Digital literacy

Introduction

Digital literacy is the “ability to access, process, understand and create information or media content in the digital environment” (Hsieh, 2012). [1]).

In 2016, Wikipedia defined Digital literacy as the knowledge, skills, and behaviors used in a broad range of digital devices such as smartphones, tablets, laptops and desktop PCs, all of which are seen as network rather than computing devices. In other words, this definition somehow extends computer literacy by networking aspects, but further down, digital literacy is rather defined in terms of applicable competencies, including social ones: “A digitally literate person will possess a range of digital skills, knowledge of the basic principles of computing devices, skills in using computer networks, an ability to engage in online communities and social networks while adhering to behavioral protocols, be able to find, capture and evaluate information, an understanding of the societal issues raised by digital technologies (such as big data), and possess critical thinking skills.”

In 2011, Wikipedia defined Digital literacy as “the ability to locate, organize, understand, evaluate, and analyze information using digital technology. It involves a working knowledge of current high-technology, and an understanding of how it can be used. Further, digital literacy involves a consciousness of the technological forces that affect culture and human behavior. Digitally literate people can communicate and work more efficiently, especially with those who possess the same knowledge and skills. Research around digital literacy is concerned with wider aspects associated with learning how to effectively find, use, summarize, evaluate, create, and communicate information while using digital technologies, not just being literate at using a computer. Digital literacy encompasses all digital devices, such as computer hardware, software (particularly those used most frequently by businesses), the Internet, and cell phones. A person using these skills to interact with society may be called a digital citizen.” (retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET))

See also:

Subpages (scales):

Component models and definitions of digital literacy

It is very difficult to give a precise definition of digital literacy and it is probably safer to speak about various digital literacies. “digital literacy” can be understood as “a shorthand for the myriad social practices and conceptions of engaging in meaning making mediated by texts that are produced, received, distributed, exchanged, etc., via digital codification.” (Lankshear and Knobel, nd) [2]

Often, digital literacies are associated with "new literacies". For example, Lankshera and Knobel (2013).[3] adopted the idea that “new literacies” was best understood in terms of practices that were increasingly mediated by new technologies, but not necessarily mediated by new technologies.

Wikipedia (April 2016), also states that digital literacy is a new literacy, and may itself be decomposed into several sub-literacies. One such decomposition considers digital literacy as embracing computer literacy, network literacy, information literacy and social media literacy. And in the new literacies article (April 2016), we can read that “Accompanying the varying conceptualizations of new literacies, there are a range of terms used by different researchers when referring to new literacies, including 21st century literacies, internet literacies, digital literacies, new media literacies, multiliteracies, information literacy, ICT literacies, and computer literacy.”

Technical components of new literacies are according to Wikipedia (April 2016): practices as instant messaging, blogging, maintaining a website, participating in online social networking spaces, creating and sharing music videos, podcasting and videocasting, photoshopping images and photo sharing, emailing, shopping online, digital storytelling, participating in online discussion lists, emailing and using online chat, conducting and collating online searches, reading, writing and commenting on fan fiction, processing and evaluating online information, creating and sharing digital mashups, etc. (see: Black, 2008; Coiro, 2003; Gee, 2007; Jenkins, 2006; Kist, 2007; Lankshear & Knobel, 2006; Lessig, 2005; Leu, et al. 2004; Prensky, 2006).

According to Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear & Leu, (2008) [4] most new literacies perspectives share four assumptions. New literacies:

- include the new skills, strategies, dispositions, and social practices that are required by new technologies for information and communication;

- are central to full participation in a global community;

- regularly change as their defining technologies change; and

- are multifaceted and our understanding of them benefits from multiple points of view.

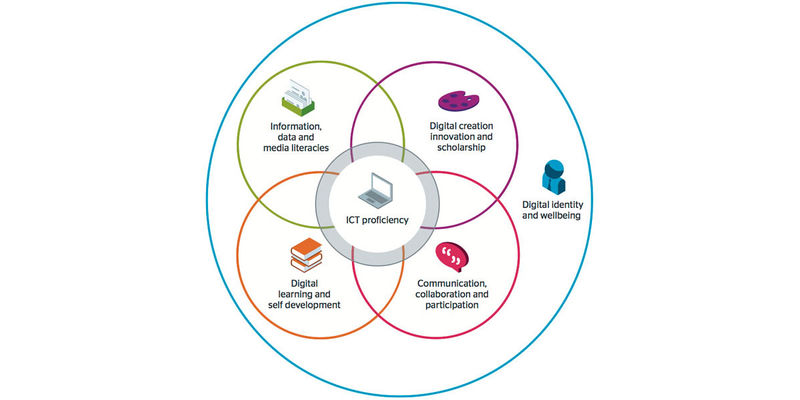

The JISC model

The JISC Developing digital literacies [5] guide defines digital literacies as “those capabilities which fit an individual for living, learning and working in a digital society”. Furthermore, this report distinguishes between seven types of digital literacies:

Belshaw (2001) [6] who's work is related to the JISC model, identifies eight essential overlapping elements of digital literacies and which further propagate the idea that "digital literacy" is a rather complex assembly of various skills needed to perform in a given type of (digital) society.

- Cultural: understanding the contexts and their norms (e.g. acceptable behavior on Facebook is not the same as in an LMS)

- Cognitive: ability to use a set of cognitive tools

- Constructive: being able to construct something new (including using and remixing)

- Communicative: understanding how communications media work, including network literacy

- Confident: understand that digital literacies are mutable, open to experimentation

- Creative: willingness to take risks, to do new things in new ways.

- Critical: being able to reflect upon literacy practices in various semiotic domains

- Civic: ability for the literacy practices resulting from new technologies and tools to support the development of Civil Society.

DigComp

In Europe, the most comprehensive framework is the Digital Competence Framework [7], also known as DigComp (Vuorikari et al. 2016) [8]. It defines digital competences in five areas that are summarized in the The Digital Competence Framework 2.0 web page (retrieved May 10, 2019, reused with permission)

1) Information and data literacy: To articulate information needs, to locate and retrieve digital data, information and content. To judge the relevance of the source and its content. To store, manage, and organise digital data, information and content.

2) Communication and collaboration: To interact, communicate and collaborate through digital technologies while being aware of cultural and generational diversity. To participate in society through public and private digital services and participatory citizenship. To manage one’s digital identity and reputation.

3) Digital content creation: To create and edit digital content To improve and integrate information and content into an existing body of knowledge while understanding how copyright and licences are to be applied. To know how to give understandable instructions for a computer system.

4) Safety: To protect devices, content, personal data and privacy in digital environments. To protect physical and psychological health, and to be aware of digital technologies for social well-being and social inclusion. To be aware of the environmental impact of digital technologies and their use.

5) Problem solving: To identify needs and problems, and to resolve conceptual problems and problem situations in digital environments. To use digital tools to innovate processes and products. To keep up-to-date with the digital evolution.

These areas include 21 competencies and defined at eight proficiency levels (i.e. measurable learning outcomes). For example, the problem solving area is divided into solving technical problems, identifying needs and technological responses, creatively using digital technologies, and identifying digital competence gaps.

“Eight proficiency levels for each competence have been defined through learning out-comes (using action verbs, following Bloom’s taxonomy) and inspired by the structure and vocabulary of the European Qualification Framework (EQF). Moreover, each level description contains knowledge, skills and attitudes, described in one single descriptor for each level of each competence; this equals to 168 descriptors (8 x 21 learning out-comes).” (Carretero et al., 2017) [7]

| Levels in DigComp 1.0 | Levels in DigComp 2.1 | Complexity of tasks | Autonomy | Cognitive domain |

|

Foundation |

1 | Simple tasks | With guidance | Remembering |

| 2 | Simple tasks | Autonomy and with guidance where needed | Remembering | |

|

Intermediate |

3 |

Well-defined and routine tasks, and straightforward problems | On my own | Understanding |

|

4 |

Tasks, and well-defined and non-routine problems | Independent and according to my needs | Understanding | |

|

Advanced |

5 |

Different tasks and problems | Guiding others | Applying |

|

6 |

Most appropriate tasks | Able to adapt to others in a complex context | Evaluating | |

|

Highly specialised |

7 |

Resolve complex problems with limited solutions | Integrate to contribute to the professional practice and to guide others | Creating |

|

8 |

Resolve complex problems with many interacting factors | Propose new ideas and processes to the field | Creating |

The ProjectDQ Model

Yuhyun Park, for the world economic forum, identifies 8 digital life skills all children need – and a plan for teaching them that we quote below:

- Digital citizen identity: the ability to build and manage a healthy identity online and offline with integrity

- Screen time management: the ability to manage one’s screen time, multitasking, and one’s engagement in online games and social media with self-control

- Cyberbullying management: the ability to detect situations of cyberbullying and handle them wisely

- Cybersecurity management: the ability to protect one’s data by creating strong passwords and to manage various cyberattacks

- Privacy management: the ability to handle with discretion all personal information shared online to protect one’s and others’ privacy

- Critical thinking: the ability to distinguish between true and false information, good and harmful content, and trustworthy and questionable contacts online

- Digital footprints: The ability to understand the nature of digital footprints and their real-life consequences and to manage them responsibly

- Digital empathy: the ability to show empathy towards one’s own and others’ needs and feelings online

Training opportunities and guides based on that model are available through the ProjectDQ Website.

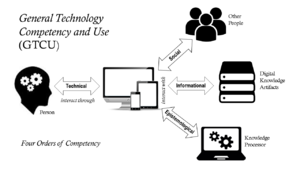

General Technology Competency and Use (GTCU) Framework

Desjardins (2001)[9] defines three basic functions of digital technology.

- Interact with other users (Communicational Use: transmit/receive)

- Interact with documents (Informational Use: store/ retrieve)

- Assign and interact with processes (Computational Use: process programs or data)

These functions require four orders of competences to be used effectively in educational contexts outlined in the General Technology Competency and Use (GTCU) Framework

The first order concerns technical manipulation skills.

- Technical Order of Competency: includes uses and interactions with the technological object regardless of intent (language, commands, etc,)

The remaining three are dimensions to be used to survey competences related to the intended outcomes of the uses.

- Social Order of Competency: includes all strategies and reflections in technology mediated communication and interaction with others

- Informational Order of Competency: includes theoretical and practical knowledge in gathering, selecting, organizing and interpreting information

- Epistemological Order of Competency: includes usesof discipline and domain specific knowledge applied to digital tools for information processing tasks to identify and solve specific problems or complete specific tasks.

These four orders have been used to create a validated self-report instrument, Digital Competency Profiler[10], to profile the digital competences of university teachers and students.

Most important digital literacy components

Some of these are strongly overlapping among themselves, some only partly related to digital literacy but are being related.

- Computer literacy. Be able to use computers and related devices as well as various software.

- Network literacy. Be able to use computer networks (get it working and making use of it). According to Wikipedia, Network literacy is an emerging digital literacy that deals with computer network knowledge and skills. It is linked to computer literacy and information literacy.

- Informatics literacy. Be able to write computer programs and understand principles behind computation

- On-line reading literacy, also called online research comprehension: Be able to solve an inquiry problem. “At least five processing practices occur during online research and comprehension: (1) reading to identify important questions, (2) reading to locate information,(3) reading to evaluate information critically, (4) reading to synthesize information, and (5) reading to communicate information. Within these five practices reside the skills, strategies, and dispositions that are distinctive to online reading comprehension as well as to others that are also important for offline reading comprehension (Leu, Reinking, et al., 2007) [11]” cited by Wikipedia [12]

- Media literacy: repertoire of competencies that enable people to analyze, evaluate, and create messages in a wide variety of media modes, genres, and formats (Wikipedia)

- New media literacy: is a concept close to digital literacy.

- Web literacy: “comprises the skills and competencies needed for reading, writing and participating on the web.[1] It has been described as "both content and activity" - web users should not just learn about the web but also how to make their own website.[2] Web Literacy is closely related to Digital Literacy, Information Literacy, and Network literacy but differs in taking a more holistic approach.” (Wikipedia, April 2016).

- Communication and collaboration literacy, very closely related to some "networking" components of digital literacies and social literacy.

- Social literacy: a range of social skills, in particular: social perception, social cognition and social performance. [13]

- Social media literacy:

- Information literacy: ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively needed information.

- Information and Media literacy: Combines media and information literacy under a same umbrella.

- Scientifc literacy: Explaining phenomena scientifically, Evaluating and designing scientific enquiry, Interpreting data and evidence scientific ally ([PISA] [14]

- cultural competence: Being able to interact effectively in different cultural contexts.

Implications from the component models

Component model imply that there exist different profiles where some persons possess higher skills in some areas than in others. This can be explained by "normal" statistical spread of interests. However, systematic lack of skills in similar domains also may hint that a person does not feel to be competent to learn and does not show enough resilience to learn.

We can hypothesize that perceived ability to learn in general and with respect to a given domain may hinder learning. E.g. in a study by Scott and Ghinea (2014) [15], it was shown that “Students with growth beliefs tend to continue to practice when they encounter difficulty. Those with fixed beliefs do not. Thus, it is important that educators inspire growth beliefs, as ongoing practice is important for developing expertise [16], [17]. However, mindset may not reflect a single general construct focused on intelligence. This study shows some evidence that students may develop domain-specific beliefs in the area of computer programming.”. In addition, this study shows, that the mindset for programming aptitude may have a stronger relationship with programming practice than their mindset about their general intelligence.

Their research is based on Dweck and colleagues's research on mindsets, defined as “implicit theories about the malleability of human characteristics” (Yeager & Dweck, 2012 ) [18], and their impact on academic and social resiliance. Dweck et al, 1995 [19], review research that shows that “when people believe that attributes (such as intelligence or moral character) are fixed, trait-like entities (an entity theory), they tend to understand outcomes and actions in terms of these fixed traits ("I failed the test because I am dumb" or "He stole the bread because he is dishonest"). In contrast, when people believe that attributes are more dynamic, malleable, and developable (an incremental theory), they tend to focus less on broad traits and, instead, tend to understand outcomes and actions in terms of more specific behavioral or psychological mediators ("I failed the test because of my effort or strategy" or "He stole the bread because he was desperate").”. These two different frameworks trigger either helpless or mastery-oriented reactions as responses to individual setbacks. “The helpless pattern [...] is characterized by an avoidance of challenge and a deterioration of performance in the face of obstacles. The mastery-oriented pattern, in contrast, involves the seeking of challenging tasks and the maintenance of effective striving under failure.” (Dweck and Legget, 1988) [20]

As a conclusion, in an educational context, it may not be enough to identify "underdeveloped" components, it also must be understood how they related to individual differences, such as the perception of being able to learning technical "stuff". Learners seem to be more or less resiliant and this resiliance can be explained by both environmental factors and mindsets. With respect to outcomes, the authors then argue that they depend on both the presence of social and academic adversity and the person's interpretations of those adversities. [18]

Developmental and process models

Other models rather try to capture the abstract dimensions and the dynamics of digital literacy.

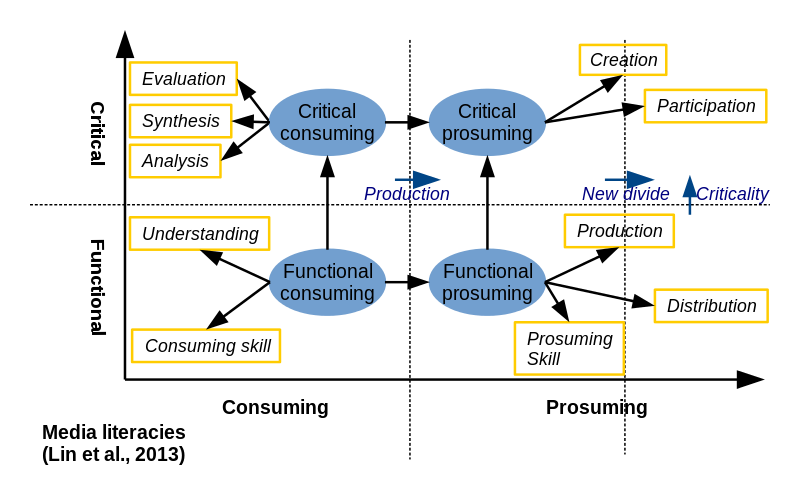

Lin et al. model

Lin et al. (2013) [21] present a two-dimensional framework consisting of functional consuming vs. critical consuming, and functional prosuming vs. critical prosuming literacies.

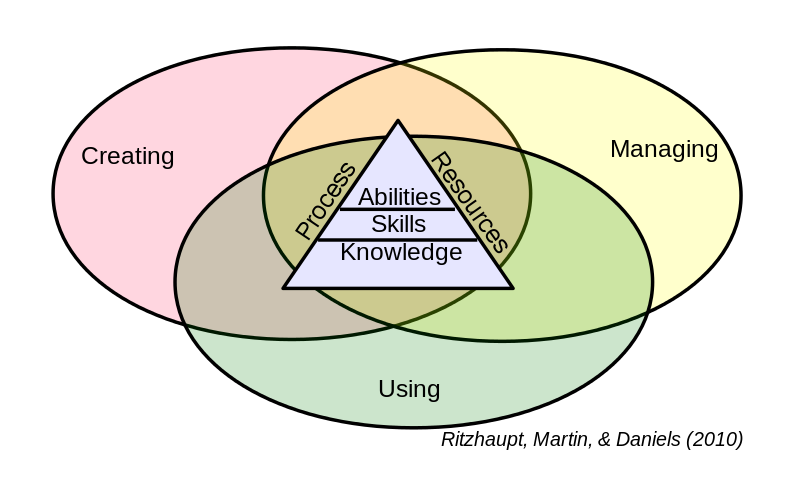

Ritzhaupt et al. multimedia competencies

Albert D. Ritzhaupt et al. [22] [23] conducted studies to identify the multimedia competencies of an educational technologist by creating a valid and reliable survey instrument to administer to educational technology professionals. In this context they presented a model of multimedia competency that is based on a definition of what educational technology is: “Educational technology is the study and ethical practice of facilitating learning and improving performance by creating, using, and managing appropriate technological processes and resources (Januszewski and Molenda 2007, p. 1)[24].”.

From this figure, one can then define competences as various knowledge, skills and abilities that enable to perform a given class of activities. Other authors would add attitudes and observed behaviors. Ritzhaupt (2014:15) cite Richey et al. (2001) [26] who “define competency as ‘‘a knowledge, skill or attitude that enables one to effectively perform the activities of a given occupation or function to the standards expected in employment’’ (p. 31).”

We argue that using, creating and managing various knowledge, skills and abilities is a definition that can be extended to any sort of digital literacy. The authors define knowledge as an organized body of usually factual or procedural information. Skills refer to the manual, verbal or mental manipulation know how. Abilities are capacities to perform an activity. The pyramid reflects that the idea that abilities rely on skills which in turn rely on knowledge. Using, creating and managing refers to different types of digital media activities. Implicitly, this model somewhat suggest a learning hierarchy that can be found in models like Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives

Teaching and learning digital literacy

“Beetham and Sharpe’s framework (2010) describes digital literacy as a development process from access and functional skills to higher level capabilities and identity. However, this will change depending on the context so it also reflects how individuals can be motivated to develop new skills and practices in different situations.” (JISC report [27])

The Beetham and Sharpe ‘pyramid model’ of digital literacy development model (2010) is a four-stage model:

- 4. Identity (I am...)

- 3. Practices (I do...)

- 2. Skills (I can ...)

- 1. Access and awareness (I have ....)

Starting from earlier definition of digital literacy ("as the capabilities which fit someone for living, learning and working in a digital society"), the authors of anonther JSIC guide on Developing students' digital literacy [28] define six elements for consideration that adapt the their general component model of digital literacy (see above) to the context of a short guide for education.

Digital literacy education statements/goals

Some institutions explicitly try to define learning outcomes that should be achieved at the end of a study program, e.g. see the KnowIT goals below.

The JISC digital literacy framework (retrieved April 2016), is used in several institutions:

- digital literacy statements from the PRIDE project

- Learning Literacies Framework from the Digidol project at Cardiff University.

The KnowIt Goals

The University of Colorado at Boulder defines ICT skills with a list of goals that describes what students should be able to achieve with IT.

- GOAL 1: Students will be able to recognize, articulate, and characterize what they need to know as they approach a problem, project, writing assignment or other research task.

- GOAL 2: Students will be able to access needed information effectively and efficiently independent of form or format.

- GOAL 3: Students will be able to evaluate information and information sources critically.

- GOAL 4: Students will be able to use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose as well as to retain selected information as part of their accumulated knowledge.

- GOAL 5: Students will be able to manage and organize information effectively and efficiently using information technologies.

- GOAL 6: Students will be able to produce and create structured electronic documents that successfully express their ideas for a specific audience and situation.

- GOAL 7: Students will be able to manipulate and use qualitative and quantitative data and aural and visual information using information technologies.

- GOAL 8: Students will be able to collaborate appropriately and effectively using information technologies.

- GOAL 9: Students will be able to successfully communicate produced content using information technologies.

- GOAL 10: Students will be able to participate as informed members of the academy who understand major legal, economic, social, ethical, privacy, and security issues related to information technologies.

Although these goals are then further expanded on the web site, there are no precise definitions of technical skills to be acquired. For example Goal 7 (data analysis skills) are defined as:

- Recognize when qualitative and/or quantitative data is needed.

- Select the appropriate application to manipulate data (ex. spreadsheets, statistical packages).

- Navigate and use applications effectively.

- Evaluate derived data using application effectively.

- Generate reports as appropriate.

- Recognize when visual and aural information is needed.

- Obtain, manipulate and insert visual and aural information (download, upload, change format, resize, crop, etc.) into personal documents using selected applications.

- Understand use of images and use appropriately in produced information.

In other words, this kind of list rather reflects the kind of technical knowledge that a student should seek out.

Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education

The American Association of College and Research libraries (ACRL), defined in 2000 five Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education standards that are operationalized with performance indicators and outcomes (7 pages). Below we reproduce the five top-level standards.

(1) The information literate student determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

(2) The information literate student accesses needed information effectively and efficiently.

(3) The information literate student evaluates information and its sources critically and incorporates selected information into his or her knowledge base and value system.

(4) The information literate student, individually or as a member of a group, uses information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.

(5) The information literate student understands many of the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information and accesses and uses information ethically and legally.(Standards, Performance Indicators, and Outcomes)[29]

These standards focus on the use of information, e.g. can identify needs, potential sources of information, find and access information, evaluate and synthesize information, integrate information with prior knowledge and use it for a purpose, and understand legal and social issues.

The 2015/2016 Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education [30] defines a more general, but also more abstract model. It is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Quotations and quotation boxes below are extracted from this text.

This 2016 framework grew “out of a belief that information literacy as an educational reform movement will realize its potential only through a richer, more complex set of core ideas.” (Introduction). The framework is informed by Wiggins and McTighe's work [31] on curricula arguing that one should focus on "big ideas" and "core tasks", as well as threshold concepts (Meyer, Land & Baillie, 2010) [32] identified for information literacy [33] [34] [35].

Six central concepts that anchor the frames (or threshold concepts) that must be learned:

- Authority Is Constructed and Contextual

- Information Creation as a Process

- Information Has Value

- Research as Inquiry

- Scholarship as Conversation

- Searching as Strategic Exploration

Each frame is described and then associated with a set of knowledge practices (i.e. observable abilities) and dispositions (defined as “tendency to act or think in a particular way” or as clusters “of preferences, attitudes, and intentions, as well as a set of capabilities that allow the preferences to become realized in a particular way”. [36]. Furthermore, as the frames hint, information literacy now also includes 'metaliteracy defined by Mackey and Jacobson (2011) [37]. Metaliteracy “expands the the scope of traditional information skills (determine, access, locate, understand, produce, and use information) to include the collaborative production and sharing of information in participatory digital environments (collaborate, produce, and share).”

We reproduced the entire frame set of the Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education.

The Big6 Guide

Developed by Michael B. Eisenberg and Robert Berkowith in 1987 (?) [38], the Big6 skills model (retrieved May 2016) includes six stages defining an information problem-solving model that is applicable whenever people need and use information. It should “help students develop the skills and understandings they need to find, process, and use information effectively”.

According to the about page, “the Big6 is a process model of how people of all ages solve an information problem. From practice and study, we found that successful information problem-solving encompasses six stages with two sub-stages under each”.

- 1 - Task definition

- 1.1 Define the information problem

- 1.2 Identify information needed

- 2 - Information Seeking strategies

- 2.1 Determine all possible sources

- 2.2 Select the best sources

- 3 - Location and Access

- 3.1 Locate sources (intellectually and physically)

- 3.2 Find information within sources

- 4 - Use of Information

- 4.1 Engage (e.g., read, hear, view, touch)

- 4.2 Extract relevant information

- 5 - Synthesis

- 5.1 Organize from multiple sources

- 5.2 Present the information

- 6 -Evaluation

- 6.1 Judge the product (effectiveness)

- 6.2 Judge the process (efficiency)

The stages do not necessarily need to be addressed in linear order or in depth. The authors just claim that each stages should be addressed.

This model also has been declined as Information, Communications, and Technology (ICT) Skills for Information Problem Solving curriculum, i.e. it relates information literacy skills to corresponding technical proficiency. [39]

Based on this model, a number of teaching materials for schools have been developed. Some are available commercially, others are free. Some of these materials show how to make use of technology.

Swiss Standards for Information Literacy

The Swiss E-lib.ch project "Information Literacy at Swiss Universities" created the Swiss Standards for Information Literacy. It is based on UNESCO's definition: “Information Literacy is the capacity of people to: Recognize their information needs; locate and evaluate the quality of information; store and retrieve information; make effective and ethical use of information; and apply information to create and communicate knowledge. (Catts & Lau 2008)”. (cited by Swiss Standards for Information Literacy) and also on ACRL 2000 [29].

The document defining the standard is published under a creative commons licence and includes definitions for six standards. For each, 3-4 learning outcomes are defined with three levels of performance (beginner, advanced and expert) are defined. Below we reproduce the definition of the six standards.

- Standard One - Need

- The information literate person recognises the need for information and determines the nature and extent of the information needed.

- defines and articulates the information need referring to a defined purpose

- understands the purpose, scope, and appropriateness of a variety of information sources

- selects and uses diverse sources of information to inform decisions

- Standard Two - Retrieval

- The information literate person finds needed information effectively and efficiently

- selects efficient methods or tools for finding information

- constructs and implements effective search strategies

- obtains information using appropriate methods

- Standard Three - Assessment

- The information literate person critically evaluates information and the information seeking process

- defines and applies criteria for evaluating information

- assesses the usefulness of the information obtained

- re-evaluates the nature and extent of the information need

- reflects on the information seeking process and revises search strategies as necessary

- Standard Four - Organisation

- The information literate person manages and shares information collected or generated

- records information selected and its sources

- organises, classifies, and stores information using appropriate methods

- shares information with others

- keeps up to date with information sources, information technologies, and investigative methods

- Standard Five - Application

- The information literate person applies prior and new information to accomplish a specific purpose

- applies new and prior information to the creation of new knowledge or a particular product

- communicates the new knowledge or product effectively to others

- revises the creation and communication process of knowledge or product

- Standard Six - Responsibility

- The information literate person acts as a responsible member of the information society

- acknowledges cultural, ethical, and socioeconomic issues related to the use of information

- conforms with conventions and etiquette related to the use of information

- legally obtains, stores, and disseminates all kinds of information

- Swiss Information Literacy Standards - informationskompetenz (retrieved May 26, 2016).

Teacher education

Engen et al (2015:18)[40]) in a study of Norway's system conclude: “To sum up, we see that digital competence in the curriculum does not correspond with formal documents that form the premises for teacher education. Weak links between the curriculum and guidelines for teacher education imply that teacher education does not meet the needs of school.”. In particular, the study found that:

- digital competences fade from the "central" well-written whitepaper to the guidelines

- premisses for digital competence in teacher education are somewhat fragmented and random

- subject integration is not consistent, i.e. similarities and disparities vary according to the subject.

The authors also notice that the “the curriculum is clear and takes a coherent, holistic approach to the use of digital tools and the development of digital skills, including digital judgement.” In other words, the main problem seems to be teacher education.

As of 2018m we can hypothesize that the situation is very similar in most other countries.

Digital literacy of the younger generation

Selwyn (2009:Abstract) “provides a comprehensive review of the recent published literatures on young people and digital technology in information sciences, education studies and media/communication studies. The findings show that young people's engagements with digital technologies are varied and often unspectacular – in stark contrast to popular portrayals of the digital native. As such, the paper highlights a misplaced technological and biological determinism that underpins current portrayals of children, young people and digital technology.”

Digital literacy may be highly influenced by acceptance of technology. Edward (2010) in a study about Student attitudes towards and use of ICT in course study, work and social activity concludes that “Usefulness and Ease of Use are key aspects of students' attitudes towards technology in all areas of their lives, but ICT is perceived most positively in the work context. The work context also appears as an important driver for technology use in the other two areas of use. There are implications for higher education practitioners in terms of decision making about whether and how to require students to use particular technologies for course study. The evidence suggests that of the various factors that influence use of and perceptions about ICT, its perceived functionality plays a dominant role. Practitioners should not assume that students share their view of what is functional or that a technology does deliver its promised functionality in a particular study context.”

Assessment, positioning and training tools

See also: Assessments of Information Literacy, a compilation by Jon Mueller (North Central College) (as of May 2016, updated on Aug 1. 2014).

Commercial

- iSkills (commercial) is an outcomes-based assessment that measures the ability to think critically in a digital environment through a range of real-world tasks.

- Standardized Assessment of Information Literacy Skills (SAILS). This commercial test is based on ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education (see above).

- Digital literacy/Information Literacy Test (ILT), also based on ACRL standards.

Open

- Digital Literacies Toolkit ( University of Southampton ). Includes specific e-learning literacy tests.

- The JISC Self-assessment tools page lists a number of tools, e.g.

- Digital competences (Cdfop)

- Digital Competency Profiler Based on the General Technology Competency and Use (GTCU) Framework (EILAB, University of Ontario Institute of Technology)

- ProjectDQ Project "Digital Quotient" offers a range of training opportunities and tools for children, parents and others

- Student Sucess is a self-assessment and guidance tool that includes digital literacy.

Bibliography

Cited

- ↑ Hsieh, Y. (2012). Online social networking skills: The social affordances approach to digital inequality. First Monday, 17(4). doi:10.5210/fm.v17i4.3893, http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3893/3192

- ↑ Lankshear, Colin & Michele Knobel,

- ↑ Lankshear, C and Knobel, M. (2013). Front matter and Introduction to A New Literacies Reader: Educational Perspectives. New York: Peter Lang, v-19. pdf

- ↑ Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C. & Leu, D. (2008). Central issues in new literacies and new literacies research. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 25-32). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- ↑ JISC (2014), Developing digital literacies. Provides ideas and resources to inspire the strategic development of digital literacies - those capabilities which support living, learning and working in a digital society. Online, Retrieved May 26 2016 from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-digital-literacies and https://www.jisc.ac.uk/full-guide/developing-digital-literacies (print version)

- ↑ Belshaw, Doug (2011). What is 'digital literacy'? Ed.D thesis, Department of Education at Durham University Word, PDF

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. With eight proficiency levels and examples of use. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/38842

- ↑ Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Carretero Gomez, S., & Van Den Brande, G. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens. Update Phase 1: The Conceptual Reference Model. EU Commission JRC Science for policy report. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2791/11517

- ↑ Desjardins, F. J., Lacasse, R., & Belair, L. M. (2001, June). Toward a definition of four orders of competency for the use of information and communication technology (ICT) in education. Presented at the Computers and Advanced Technology in Education, Banff, Canada.

- ↑ Desjardins, F. J., & VanOostveen, R. (2015). Faculty and student use of digital technology in a “laptop” university. EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology 2015, 990–996.

- ↑ Leu, D. J., Kinzer, C. K., Coiro, J., Castek, J., Henry, L. A. (2013). New literacies: A dual level theory of the changing nature of literacy, instruction, and assessment. In Alvermann, D.E., Unrau, N.J., & Ruddell, R.B. (Eds.). (2013). Theoretical models and processes of reading (6th ed.), pg. 1164. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Available at: http://www.reading.org/Libraries/books/IRA-710-chapter42.pdf

- ↑ Wikipedia, New literacies, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_literacies#Research_in_new_literacies, retrieved april 14 2016

- ↑ James Arthur & Jon Davison (2000) Social literacy and citizenship education in the school curriculum, The Curriculum Journal, 11:1, 9-23 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585170036136

- ↑ PISA 2015 Science Framework (Draft), https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/Draft%20PISA%202015%20Science%20Framework%20.pdf

- ↑ M. J. Scott and G. Ghinea, "On the Domain-Specificity of Mindsets: The Relationship Between Aptitude Beliefs and Programming Practice," in IEEE Transactions on Education, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 169-174, Aug. 2014. doi: 10.1109/TE.2013.2288700

- ↑ K. A. Ericsson , R. Krampe and C. Tesch-Romer, "The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance", Psychol.Rev., vol. 100, pp. 393-394, 1993

- ↑ L. E. Winslow, "Programming pedagogy, A psychological overview", ACM SIGCSE Bull., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 17-22, 1996

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302-314.

- ↑ Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological inquiry, 6(4), 267-285.

- ↑ Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256-273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- ↑ Tzu-Bin Lin, Jen-Yi Li, Feng Deng, & Ling Lee. (2013). Understanding New Media Literacy: An Explorative Theoretical Framework. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 16(4), 160–170. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.16.4.160

- ↑ Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Martin, F. (2014). Development and validation of the educational technologist multimedia competency survey. Educational Technology Research and Development, 62(1), 13-33.

- ↑ Ritzhaupt, Albert, Florence Martin, and Katharine Daniels. "Multimedia competencies for an educational technologist: A survey of professionals and job announcement analysis." Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 19.4 (2010): 421-449.

- ↑ Januszewski, A., & Molenda, M. (2007). Educational technology: A definition with commentary. London: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

- ↑ Ritzhaupt, Albert, Florence Martin, and Katharine Daniels. "Multimedia competencies for an educational technologist: A survey of professionals and job announcement analysis." Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 19.4 (2010): 421-449.

- ↑ Richey, R. C., Fields, D. C., Foxon, M. (with Roberts, R. C., Spannaus, T., & Spector, J. M.) (2001). Instructional design competencies: The standards (3rd ed.). Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information and Technology.

- ↑ JISC (2014). Developing digital literacies, JISC Guide, Retrieved April 13 2016 from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/full-guide/developing-digital-literacies

- ↑ JISC (2015). Developing students' digital literacy, retrieved April 13 2016 from https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/developing-students-digital-literacy

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 American Library Association (ALA). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education, Retrieved, May 10, 2016 from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/informationliteracycompetency PDF of this document

- ↑ ACRL Board, American Library Association (ALA), Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, Retrieved May 10 2016 from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

- ↑ Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. Understanding by Design. (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2004)

- ↑ Jan H. F. Meyer, Ray Land, and Caroline Baillie. “Editors’ Preface.” In Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning, edited by Jan H. F. Meyer, Ray Land, and Caroline Baillie, ix–xlii. (Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers, 2010).

- ↑ Townsend, L., Hofer, A. R., Lin Hanick, S., and Brunetti, K. (2016) Identifying threshold concepts for information literacy: A Delphi study. Communications in Information Literacy, 10 (4).

- ↑ Brunetti, K., Hofer, A. R. and Townsend, L. (2014) Interdisciplinarity and information literacy Instruction: A threshold concepts approach. In C. O’Mahoney, A. Buchanan, M. O’Rourke, & B. Higgs (Eds.), Threshold concepts: From personal practice to communities of practice, Proceedings of the National Academy's Sixth Annual Conference and the Fourth Biennial Threshold Concepts Conference (pp. 89-93), Cork, Ireland: NAIRTL. Download conference proceedings PDF

- ↑ Townsend, L., Brunetti, K., & Hofer, A. R. (2011). Threshold Concepts and Information Literacy. Portal: Libraries And The Academy, 11(3), 853-869. http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/7417

- ↑ Gavriel Salomon. “To Be or Not to Be (Mindful).” Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Meetings, New Orleans, LA, 1994.

- ↑ Thomas P. Mackey and Trudi E. Jacobson. “Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy.” College and Research Libraries 72, no. 1 (2011): 62–78.

- ↑ Eisenberg and Berkowitz (2000). Teaching Information and Technology Skills: The Big6 in Secondary Schools,

- ↑ nformation, Communications, and Technology (ICT) Skills Curriculum Based on the Big6 Skills Approach to Information Problem-Solving By Mike Eisenberg, Doug Johnson and Bob Berkowitz Revised February 2010, http://www.big6.com/media/freestuff/LMC_Big6-ICT_Curriculum_LMC_MayJune2010.pdf

- ↑ Engen, B. K., Giæver, T. H., & Mifsud, L. (2015). Guidelines and regulations for teaching digital competence in schools and teacher education: a weak link?. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10(02), 69-83.

To sort out

- Arthur, C. (2006), What is the 1% rule? The Guardian July 20th. Retrieved November 10th from http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2006/jul/20/guardianweeklytechnologysection2

- BECTA, Web 2.0 technologies for learning at KS3 and KS4 - Project overview, Index page (5 reports)

- Bennett, S., Maton, K., Kervin, L. (2008), "The ‘digital natives’ debate", British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 39 No.5, pp.775-86.

- Burnett, C., Dickinson, P., Myers, J., and Merchant, G. (2006), 'Digital connections: transforming literacy in the primary school.' Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(1) 11-29.

- Carr, Nicholas (2008). "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" The Atlantic

- Coiro, J., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C., & Leu, D. J. (2008). Central issues in new literacies and new literacies research. In J. Coiro, M. Knobel, C. Lankshear, & D. J. Leu (Eds.), Handbook of new literacies research (pp. 1–22). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Cole, M. (2009). Using Wiki technology to support student engagement: Lessons from the trenches. Computers & Education, 52 (1), 141-146.

- Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Initial Test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189-211.

- diSessa, A. (2001), Changing Minds: Computers, Learning, and Literacy. The MIT Press.

- Duderstadt, J. 2004. Higher learning in the digital age: An update on a National Academies study. Paper presented at the 6th annual meeting of EDUCAUSE, Denver, CO, October. PDF, retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET).

- Edmunds, Rob; Thorpe, Mary and Conole, Grainne (2010). Student attitudes towards and use of ICT in course study, work and social activity: a technology acceptance model approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, Early View 27 Dec 2010. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01142.x

- Fisher, M., Baird, D. (2009), "Pedagogical mashup: Gen Y, social media, and digital learning styles", in Hin, L., Subramaniam, R. (Eds),Handbook of Research on New Media Literacy at the K-12 Level, IGI Global, Hershey, PA.

- Gui, M. & Argentin, G. (2011). Digital skills of internet natives: Different forms of digital literacy in a random sample of northern Italian high school students, New Media & Society. Volume 13 Issue 6 http://nms.sagepub.com/content/13/6/963

- Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in people’s online skills. First Monday 7(4).

- Kress, G (2003), Literacy in the new media age. London: Routledge.

- Lanham, R. (1995), 'Digital literacy.' Scientific American, 273, 3 160-160

- Lohnes, S., Kinzer, C. (2007), “Questioning assumptions about students' expectations for technology in college classrooms”, Innovate, Journal of Online Education, Vol. 3 No. 5. PDF, retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET).

- Oblinger, D., and J. Oblinger, eds. 2005. Educating the Net Generation. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE. PDF, retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET).

- Olson, D. (1986), 'Intelligence and literacy: the relationships between intelligence and the techniques of representation and communication.' In Sternberg, (Ed.), Practical intelligence. Cambridge: CUP.

- Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2006). New literacies: Everyday practices & classroom learning (2nd ed.). pg. 65. New York: Open University Press and McGraw Hill.

- Luehrmann, Arthur. "Computer Literacy--What Should It Be?" The Mathematics Teacher vol 74 no 9, Dec 1981.

- Martin, A. (2008). Digital literacy and the ‘digital society’. Digital literacies: Concepts, policies and practices, 30, 151-176.

- Prensky, Marc, 2001 "Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.", On the Horizon 9:1-6. PDF part I reprint,

- Rainie, L., M. Kalehoff, and D. Hess. 2002. College students and the Web: A Pew Internet data memo. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project. Abstract/HTML/PDF, retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET).

- Selwyn, Neil (2009) The digital native – myth and reality, Aslib Proceedings, Volume: 61 Issue: 4. DOI 10.1108/00012530910973776

- Bridges, S.M., Dona, K.L., Deneen, C.C., Diego, J.S., Eichhorn, K., Fluck, A., Gui, X., Gibson, D.C., Huang, R., Ifenthaler, D., Lu, J., Mukama, E., Ren, Y., Spector, J.M., Samspon, D., Warusavitarana, A., & Yang, L.. (2016). Technology Enhanced Formative Assessment for 21st Century Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 19, 58-71.

- Sutherland-Smith, W. (2002), 'Weaving the literacy web: changes in reading from page to screen.' The reading teacher, 55(7), 662-229.

- Snyder, Ilana and Beavis, Catherine 2004, Doing literacy online : teaching, learning and playing in an electronic world Hampton Press, Cresskill, N.J.. Abstract only

- Tadesse, T., Gillies, R. M., & Campbell, C. (2017). Assessing the dimensionality and educational impacts of integrated ICT literacy in the higher education context. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2957

- Tyler, Keith D. (1998). The Problems in Computer Literacy Training: Are We Preparing Students for a Computer Intensive Future?. Writing for the Professions. HTML, retrieved 19:22, 5 December 2011 (CET).

- Wecker, C. (2007). Computer literacy and inquiry learning: when geeks learn less, Journal of computer assisted learning, 23, 133-144, 2007.

- Weller, Martin, The Digital Scholar - How Technology is Transforming Scholarly Practice, Bloomsbury.

- Wolfe, Barbara B. "Achieving Computer Literacy." SIGUCCS Newsletter. Summer 1998. ACM. pp. 29-32.

Links

- DL resources index (JISC Design Studio), Retrieved April 2016.

- Book excerpts, manuscripts and research reports from Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear

- Digital Competence Framework for Educators (DigCompEdu) by the European Commission, 2017.

Humor

- Medieval help desk (English subtitles)

- Medieval help desk (Remake, in English, not as well as the original)