: “

- Self‐direction competency: refers to e‐learners' ability in self‐advocacy, self‐sufficiency, self‐confidence.

- Meta‐cognitive competency: refers to e‐learners' higher‐order thinking involving active control over the cognitive processes engaged in learning and self‐evaluation process.

- Collaborative competency: refers to the skills needed when participating in synchronous or asynchronous online learning activities, which includes chat sessions, email exchanges, discussion threads, instant message and virtual classrooms.”

Stary and Wichhart (2012) stress the importance of well integrated digital literacy skills.

When students become responsible for designing their individual learning processes, e-learning literacy has to be considered an umbrella term, as it requires the capability to identify and organize information by means of information and communication technologies for learning purposes (cf. Di Sessa, 2001). As such, it comprises information and digital media literacy. Information and communication technologies are assumed to support learners of different types and teachers hereby (Tham & Werner, 2005). Learning literacy, and to be educated about learning (cf. Souto-Manning & Swick, 2006), are deceptively simple phrases as they imply an established and manageable set of (meta-cognitive) skills. If such skills are acquired it would make one knowledgeable about learning and guiding learning processes. [[..]] When the focus is on e-learning, additional skills are needed to operate instruments or tools. This skill set includes creating, finding, selecting, filtering, marking, managing, and transferring information for online reading, documenting, and communicating with peers online, along with those skills needed to navigate network spaces.

Summarized the authors suggest that:

- People who are to be responsible for their own learning do need ICT, media and learning literacy.

- E-learning requires extra skills such as online information and communication skills.

E-learning competences in a wider context

Sometimes e-learning competency is negatively defined as part of "barriers to e-learning". E-learning competency is also addressed in the large literature on e-learner satisfaction, e-learning management, etc. and is treated as of type of explanatory variable. Seen in a wider context, e-learning competency does not by itself predict success. Other variables such as various personality traits, the learning environment, etc. intervene. A probably important personality trait is grit.

Alexander (2001) [14] summarize a few variables that can influence the student's experience of e-learning. Some of these are related to e-learning skills, for example:

- Time available to devote to the course (e.g. Weller and Mason, 2000 [15]). Time is the "new distance", i.e. if students cannot manage time, they will give up.

- Familiarity with new pedagogical designs. This implies that “students need to be briefed on the views of learning which underpin particular learning strategies, and encouraged to be reflective about their own learning.”

- Group work skills. Since few students have experience of group work, teachers “should undertake preparatory work for the activity, and opportunities should be provided for support of the activities and de‐briefing of the experience.”

Daniel (2016) [16] in his Making Sense Of Blended Learning: Treasuring An Older Tradition Or Finding A Better Future? report, summarizes some research on student perceptions in technology-based learning and identifies four main factors that compose student's attitudes to technology-based learning.

First, a cultural tradition where students are used to learning by rote and reproducing the knowledge thus acquired through conventional tests is not a good environment for introducing online learning - or at least not without significant planning and preparation by institutions and faculty.

Second, high achievers take to blended learning more readily than low achievers - which is probably true of almost any pedagogical innovation. The more students experience blended learning the better they perform.

Third, both blended and online offerings stimulate students to work harder and engage more fully with the course.

Fourth, sound pedagogy, especially very clear signposting of what students are expected to do, is essential to the success of online teaching. Also, where technical standards are not met, students tend to have a very negative experience of the course (Uvalić-Trumbić & Daniel, 2013).

- - Daniel (2016:10) [16]

Paechter (2010) et al. [17] notice that student expectations and experiences are related to (the perception of) learning achievement and course satisfaction. Some of the expectations concern flexibility, self-regulation, internet skills and communication knowledge. More precisely, students expect flexibility in the choice of learning strategies and opportunities for self-regulation. They also expect to acquire media competence. “Few variables contribute to perceived learning achievements in a course, specifically expectations of learning achievements, flexibility of learning, and the exchange of knowledge with peer students.”

Sun et al. (2008) [18] found in their study on user satisfaction that “learners’ computer anxiety, instructor attitude toward e-Learning, e-Learning course flexibility, e-Learning course quality, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and diversity in assessment are the critical factors affecting learners’ perceived satisfaction. Together, these seven factors are able to explain 66.1% of the variance of user satisfaction.”. Except for "computer anxiety, none of these relate to perceived e-learning competence.

Components

Main components for learners

E-learning literacy or competency is probably composed of the following large categories:

- Digital literacy, that can be further decomposed into computer literacy (ICT literacy), network literacy, social media literacy and Information literacy: Find, sort and use information

- Metacognitive literacy, in particular Self-directed learning: Set goals, plan and implement learning activities, time management

- Communication and collaboration literacy: working in groups, asking help from tutors, contribute to a larger community, etc.

- Extra skills related to specific e-learning procedures and culture: Use an e-learning environment, understand how to interact, understand one's role in a scenario, etc.

In order to define components of e-learning competency we probably also should look at connected areas, for example distance learning, and for two main reasons: "e-learning" sometimes is defined in a narrow way and does not include all forms of digital learning. Research in connected areas can include topics that are not covered or not well covered in e-learning literacy research. In particular, the literature on distance learning and digital literacy seems to be much better developed.

Bates (2015) [19] based on Employability Skills 2000+ by the conference board of Canada identifies a list of 7 skills that match the need of knowledge workers and that should be developed within a curriculum. We argue that these skills to be taught to future citizens and knowledge workers are the same as the skills that are needed to successfully engage in digital learning of various kinds.

- Communications skills: as well as the traditional communication skills of reading, speaking and writing coherently and clearly, we need to add social media communication skills. These might include the ability to create a short YouTube video to capture the demonstration of a process or to make a sales pitch, the ability to reach out through the Internet to a wide community of people with one’s ideas, to receive and incorporate feedback, to share information appropriately, and to identify trends and ideas from elsewhere;

- the ability to learn independently: this means taking responsibility for working out what you need to know, and where to find that knowledge. This is an ongoing process in knowledge-based work, because the knowledge base is constantly changing. Incidentally I am not talking here necessarily of academic knowledge, although that too is changing; it could be learning about new equipment, new ways of doing things, or learning who are the people you need to know to get the job done;

- ethics and responsibility: this is required to build trust (particularly important in informal social networks), but also because generally it is good business in a world where there are many different players, and a greater degree of reliance on others to accomplish one’s own goals;

- teamwork and flexibility: although many knowledge workers work independently or in very small companies, they depend heavily on collaboration and the sharing of knowledge with others in related but independent organizations. In small companies, it is essential that all employees work closely together, share the same vision for a company and help each other out. In particular, knowledge workers need to know how to work collaboratively, virtually and at a distance, with colleagues, clients and partners. The ‘pooling’ of collective knowledge, problem-solving and implementation requires good teamwork and flexibility in taking on tasks or solving problems that may be outside a narrow job definition but necessary for success;

- thinking skills (critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, originality, strategizing): of all the skills needed in a knowledge-based society, these are some of the most important. Businesses increasingly depend on the creation of new products, new services and new processes to keep down costs and increase competitiveness. Universities in particular have always prided themselves on teaching such intellectual skills, but the move to larger classes and more information transmission, especially at the undergraduate level, challenges this assumption. Also, it is not just in the higher management positions that these skills are required. Trades people in particular are increasingly having to be problem-solvers rather than following standard processes, which tend to become automated. Anyone dealing with the public needs to be able to identify needs and find appropriate solutions;

- digital skills: most knowledge-based activities depend heavily on the use of technology. However the key issue is that these skills need to be embedded within the knowledge domain in which the activity takes place. This means for instance real estate agents knowing how to use geographical information systems to identify sales trends and prices in different geographical locations, welders knowing how to use computers to control robots examining and repairing pipes, radiologists knowing how to use new technologies that ‘read’ and analyze MRI scans. Thus the use of digital technology needs to be integrated with and evaluated through the knowledge-base of the subject area;

- knowledge management: this is perhaps the most over-arching of all the skills. Knowledge is not only rapidly changing with new research, new developments, and rapid dissemination of ideas and practices over the Internet, but the sources of information are increasing, with a great deal of variability in the reliability or validity of the information. Thus the knowledge that an engineer learns at university can quickly become obsolete. There is so much information now in the health area that it is impossible for a medical student to master all drug treatments, medical procedures and emerging science such as genetic engineering, even within an eight year program. The key skill in a knowledge-based society is knowledge management: how to find, evaluate, analyze, apply and disseminate information, within a particular context. This is a skill that graduates will need to employ long after graduation.

- The skills needed in a digital age Bates (2015) [19]. Copyright: Bates (2015). Contents of this table are available under the CC BY-NC licence.

In a three-phased empirical study, Hong and Jung (2010) [1] identified the following distance learning skills which probably are relevant for most if not all e-learning variants:

| Clusters | Competencies |

|---|---|

| Study vision |

|

| Cognitive and meta-cognitive skills |

|

| Interaction abilities |

|

| Identity as learner |

|

| Management skills |

|

In their discussion, the authors also point out that “technology-related skills are not included in the competency list except the competency to manage available resources including time, information and media/technology effectively.This highlights the importance of selecting and using media and technology appropriately. But other specific technology-related skills do not appear to be critical to the successful distance learner. This finding counters previous studies rating the importance of technology competency.” The authors explains this by a growing digital literacy in the population and we would add that (traditional structured) distance teaching does not require an enormous amount of more advanced Internet skills. The same also can be said for Interaction abilities which in their study is weakly correlated with the other scales.

By e-learning course component

E-learning skills also can be tied to various course components, e.g.

- Using courseware

- Engaging in learning activities (tasks)

- Communication between learners and learners and learners and tutors (in particular "non-scripted one")

- Understanding course-level outcomes

- Understanding expectations (in particular, deliverables, i.e. evaluated student productions)

- Finding and using extra contents

- Time management (in particular, deliverables)

- Dealing with student assessment and course evaluation

Variants of e-learning

According to the e-learning type, literacy requirements may be different, e.g. Jara and Fitri (2007) [20] identify the following types and subtypes:

- Blended:

- B1: Online admin support: Core teaching is face to face, organization + materials put online

- B2: Follow-up: Core activities are face-to-face, but additional online activities are provided

- B3: Parallel, Some activities face-to-face, others online

- B4: Face-to-face events: Core activities are online, but some are face-to-face.

- Distance:

- D1: Distance online support: print-based courseware + online tutoring

- D2: Online resource based: online activities organised around resources

- D3: Online discussion based: online activities organised around discussions

- D4: MOOCS (our addition, a variant of D1): Videos + peer-tutored activities

We hypothesize that the B4 and D1, D4 variants require higher self-direction skills. B2/3 and D2/3 require higher communication and social media skills.

Developmental models

E-learning competence also can be defined in developmental perspective.

Bettham and Sharpe

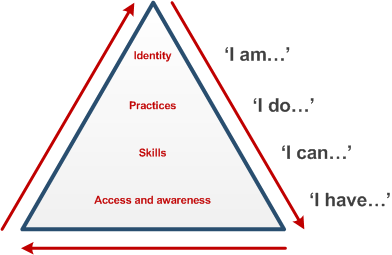

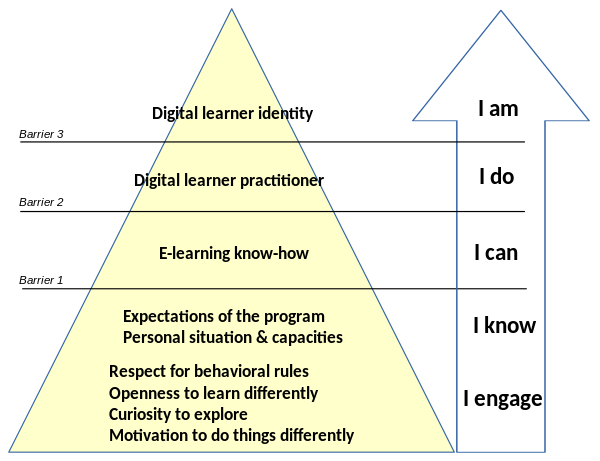

According to JISC (2014) [21], Beetham and Sharpe (2010) developed a ‘pyramid model’ of digital literacy development. This model is fairly universal and also could be used to structure development of e-learning competence. “Beetham and Sharpe’s framework (2010) describes digital literacy as a development process from access and functional skills to higher level capabilities and identity.” (Developing digital literacies (retrieved, May 13 2019).

The figure below includes a more differentiated picture

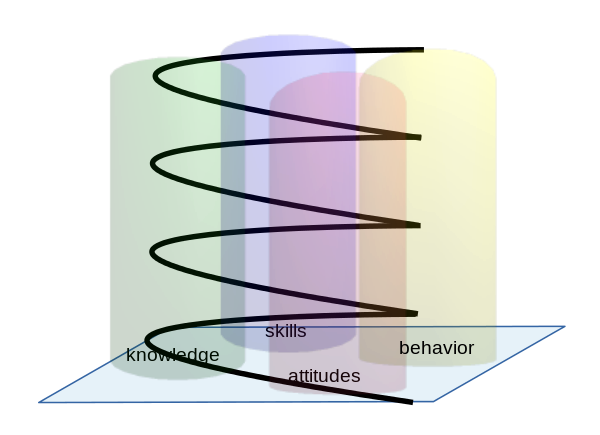

However, Pyramid models do not take into account that development is circular, i.e. takes a form of "spiral". For example, acquiring and changing some attitudes, knowing more "about" e-learning, acquiring a performance level for some skills can bring a learner to a certain level (i.e. be able to follow a self-learning class or a project-oriented blended design). These skill sets are domain restricted. More general e-learning "intelligence" (i.e. being able to understand all sorts of e-learning requirements, and to adapt and engage in successful learning) probably will be developed after experiencing and learning from multiple classes.

Since we consider that becoming an e-learner is a kind of acculturation process, some cultural competence models could and should be adapted to e-learning. In particular, developmental and cultural intelligence (CQ) models could help formulating some essential mechanisms of become a proficient e-learner.

At this point we also would like to recall the difference between competence defined as skill sets and competence defined as a kind of intelligence that allows people to deal with new situations. It can be argued that the most important e-learning competence is the ability to participate online and the ability or inability to do so is the "new divide" in using ICT. Lin et al. (2013) [22] presented a two-dimensional "New Media literacy" framework consisting of functional consuming vs. critical consuming, and functional prosuming vs. critical prosuming literacies. We adapted this model - presented int the digital literacy article, to the context of e-learning.

Both component models and developmental models are necessary and both need to be completed by a situated perspective that takes into account contexts and their affordances. (... to do ...)

Adaptive expertise (to do)

Initial student expectations and skills

In a provisional document, Helen Beetham present the findings of a 2013 JISC study on Students' expectations and experiences of the digital environment and that included a literature review, stakeholder interviews, institutional interviews, student interviews and student focus group. Below, we summarize a few points:

- Students' expectations and preferences regarding the digital environment for study show that they have fairly high expectations, but are unclear about the available services and the technologies they will use.

- Findings on students' experiences of learning in a digital study environment indicate that their expertise is very diverse and that they tend not to use more sophisticated applications unless directed to do so. In the same vein, personal digital competences need adaptation to the academic context.

- Findings on engaging students in dialogue about their digital experiences and expectations shows that students should and can be engaged in developing sustainable practices and infrastructures.

- Findings on priority areas for further investigation show that (initial) expectations are very diverse and that these do not necessarily correlate with what they need to succeed.

Strategies to ease the e-learning literacy burden

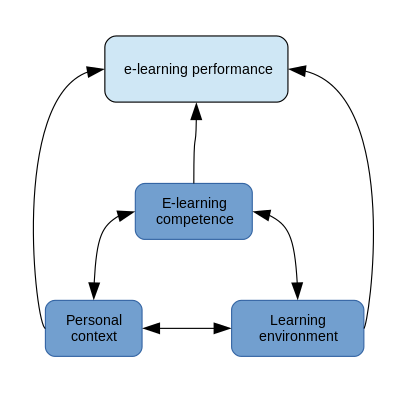

We postulate that e-learning performance is a result of three connected factors: e-learning competency, the personnel context (e.g. available resources, personality traits like grit) and the learning environment. Moreover these three factors are related within themselves.

This figures implies that (a) we should help the learners to develop their e-learning competence, (b) the learning environments should be designed with good user experience principles in mind and (c) that external constraints (such as available time or family support) also play a role. Moreover both personal contexts and the learning environment could contribute to the development of e-learning literacy and the other way round.

Strategies to reduce and ease the e-learning burden

There exist many strategies to ease the burden, i.e. the various literacy requirements. For example:

- Organize an e-learning class like a traditional class. An example are MOOCs that use regular schedules, video lectures, light-weight assignments, etc. However, this strategy does have its drawbacks, i.e. it keeps the typical learner passive.

- Include contents (courseware) that is didactically structured.

- Use pedagogical scenarios that include strong "scripting" (sequencing of learning activities)

- Negotiate a learning contract, e.g. use strategies like intelligibility catchers.

- Tutoring (including coaching, counseling, feedback, help, etc.)

- Encourage creation of an online community and improve feeling of social presence. Alternatively or also encourage students to create their own.

- Reduce initial anxiety and inhibitions, e.g. though some "icebreaking activity".

- Avoid negative incidents ([23]

- Pay attention to the ergonomics of the environment

- Add elements that increase motivation and self-efficacy

- Support communication and "modeling" with/from other students.

- Integrate emotional factors

- ...

However, decreasing cognitive load of tasks is not always appropriate, since increasing e-learning skills (and more generally digital literacy may be a course-level outcome. In other words, students should sometimes be exposed to difficulty and that may also include extrinsic cognitive load. Higher-level learning requires a construction effort from the learner, a process that can be enhanced through various types of cooperative, collaborative and collective learning activities. There may be a contraction between "easing" the task and learning goals in higher education. “Bereiter and Scardamalia (2003)[24] point out that if we want students to acquire the skills needed to function in knowledge-based, innovation-driven organizations, we should place them in an environment where those skills are required in order for them to be part of what is going on.” (cited by [25])

Klein et al. (1998:2) [26] define the interesting concept of cognitive demands analysis': “Whereas cognitive task analysis attempts to identify the cognitive skills an individual uses or needs to perform a task proficiently (Klein, 1995; Means & Gott, 1988; Roth & Mumaw, 1995), a cognitive demands analysis seeks to describe the types of cognitive learning expected of the individual by the technology”. This does not just include contents but also the “types of activities and instructional opportunities in which students are expected to engage”. The authors identify five families of cognitive learning: content understanding, collaboration, communication, problem solving, and metacognition.

Quality standards and bills of rights

E-learning quality standards

Quality standards for educational programs in general, and technology-based and distance learning ones in particular, may attempt to increase the e-learning experience, e.g. by lowering certain hurdles.

Frydenberg (2002) [27] analysed quality dimensions in a number of quality models for e-learning, and she proposed nine criteria areas as domains of e-learning quality. They are as follows: executive commitment, technology infrastructure, student services, instructional design and course development, instruction and instructor services, financial health, program delivery, legal and regulatory requirements and program evaluation. (Cited by Ossiannilsson (2015:20) [28]).

The Seequel bill of rights

EIfEL (European Institute for E-Learning) was an independent, not-for-profit European professional association in the area of "knowledge society". It was leading the Europortfolio consortium and was a founding member of EFQUEL, the European Foundation for Quality in E-Learning. In the context of the Sustainable Environment for the Evaluation of Quality in E-Learning - SEEQUEL (broken link) project, an elearning bill of rights was developed. [29]

Below is an excerpt containing the "short definitions" of each right:

- Access to learning: open and equal access to education, training and other learning opportunities

- Information on learning provision: full and accurate information on learning provision

- Learning guidance: open information and guidance on all aspects of adult education, opportunities and rights

- Learning Administration: fast, efficient and courteous administration

- Learning support staff: be supported by qualified and competent staff who are actively engaged in their continuing professional development

- Learning environment: a suitable, accessible and state of the art learning environment facilitating peer support

- ePortfolio: an ePortfolio to plan, and manage learning, and value one’s assets within communities

- Learning activities: learning which is relevant to learners’ lives

- Learning resources: appropriate learning resources to facilitate self- directed learning

- Occupational standards: accurate and up-to-date occupational standards

- Planning learning: participate or be appropriately represented in planning learning activities

- Prior learning: prior learning recognition

- Learning induction: appropriate induction to a programme or a resource

- Learning strategies: a personalised and balanced range of learning and teaching strategies

- Self-directed learning: personal control over the learning experience

- Monitoring and assessment: a fair and transparent assessment process

- Feedback & complaints: a fair and effective feedback and complaints procedure

Such a bill of right does imply that the learners are (a) aware of these rights and (b) that they do have the competency to use it. E.g. using support staff, and ePortfolio, be able to do self-directed learning may be right, but not an acquired competence. In other words, e-learning rights may have to be taught ...

General quality standards

In addition to e-learning specific quality standards, there is also an emerging body of standards and even regulations that affect all levels of education, including continuous training.

For example the EU's European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) publishes the Standards and guidelines for quality assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG) [30]. One of its standards defines Student - centred learning, teaching and assessment

Standard:

Institutions should ensure that the programmes are delivered in a way that encourages students to take an active role in creating the learning process, and that the assessment of students reflects this approach.

Guidelines :

Student-centred learning and teaching plays an important role in stimulating students’ motivation, self-reflection and engagement in the learning process. This means careful consideration of the design and delivery of study programmes and the assessment of outcomes.

The implementation of student-centred learning and teaching

- respects and attends to the diversity of students and their needs, enabling flexible learning paths;

- considers and uses different modes of delivery, where appropriate;

- flexibly uses a variety of pedagogical methods;

- regularly evaluates and adjusts the modes of delivery and pedagogical methods;

- encourages a sense of autonomy in the learner, while ensuring adequate guidance and support from the teacher;

- promotes mutual respect within the learner-teacher relationship;

- has appropriate procedures for dealing with students’ complaints.

(ESG 2015: 12)[30]

Interestingly these guidelines do reflect a belief that learning should be flexible and diverse with respect to pedagogy, difficulty, place/times constraints, i.e. something that could in principle be implemented more easily through e-learning.

Standard 1.6 on learning resources and student support also implicitly supports the introduction of more digital learning.

Standard:

Institutions should have appropriate funding for learning and teaching activities and ensure that adequate and readily accessible learning resources and student support are provided.

Guidelines :

- For a good higher education experience, institutions provide a range of resources to assist student learning. These vary from physical resources such as libraries, study facilities and IT infrastructure to human support in the form of tutors, counsellors and other advisers. The role of support services is of particular importance in facilitating the mobility of students within and across higher education systems.

- The needs of a diverse student population (such as mature, part-time, employed and international students as well as students with disabilities), and the shift towards student-centred learning and flexible modes of learning and teaching, are taken into account when allocating, planning and providing the learning resources and student support.

(ESG 2015: 14)[30]

In sum, we could say that the EC advocates at least implicitly the introduction of e-learning elements in the curricula of higher education and requires that it should be flexible and include a comprehensive support structure.

Competences required from course designers and teachers

Qualifications of teachers and designers engaged in e-learning are often defined in a normative ways, e.g. through associations or study goals. There also exist empirical studies that analyse job interviews or expert's opinions on the subject. Finally there is a littérature on e-learning competence found with teachers, e.g. the TPACK model.

Domains of competence for educational technologists

Hartley, Kinshuk, Koper, Okamoto, & Spector, J. M. (2010) [31] identify thirteen curriculum/competence topic areas for educational technologists. These topic areas “were identified and clarified after discussions with various experts and practitioners, and the Working Committee’s perspective was that identifying curricula topics is equivalent to clustering competences into a closely related set of knowledge, skills and attitudes which enable a person to perform a task or fulfill a job function with consistency and proficiency.” (Hartley, 2000: 208) [31]:

- Introduction to Advanced Learning Technology (ALT);

- Introduction to Human Learning in Relation to New Technologies;

- Foundations, Developments and Evolution;

- Typologies and Key Approaches;

- User Perspectives;

- Learner Perspectives;

- Systems Perspectives;

- Social Perspectives;

- Design Requirements;

- Design Processes and the Development Lifecycle;

- Instructional Design;

- Evaluation Models and Practices; and

- Emerging Issues

Each of these include subtopics and more precise competence areas that we shall not reproduce here.

According to the AECT Handbook of Research (Spector et al., 2013) [32], Hartley et al (2010) [31] furthermore identified the following general rather abstract domains of competence:

1. Knowledge competence — includes those competences concerned with demonstrating knowledge and understanding of learning theories, of different types of advanced learning technologies, technology-based pedagogies, and associated research and development.

2. Process competence—focuses on skills in making effective use of tools and technologies to promote learning in the twenty-first century; a variety of tools ranging from those which support virtual learning environments to those which pertain to simulation and gaming are mentioned.

3. Application process—concerns the application of advanced learning technologies in practice and actual educational settings, including the full range of life-cycle issues from analysis and planning to implementation and evaluation.

4. Personal and social competence—emphasizes the need to support and develop social and collaboration skills while developing autonomous and independent learning skills vital to lifelong learning in the information age.

5. Innovative and creative competence—recognizes that technologies will continue to change and that there is a need to be flexible and creative in making effective use of new technologies; becoming effective change agents within the education system is an important competence domain for instructional technologists and information scientists.This second list's “perspective is that a competence is a set of related knowledge, skills and attitudes which enable a person to perform a task or fulfill a job function with consistency and proficiency” (Hartley et al., 2010:211)

Multimedia competences required from educational technologists

Albert D. Ritzhaupt et al. [33], based on prior work [34], conducted a study to identify multimedia competencies required for educational technologists. Although the study did focus on "multimedia", other items "came up".

After a literature review that was conducted “to examine types the types of knowledge, skills, and abilities recommended by the experts in the field (Alessi and Trollip 2001; Mayer 2001; Moallem 1995; Tennyson 2001; Kenny et al. 2005; Sumuer et al. 2006; Ritzhaupt et al. 2010; Sugar et al. 2009, 2012; Daniels et al. 2012; Wakefield et al. 2012)” (p.19), the authors analyzed 205 job announcements. This led to a list of 85 key multimedia competencies grouped into knowledge, skills and abilities. These competences then then were measured with the multimedia competency survey (ETMCS) addressed to educational technologists. Each item was rated with a five point scale: Not important at all (1); Important to a small extent (2); to some extent (3); to a moderate extent (4); and to a great extent (5).

For each knowlede, skills and abilities item set, exploratory factor analyses allowed to identify important underlying constructs. Below, we summarize these factors:

| Factor label | Rating mean | SD | % of variance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge: theories and methods of instruction have the highest ratings. Educational authoring and utility software, and programming and scripting languages have the lowest. However, in terms of variance explained, educational authoring and utility software comes first. | ||||

| 1. | Educational authoring and utility software | 2.90 | 0.89 | 39.265 |

| 2. | Graphics, web, audio and video software | 3.71 | 0.88 | 7.224 |

| 3. | Theories and methods of instruction | 3.89 | 0.78 | 5.777 |

| 4. | Programming and scripting languages | 3.02 | 0.95 | 4.033 |

| 5. | Office production software | 3.52 | 0.88 | 2.526 |

| 6. | Course management software | 3.85 | 0.90 | 2.455 |

| 7. | Accessibility and copyrights | 3.55 | 0.99 | 1.942 |

| 8. | Computer hardware and networks | 3.23 | 1.00 | 1.862 |

| Skills: Soft skills have the highest rating, and multimedia production skills the lowest. | ||||

| 1. | Multimedia production skills | 3.29 | 0.90 | 41.16 |

| 2. | Soft skills | 4.48 | 0.67 | 15.20 |

| 3. | Managerial and technical skills | 3.63 | 0.83 | 5.89 |

| 4. | Supporting skills | 3.81 | 0.85 | 5.09 |

| Abilities: The ability of a professional to Work in a team-oriented environment was rated highest. | ||||

| 1. | Work in a team-oriented environment | 4.54 | 0.70 | 46.94 |

| 2. | Conduct an instructional design process | 4.32 | 0.74 | 9.76 |

| 3. | Teaching, multitasking, and prioritization | 3.83 | 0.84 | 6.54 |

| 4. | Work with technology and assessment | 4.21 | 0.76 | 5.33 |

Competence required from teachers

A large literature on barriers to e-learning looks at teachers digital literacy (or eCompetence) skills.

Frameworks like TPACK insist that that teachers not only need technological knowledge (and of course Content and Pedagogical one), but that these dimensions also need to be integrated. In other words, it is not enough for a teacher to possess digital literacy, he/she also must be able to apply it to pedagogy and to contents and then integrated the three as in this model's name: technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)

Again, there is an older tradition of research in distance education, most of which represents a form of e-learning. According to Dooley et al. (2003:84) [35] “Cyrs (1997) [36] identified areas of competence important to distance education: course planning and organization, verbal and nonverbal presentation skills, collaborative teamwork, questioning strategies, subject matter expertise, involving students and coordinating their activities at field sites, knowledge of basic learning theory, knowledge of the distance learning field, design of study guides, graphic design, and visual thinking.”

Can creating appropriate e-learning courses be taught to non-specialists ?

Several authors argue that faculty development should be planned at several levels, e.g. the individual, the team and the institution and also in terms of embedded layers of competencies.

University professors

Schneckenberg (2010:986) [37] defines eCompetence as an action competence. In his study concludes: “A sustainable integration of eLearning into universities works more efficiently in integrative innovation management approaches, where faculty take over active roles and responsibilities for the implementation and use of ICT in teaching and learning and [...] the competence development of faculty relies in these participative approaches on a set of interrelated learning activities—like peer interaction and review, self- and group reflection, and the application of ICT tools to produce ePortfolios.”. He also adds (p 988) that “eCompetence is a specific action competence of faculty to master learning technologies. Its acquisition requires more than to respectively learn new knowledge, to develop new skills or to take on new attitudes. Action competence is a holistic concept which demands a holistic design of competence development measures.”

Training of other professionals

Sutton et al. (2005). [38] organized an introduction to creating e-learning modules for librarians, called e-FOLIO. They report that (a) an e-learning course where participants learn from ‘reflection on doing’ seems to contribute to a higher completion rate. and (b) course developers should consider the extra resilience of small groups over pairs.

Can e-learning literacy be taught ?

We believe that e-learning competence must be taught to every (futur) citizen, since it seems to overlap with competences required for "knowledge working". E-learning competence can be seen either as a list of attributes that individuals posses (e.g. attitudes, skills, behaviors, knowledge, personality traits) or simple as the ability to follow e-learning courses effectively.

E-learning literacy can be acquired through experience. Research shows that students with higher prior experience have higher continuency (e.g. Stoel and Lee (2003) [39] cited by Lin (2011) [23]). Generally speaking, the author ([23] also claims that user expertise of a product or system is positively related to the length of experience with that product or system and that user expertise tends to have a positive effect on user loyalty. However, while any e-learning experience does entail learning about e-learning, we cannot rely on it. Participant may fail, not learn enough, reach local optima (e.g. survive a program as opposed to thrive within), etc.

E-learning competence touches affective, cognitive and behavioural dimensions. Learning involves acquiring and modifying knowledge, skills, strategies, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Schunk: 2012 :2) [40]. If we consider that strategies are a king of skill and that beliefs are related to attitudes, we can narrow the list to knowledge, attitudes, skills and "knowing in action". Development of these dimensions takes time and must be integrated within the curricula, although some basic knowledge and know-how could be taught before enrolment.

Chia-Wen Tsai (2010)[41] found that students that were training in using e-learning competencies show better learning performance. “The results show that students who received online collaborative learning with initiation had higher grades than those without.” (idem, Abstract)

Content

Participants in e-learning activities should be aware of various constraints and opportunities as well as e-learning competences that are required and need to be developed. Some of this could be taught prior to enrolment in a program, e.g. in conjunction with a self-positioning test that makes a participant think about external constraints, requirements of the program and his/her existing competency.

Since "knowing about e-learning" is not the focus of the student's learning, contents probably should be made very short and well structured. Moreover, contents should be related to activities that allow developing attitudes, skills and behavior.

List of e-learning contents:

- (to do)

Attitudes

Attitudes

List of "general" e-learning attitudes:

- Openness with respect to new models of learning and teaching

- Curiosity to explore

- Willingness to respect other ways of "doing", e.g. using online communication tools

Skills development

Skills refer to the ability to do something and it is related to expertise.

Bates, 2005 states that we know a lot about skill development and summarized the following items

- skills development is relatively context-specific. In other words, these skills need to be embedded within a knowledge domain. For example, problem solving in medicine is different from problem-solving in business. Different processes and approaches are used to solve problems in these domains (for instance, medicine tends to be more deductive, business more intuitive; medicine is more risk averse, business is more likely to accept a solution that will contain a higher element of risk or uncertainty);

- learners need practice – often a good deal of practice – to reach mastery and consistency in a particular skill;

- skills are often best learned in relatively small steps, with steps increasing as mastery is approached;

- learners need feedback on a regular basis to learn skills quickly and effectively; immediate feedback is usually better than late feedback;

- although skills can be learned by trial and error without the intervention of a teacher, coach, or technology, skills development can be greatly enhanced with appropriate interventions, which means adopting appropriate teaching methods and technologies for skills development;

- although content can be transmitted equally effectively through a wide range of media, skills development is much more tied to specific teaching approaches and technologies.

- Bates (2015), 1.2 The skills needed in a digital age [19].

In sum, he argues that skills development requires a more active pedagogy that includes some sort of mastery approach, feedback and tutoring. Bates (section A.5.1) cites thinking activities (triggered by various activities), discussion, and practical activities as pedagogical strategies. Also, he points out that skills are context-specific and that skill (learning) goals must be carefully defined.

Schunk (2012:280ff.) [40] distinguishes between general and specific skills. “General skills apply to a wide variety of disciplines; specific skills are useful only in certain domains.” (p. 280). He cites Perking and Salomon (1989:17): “General knowledge includes widely applicable strategies for problem solving, inventive thinking, decision making, learning, and good mental management, sometimes called autocontrol, autoregulation, or metacognition. In chess, for example, very specific knowledge (often called local knowledge) includes the rules of the game as well as lore about how to handle innumerable specific situations, such as different openings and ways of achieving checkmate. Of intermediate generality are strategic concepts, like control of the center, that are somewhat specific to chess but that also invite far-reaching application by analogy.”. Skill acquisition, the author argues, is largely domain specific, requiring “a rich knowledge base that includes the facts, concepts, and principles of the domain, coupled with learning strategies that can be applied to different domains and that may have to be tailored to each domain.” (p. 281) and “findings imply that students need to be well grounded in basic content-area knowledge (Ohlsson, 1993), as well as in general problem-solving and self-regulatory strategies” (p.281).

List of specific e-learning skills:

- (to do)

List of higher level e-learning skills

Behavior sets

We distinguish between what people know and what they do. E.g. most participants in an e-learning course may have the skills to formulate a question in a forum, but that does not mean that they will do it. E-learning competency, from a behavioral perspective, is something that can be observed in a real context. Such "knowing in action" will require extra efforts from both the participants and the teachers.

Digital literacy statements and assessment tools

E-learning literacy statements

[... to be found ...]

Some institutions make digital literacy statements in an educational context (which does not cover the same semantic field). For example:

- Professionalism in the Digital Environment (PriDE) (a JISC project)

- “A digitally literate person in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science is critically and ethically aware, confident in engaging in a wide array of digital practices, resources/tools and academic and professional environments, and establishing coherent identities.” example definition from Professionalism in the Digital Environment (PriDE)

Example instruments (online)

A quick examination of online materials (below) shows that US and UK online institutions offer on their site a combination of checklists and online quizzes that allow interested persons to evaluate whether they should consider taking an online program or class.

- Student success (under the direction of Mark Brown)

- Is online learning for me? : Quiz on WashingtonOnline

- Are Online Courses for You?: iSeek education quiz (Minnesota)

- Minnesota State colleges & Universities quiz: Is Online Learning Right for Me? (checklits) and online education quiz. See also Is online learning right for you? (checklist)

- Kennebec VAlley Community College: Is Distance Education Right For Me Quiz

- Old Dominion university: Is Online Learning For Me?

- Grand Rapids Community College: Is Online Learning Right for Me? (checklist) and Interactive Self-Assessment for Online Learning pointing to Is distance learning right for me ? (Quiz, by Michigan colleges online). See also time management and Technology requirements

- University of Exeter: iTest (Quiz)

- Digital Literacies Toolkit ( University of Southampton ). Includes specific e-learning literacy tests.

Links

- General

- e-Learning and 21st century skills and competences, June 24, 2009 by Tony Bates .

- Preparing Students for Elearning, Blog post, elearnspace, 2002.

- Example pages addressing students

- Example pages addressing teachers

- What Technology and Skills Are Required for Blended Learning? (e-learning Ontario).

- Free Online courses

- Succeed with learning is a free course which lasts about 8 weeks, with approximately 3 hours' study time each week. Quote (07/2016) “This course takes your life as its starting point, developing your awareness of just how much you have already learned and what you are capable of. It will suggest ways of 'fine-tuning', and building on, the expertise you have developed in your life. You will also learn some interesting theories about how we learn, and some of the key skills and tools to make your learning a success.”

- Learning in a digital age planning page. A WikiEducator page that plans a course. Some good resources.

Bibliography

Cited

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Seongyoun Hong and Insung Jung (2011), The distance learner competencies: a three-phased empirical approach, Educational Technology Research and Development, February 2011, Volume 59, Issue 1, pp 21-42, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-010-9164-3

- ↑ Coggins, C. C. (1988). Preferred learning styles and their impact on completion of external degree programs. American Journal of Distance Education, 2(1), 25–37

- ↑ Dille, B., & Mezack, M. (1991). Identifying predictors of high risk among community college telecourse students. American Journal of Distance Education, 5(1), 24–35.

- ↑ Garrison, D. R. (1993). Dropout in adult education. In T. N. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of education (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon.

- ↑ Bernt, F. M., & Bugbee, A. C. (1993). Study practices and attitudes related to academic success in a distance learning programme. Distance Education, 14(1), 97–112.

- ↑ Golladay, R., Prybutok, V., & Huff, R. (2000). Critical success factors for the online learner. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 40(4), 69–71.

- ↑ Powell, G. C. (2000). Are you ready for WBT? Resource document. http://it.coe.uga.edu/itforum/paper39/ paper39.html. Accessed October 1, 2009.

- ↑ Li, H. (2002). Distance education: Pros, cons, and the future. WSCA annual conference. http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/19/cd/dc.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2009.

- ↑ Schrum, L., & Hong, S. (2002). Dimension and strategies for online success: Voices from experienced educators. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 57–67.

- ↑ Li‐An Ho, Tsung‐Hsien Kuo, Binshan Lin, (2010) "Influence of online learning skills in cyberspace", Internet Research, Vol. 20 Iss: 1, pp.55 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10662241011020833

- ↑ Watkins, R. (2005), “Preparing e‐learners for online success”, available at: http://www.astd.org/LC/2005/0905_watkins.htm (accessed 10 June 2009).

- ↑ Birch, D. (2001), “E‐learner competencies”, available at: http://brightways.net/Articles/wp01_elc.pdf (accessed 21 June 2009).

- ↑ Stary, C., & Weichhart, G. (2012). An e-learning approach to informed problem solving. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal (KM&EL), 4(2), 195-216. http://www.kmel-journal.org/ojs/index.php/online-publication/article/viewArticle/184

- ↑ Shirley Alexander (2001), E‐learning developments and experiences, Education + Training 2001 43:4/5 , 240-248

- ↑ Weller M.J. and Mason, R.D. (2000), “Evaluating an open university Web course: issues and innovations”, in Asensio, M., Foster, J., Hodgson, V. and McConnell, D. (Eds), Proceedings of Networked Learning 2000, Lancaster, April, available: http://www‐tec.open. ac.uk/tel/people/weller/martin/lancs.html

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Daniel, Sir John (2016), Making Sense Of Blended Learning: Treasuring An Older Tradition Or Finding A Better Future?, Contact North, Retrieved from http://empower.eadtu.eu/images/making_sense_of_blended_learning-eng.pdf

- ↑ Paechter, M., Maier, B., & Macher, D. (2010). Students’ expectations of, and experiences in e-learning: Their relation to learning achievements and course satisfaction. Computers & education, 54(1), 222-229.

- ↑ Sun, P. C., Tsai, R. J., Finger, G., Chen, Y. Y., & Yeh, D. (2008). What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction. Computers & education, 50(4), 1183-1202.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning, BCcampus. http://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage

- ↑ Jara, M., & Mohamad, F. (2007). Pedagogical templates for e-learning, London Knowledge Lab, Institute of Education. http://eprints.ioe.ac.uk/960/1/Jara2007Pedagogical.pdf

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 JISC (2014), Developing digital literacies. Provides ideas and resources to inspire the strategic development of digital literacies - those capabilities which support living, learning and working in a digital society. Online, Retrieved May 26 2016 from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-digital-literacies and https://www.jisc.ac.uk/full-guide/developing-digital-literacies (print version)

- ↑ Tzu-Bin Lin, Jen-Yi Li, Feng Deng, & Ling Lee. (2013). Understanding New Media Literacy: An Explorative Theoretical Framework. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(4), 160–170. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.16.4.160

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Kan-Min Lin, e-Learning continuance intention: Moderating effects of user e-learning experience, Computers & Education, Volume 56, Issue 2, February 2011, Pages 515-526, ISSN 0360-1315, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.09.017. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131510002800)

- ↑ Bereiter, C. and Scardamalia, M. 2003. “Learning to work creatively with knowledge”. In Powerful learning environments: Unravelling basic components and dimensions, Edited by: De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., Entwistle, N. and van Merriënboer, J. 55–68. Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd.

- ↑ Terje Väljataga , Mart Laanpere (2010), Learner control and personal learning environment: a challenge for instructional design, Interactive Learning Environments, Vol. 18, Iss. 3, 2010

- ↑ Klein, Davina C. D.; Harold F. O’Neil, Jr. and Eva L. Baker, A Cognitive Demands Analysis of Innovative Technologies, CSE Technical Report 454, National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST)/UCLA, PDF (Retrieved March 2016).

- ↑ Frydenberg J (2002) Quality standards in e-learning: A matrix of analyses. The International Review Research in Open and Distance Learning 3(2).

- ↑ Ossiannilsson, Ebba; Williams, Keith; Camilleri, Anthony F.; Brown, Mark: Quality models in online and open education around the globe. State of the art and recommendations. Oslo : International Council for Open and Distance Education 2015, 52 S. - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-108795, Retrieved from http://www.pedocs.de/frontdoor.php?source_opus=10879

- ↑ EiFel (2004), eLEARNER BILL OF RIGHTS, Broken (typical EU) link: http://www.education-observatories.net/seeque, Retrieved May 31 2016 from http://www.eife-l.org/competencies/billofrights

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 ENQA (2015), Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG), retrieved May 30 2015 from http://www.enqa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ESG_2015.pdf

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Hartley, R., Kinshuk, Koper, R., Okamoto, T., & Spector, J. M. (2010). The education and training of learning technologists: A competences approach. Educational Technology & Society, 13 (2), 206–216.

- ↑ Spector J. Michael, M. David Merrill, Jan Elen & M. J. Bishop (eds.) (2013) Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, Springer, ISBN 1461431840

- ↑ Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Martin, F. (2014). Development and validation of the educational technologist multimedia competency survey. Educational Technology Research and Development, 62(1), 13-33.

- ↑ Ritzhaupt, Albert, Florence Martin, and Katharine Daniels. "Multimedia competencies for an educational technologist: A survey of professionals and job announcement analysis." Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 19.4 (2010): 421-449.

- ↑ Dooley, K. E., Lindner, J. R., & Richards, L. J. (2003). A comparison of distance education competencies delivered synchronously and asynchronously. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(1), 84-94.

- ↑ Cyrs, T. (1997). Teaching at a distance with the merging technologies: An instructional systems approach. Las Cruces, NM: Center for Educational Development.

- ↑ Schneckenberg, Dirk. "Overcoming barriers for eLearning in universities—portfolio models for eCompetence development of faculty." British Journal of Educational Technology 41.6 (2010): 979-991.

- ↑ Sutton, A., Booth, A., Ayiku, L. and O’Rourke, A. (2005), e-FOLIO: using e-learning to learn about e-learning. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 22: 84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-3327.2005.00606.x, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1470-3327.2005.00606.x/full

- ↑ L. Stoel, K.H. Lee, Modeling the effect of experience on student acceptance of Web-based courseware, Internet Research, 13 (5) (2003), pp. 364–374

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Dale H. Schunk. (2012). Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective, 6th edition, Pearson: Boston, MA, 2012. pp . ISBN, 079-0137071951

- ↑ Chia-Wen Tsai. 2010. Do students need teacher's initiation in online collaborative learning?. Comput. Educ. 54, 4 (May 2010), 1137-1144. DOI=http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.021

Other

- Badrul H. Khan and Mohamed Ally, International Handbook of E-Learning Volume 1: Theoretical Perspectives and Research, Routledge International, ar 24, 2015

- Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning, BCcampus. http://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage

- Belshaw, Doug (2011). What is 'digital literacy'? Ed.D thesis, Department of Education at Durham University Word, PDF

- Bullen, M., Morgan, T. & Qayyum, A. (2011). Digital Learners in Higher Education: Generation is not the issue. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, Vol. 37(1). http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/550/298

- Dooley, K. E., Lindner, J. R., & Richards, L. J. (2003). A comparison of distance education competencies delivered synchronously and asynchronously. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(1), 84-94.

- Gabriel, M. A., Campbell, B., Weibe, S., MacDonald, R. J. & McAuley, A. (2011). The Role of Digital Technologies in Learning Expectations of First-Year University Students. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology, Vol. 38(1) http://www.cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/637/335

- Oliver, Ron, and Jan Herrington. Teaching and learning online: A beginner's guide to e-learning and e-teaching in higher education. Edith Cowan University. Centre for Research in Information Technology and Communications, 2001.

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R. & Baki, M. (2013) The Effectiveness of Online and Blended Learning: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature, Teachers College Record Vol. 115, 030303. http://www.sri.com/sites/default/files/publications/effectiveness_of_online_and_blended_learning.pdf

- Ossiannilsson, Ebba; Williams, Keith; Camilleri, Anthony F.; Brown, Mark: Quality models in online and open education around the globe. State of the art and recommendations. Oslo : International Council for Open and Distance Education 2015, 52 S. - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-108795, Retrieved from http://www.pedocs.de/frontdoor.php?source_opus=10879

- Piskurich, G. M. (Ed.). (2004). Preparing learners for e-learning. John Wiley & Sons.

- Uvalić-Trumbić, S & Daniel, J. S. (eds.) (2013). A Guide to Quality in Online Learning, by Neil Butcher & Merridy Wilson-Strydom,

- Wong, A. L. S. (2015). What are the experts’ views of the barriers to e-learning diffusion in Hong Kong. International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, Vol. 7(2) pp. 25-51

- The Conference Board of Canada (2014) Employability Skills 2000+ Ottawa ON: Conference Board of Canada

- Fallow, S. and Stevens, C. (2000) Integrating Key Skills in Higher Education: Employability, Transferable Skills and Learning for Life London UK/Sterling VA: Kogan Page/Stylus

- Fischer, K.W. (1980) A Theory of Cognitive Development: The Control and Construction of Hierarchies of Skills Psychological Review, Vol. 84, No. 6

- Williams, P.E. (2003). Roles and competencies for distance education programs in higher education institutions. The American Journal of Distance Education, 17 (1), 45-57. (2003)