Concepts of computerized embroidery

Introduction

There are many concepts related to computerized embroidery. In this entry we shall try to summarize the most important ones that are of interest to a absolute beginner. Basically, you would start from a vector drawing and the tell the machine to translate it to so-called embroidery objects (another kind of vector drawing) from which stitches then can be generated. Although advanced home user software is pretty smart in converting vector drawings to stitchable sections and the latter to stitch commands, you may have to intervene manually and/or at least set a few parameters in order to get a decent enough result. Read our pieces on Stitch Era (commercial) or InkStitch (open source) if you need to see some more practical examples that deal with beginner's embroidery projects and typical workflows that you could adopt.

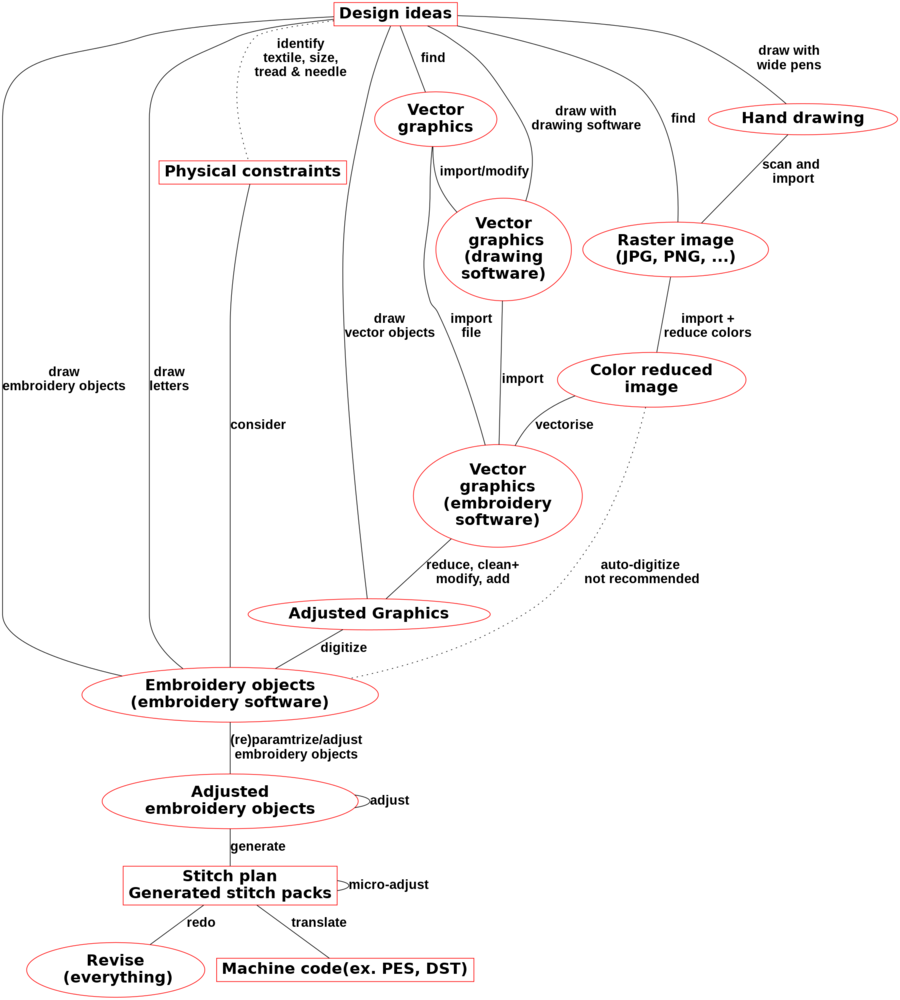

A typical "workflow" for creating an embroidery includes the following steps.

- Create a drawing (by hand or with a drawing software) or download an image

- Import the drawing into an embroidery software

- Convert to editable vector drawing format if the drawing is in raster format

- Adapt the drawing to the constraints of the embroidery (eliminate the fine details, reduce the colors)

- Transform the drawing into "embroidery objects". An embroidery object defines an areas for which embroidery stitches generated according to various parameters specified by the designer and / or the default system

- Adjust / re-adjust these embroidery objects (embroidery types, stitch density, patterns, embroidery order, etc.)

- Convert to executable format for a machine brand (.pes, .art, .jef, .dst etc.)

- Stitch the design (load it into a machine

A slightly more complex - but still not fully complete - workflow model is shown below. As you can see there are several design path that you could take. Good embroidery software should allow to draw and/or import drawings made with standard drawing software such as Illustrator or Inkscape. Then you have to be able to translate the drawing objects into embroidery objects and define their properties such as density, color, type of fill, etc. Through this information, embroidery stitches are generated, which can be edited to make micro-adjustments. All these drawings and other information are saved in a proprietary design file. The last step is to translate the embroidery objects into an executable file (point positions, thread changes, entry/exist instructions) by the embroidery machine. This type of file is not very editable, but easy to convert from one machine format to another.

According to Kathy Jones, the "big three" (problems) of embroidery are puckering, poor fabric coverage or poor registration. “Correct stabilization, correct hooping and correct tension on your embroidery machine” will make your embroidery much more successful. However, there is more to know.

- What thread type to choose

- What backing (solid or solvable fabric on the back side) to use

- How different fabric types behave

- What underlay stitching to use in different situations

- Basic stitch types

- Choosing filling patterns and strategies

- Push/Pull (the fact that a stitch is pulled down when it locks)

- Stitching order (and how to change it)

Threads

Material

Most popular embroidery threads are made from Viscose (also known as rayon) or Polyester. Other materials include cotton, wood and metalized.

Thread thickness

There exist several metrics for thickness and none is really intuitive to understand (like thickness of threads as for climbing ropes). According to Madeira (UK), thread thickness measures are standardized weights (standardized in the sense of statistics). For example:

- In the most popular metric numbering system (Nm or No), higher means finer and lower means thicker. Nm is measured as number of 1000 metre hanks per kilo.

- In the so-called Denier or Tex systems (used for stockings), the opposite is true. Tex is weight in grams of 1000 meters of yarn and Denier is weight in grams of 9000 meters of yarn.

We use either Poly 40 or rayon 40 (the "classic" viscose artificial silk). Both are appropriate for beginners and can be used both on fine fabrics like silk or jersey and rougher/thicker fabrics like jeans or leather.

Some standard weights (Nm/No):

- 75 very fine, e.g. for monograms on silk ties

- 60 fine, e.g. for delicate fabrics and small letters, used with a 60/8 or 65/9 needle

- 50 medium-fine, for medium weight fabrics

- 40 is medium, standard fabric, the most popular weight, used with a 75/11 needle

- 30 medium-thick, for filling larger surfaces, quilts, cross-stitches, used with a 90/14 needle. Topstitch (long eye) is recommended.

- 15 thick, used with a topstitch 100 needle

- 6 very thick (not suitable for a machine)

Thread colors

Thread colors (not surprisingly) are not standardized. Each major thread company has its own with different gamuts, and different sales packs and additions and discontinuations etc. The biggest manufacturer is Madeira, others include Janome, Robison-Anton, Isacord, Mettler, and Gunold/Sulky. None of these will overlap their naming conventions. The only significant stabilizing force is Pantone™ which is a private company, well known and regarded throughout the garment and color industries. However, here, unlike with most of computerized embroidery questions about Color Distance (how similar will an average human eye see these particular colors) and the algorithms utilized in determining those are well established, and largely standardized with a rich firm scientific history. The best results being LAB-Delta E00, as well as progressively less powerful algorithms with notable speed advantages. The emphasis with thread colors is that they be consistent with themselves rather than consistent with threads offered by other companies or with the named gamuts released by Pantone (though many companies will release Pantone conversion charts which give the thread color to nearest Pantone color within some amount of error).

There are also a number of other considerable elements within the realm of thread, such as specialty threads like glow-in-the-dark, various metallics, color changing when exposed to sunlight, and considerations like the Matte finish on the thread. With companies like Madeira offering a popular "frosted matt" thread set which offer heavily reduced shine. Or companies noting which threads they have which are fire resistant.

There's also thread weight to consider which is namely how much does 1000 meters of the thread weigh or else how far 1kg of thread stretches, which taken as meaning how thin or thick is the thread. Standardly most thread used is 40wt, others are 60wt (thin), 100wt (very thin), 30wt (thick) and 12wt (very thick)

Also, from experience most thread company data to establish some RGB values for the color of the thread is bad. Well understood properties like different lighting and different white balances can often greatly bias a color. To get the RGB value to a very precise degree (which I've had to do) the best method is buy thread charts from the company (with actual fabric swatches of the thread) and put them into a flatbed scanner which has a known and well established white balance and take the average color over many pixels within the scanned swatch. Which will work for anything without strong fluorescent properties. Usually for a lot of projects good enough colors are sufficient and in those cases the color charts from various sources may be perfectly acceptable. However, even the numbers the companies use internally are known to be quite flawed.

Read more about thread color in Embroidery thread color and chart.

Needles

Needles should be adapted to the thread type and weight. Needles for embroidery are usually a bit different from other types of sewing needles: the tip is less sharp and the eye (opening for the thread) slightly bigger, but people also seem to use other sewing needles for embroidery.

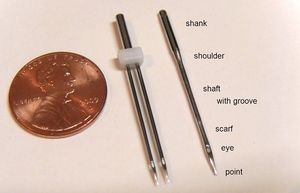

According to Wikipedia based on Lydia Morgan's "Machine-needle know-how", needles have the following structure (from top to tip)

- shank - clamped by the sewing machine's needle holder

- shoulder - where the thick shank tapers down to the shaft

- shaft - a length suitable for driving the eye and thread through the material and down to the bobbin. The shaft is the longest part and determines the size (diameter)

- groove - cut in the back of the shaft to release the thread into a loop that aids the hook or shuttle to pick up the thread

- scarf - provides extra room for the hook or shuttle to pass close by

- eye - the hole, carries the thread

- point - penetrates the material by parting the threads or cutting a hole

In principle there exist only two kinds of system with respect to how it is attached to the machine, length etc.:

- System 130/705 H (shank has a flat side) ... far more popular since much more stable

- System 287 WH (round cylinder for the shank)

Needle size is in 1/100 mm sometimes assorted with a Singer size number.

Typical sizes (shaft diameter) are:

- 100/16 = 1.0 mm

- 90/14 = 0.9 mm

- 80/12 = 0.8 mm

- 75/11 = 0.75 mm

- 70 = 0.7 mm

- 65/9 = 0.65mm

- 60 = 0.6 mm

Size 75/11 (0.75 mm) with #40 thread is most popular. Use finer needles, e.g. 65/9 (0.65mm) or 60 (0.6 mm) for #60 thread, and 90/14 (0.9 mm) ones for #30 thread. Thicker threads require more tension, and thinner threads less.

Read more in the embroidery and sewing needle article.

Hooping

Correct hooping together with appropriate backing and pull compensation are important factors for creating embroidery that will stay flat (more or less) look like on the computer screen. There are two major "test" that tell if hooping is well done:

The snow plow test

Glide your finger on the hooped tissue. It should not create "waves"....

The drum test

Tap on the hooped textile. If it sounds like a drum you are fine. This applies to non-elastic tissues and elastic tissues that you stabilized (as you should).

Read more in Hooping and stabilizing in computerized embroidery.

Backing

Backing also called stabilizer is either a woven cutaway or tearaway fabric or some type of solvable foil that are used underneath the fabric to provide some stability and support.

Underlay

Underlay is a set of sparse stitches outlining the final design, that will be covered by dense stitches and thus invisible in the final embroidered work.

Underlay will stabilize a stretchable fabric for a section that you would like to stitch. Underlays also can be used to create a 3D effect or otherwise change the look of stitched layer on top. Finally, underlay is also used to even out a surface, e.g. tack down sticking out threads on towels or flatten out corduroy.

Here is a detailed introduction.

There are several kinds of patterns used, however one could distinguish the following three families of underlay:

- No underlay

- Soft (little)

- Hard (a lot)

In addition both soft and hard underlays then can use different patterns like:

- Some kind of lines that are orthogonal to the final stitches. E.g. for an "o" letter you would use a circle, for a larger filled pattern a rectangle.

- ZigZag

- Some kind of diagonal lattices, .e.g \\\ or XXX

Additional reading: Underlay, what lies beneath by Erich Campbell

Fabric and fiber types

Fabric has an impact on the result. In particular, certain types of fabric are more difficult since they are stretchable. Stretchable fabric could be stabilized in several ways that can be combined:

- By using some backing

- By using an appropriate underlay

- By using some pull compensation (?)

Other fabric such as bath towels and fleece present the problem that fine-grained stitching can "get visually lost".

Most common fabric types are: Canevas, Cotton, Curdory, Denim, Fleece, Jackets, Leather, Nylon, Lycra, Knit wool, Terry (towels), Twill, Wovens.

Stitch types

According to Wikipedia, retrieved 12:00, 2 June 2011 (CEST), an embroidery stitch, “is defined as the movement of the embroidery needle from the backside of the fabric to the front side and back to the back side. The thread stroke on the front side produced by this is also called stitch. In the context of embroidery, an embroidery stitch means one or more stitches that are always executed in the same way, forming a figure of recognisable look. Embroidery stitches are also called stitches for short. Embroidery stitches are the smallest units in embroidery. Embroidery patterns are formed by doing many embroidery stitches, either all the same or different ones, either following a counting chart on paper, following a design painted on the fabric or even working freehand.”

Read embroidery stitch type for more information.

Push / Pull

Push and Pull refer to the idea that a fabric can be either pulled in or pushed out by the stitches. This typically happens when you fill larger surfaces. For example, a circle can become an oval. The first two following pictures show anti- and pro-nuclear logos between 5 and 7cm in diameter. The third picture shows distortion in the center-outside axis. The large yellow sold circle was replaced by light fill pattern using running stitches.

|

|

|

Both yellow circles were printed with a quite solid underlay that ran diagonally. Same for the red area and that was totally useless. The underlay probably had the effect to insure that the embroidery was flat, but it could not prevent the pull effect. We did not try using a backing.

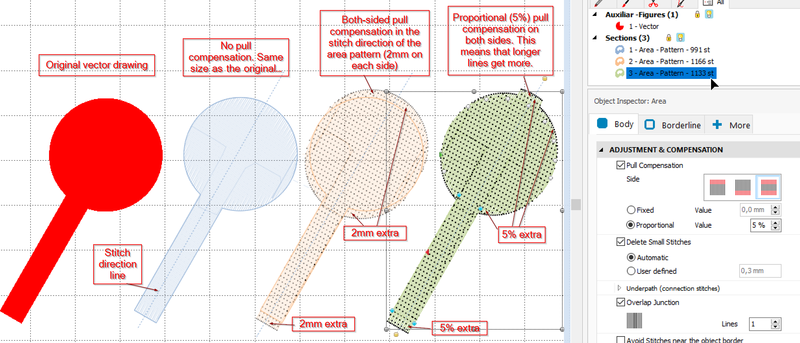

- Pull compensation

- Pull compensation is done by the software: it slightly widens the widths of stitch. It is usually applied to two sides of a section since the pull happens in one direction. The pull direction should depend on the kind of filling used and the underlying fabric, but on the software side pull compensation is done along the lines of the area pattern

- Typically, one could add between 2 and 10% if we understood right. The larger solid circles above probably need 10%, but so far, we didn't do any tests with these.

- Lower density

- Some software, e.g. Stitch Era, uses 5 lines /mm density, which is quite a lot. If your design allow it, lowering it to 4 lines/mm may help a bit.

- Different patterns

- Instead of generating a homogeneous left-right or up-down pattern, you might use one that pulls in both directions or alternatively use some kind of checker pattern.

- Don't stitch large areas

- Another solution is not to print such large areas, i.e. leave out holes where other parts are to be stitched. An example is shown in the next picture. This logo was digitized from a bitmap (including the lettering) and doesn't have any over-stitching.

Stitching order

... is crucial of course, since stitches may overlap a bit. I believe that one could adopt the following heuristics:

- lines (in particular a contour) should be printed last

- larger areas before tiny areas inside (on top)

- neighboring areas using the same thread should be stitched in line, in order to avoid jump stitches.

- same thread color in one shot

... of course some of these rules are contradictory. It's probably best to print a test object and see if it makes sense to change order. In addition one also can overstitch things like lines. A high-end embroidery machine allows to selectively print layers (threads).

Thread tension

Thread tension can be adjusted in any machine, tension is usually achieved by a kind of wheel pressing the thread.

Good tension can be seen as follows:

- There should be no bobbin thread (usually white or black) shown on top

- There should be very little thread shown underneath.

To do:

- First of all, make sure that you hoop correctly (in particular woven fabrics must be tightly stretched)

- If you see loops (or even a nest) underneath, then tighten the tension on top. But before doing so verify that you thread according to instructions.

- If you see white (bobbin color) on top, then loosen on top.

You also can try to de/increase the bobbin tension. Before doing so make sure that there is no dust under the tension adjusting spring (p. 286)

In addition:

- If stitches are not tight, then tighten, however this may augment the "pull". Therefore increase slowly.

- If the thread breaks (and not because the thread is somehow stuck), then you could make tension a bit less tight.

- You also should check the needle. In particular it should not be sticky and the thread should come through it easily

Special tips for the Brother PR1050X

- The tension disc should rotate easily (but not too easily) when you pull the thread. After some month (or years?) of usage you may have to remove the tension dials and remove the accumulated dust.

- The thread should roll out of the bobbin case smoothly. If, after cleaning between the spring, it still takes too much force then untighten the spring, else tighten.

Links

- Embroidery Glossaries

- Glossary of terms at embroideryauthority.com

- Digitizing Dictionary by Kathy Jones

- Kathy Jones Tutorials has a series of interesting tutorials, e.g

- Density for Machine Embroidery

- The Perfectly Digitized Design

- The Perfectly Embroidered Design

- A Stitcher’s Guide to Pull Compensation by Kathy Jones.

- Needles

- Needles – What the Home Sewer Needs to Know 2004, Web of Thread, Inc.

- Sewing machine needle (Wikipedia)

- Nadel (Wikipedia, German)

- Schmetz Needle Guide (PDF)

- Machine-Needle Know-How by Lydia Morgan, Threads Magazine #94 (2008), pp. 59-61

- Stitches

- Sharon b's Dictionary of Stitches for Hand Embroidery and Needlework (also useful for people interested in machine embroidery).

- Embroidery stitch (Wikipedia)

- Virginia Colton (1979). (ed). Reader's Digest Complete guide to needlework, Reader's Digest Association. ISBN 0895770598. For hand embroidery and other needle craft. Probably a good 2nd hand buy.

- Book lists

- lacis, an online story has books on Machine Embroidery

Bibliography

- Galina Ripka, Аnatoly Mychko, Inessa Deyneka (2014). The analysis of machine embroidery stitches types classification, TEKA. Commission of motorization and energetics in agriculture (Teka Komisji Motoryzacji i Energetyki Rolnictwa), Vol. 14, No.2, 120-126, http://agro.icm.edu.pl/agro/element/bwmeta1.element.agro-8789fa3f-f7f8-4072-8d67-ad669cc45e72/c/15_120-126.pdf