« Analyse de données qualitatives » : différence entre les versions

mAucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| Ligne 33 : | Ligne 33 : | ||

* De solides qualités « d’investigateur », comprenant de l’obstination, la capacité à faire parler les gens, et la capacité à prévenir une clôture prématurée". | * De solides qualités « d’investigateur », comprenant de l’obstination, la capacité à faire parler les gens, et la capacité à prévenir une clôture prématurée". | ||

Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (2003, p. 78). Analyse des données qualitatives. 2e édition. De Boeck Université.}} | Miles, M. & Huberman, M. (2003, p. 78). Analyse des données qualitatives. 2e édition. De Boeck Université.}} | ||

== Les différentes méthodes d'analyse de données qualitatives == | |||

=== Les méthodes non spécialisées === | |||

L'extrait suivant est tiré de Savin-Badin, M. & Howell Major, C. (2013, pp. 434-440). Qualitative research. The essential guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge. "Data analysis is a systematic search for meaning. It is a way to process qualitative data so that what has been learned can be communicated to others. Analysis means organising and interrogating data in ways that allow researchers to see patterns, identify themes, discover relationships, develop explanations, make interpretations, mount critiques, or generate theories. It often involves synthesis, evaluation, interpretation, categorisation, hypothesising, comparison, and pattern finding. It always involves what Wolcott calls « mindwork »…. Researchers always engage their own intellectual capacities to make sense of qualitative data”. (Hatch, 2002, p. 148) (…) | |||

There are a number of analytical approaches from which qualitative researchers may choose. Which method to choose is a critical decision, because the method invariably influences the focus of data analysis and thus the results. (…) | |||

A '''keyword analysis''' is exactly what it sounds like. It involves searching out words that have some sort of meaning in the larger context of the data. The idea is that, in order to understand what the participants say, it is important to look at the words with which they communicate. (…) | |||

'''Constant comparison''' is an analytical method that researchers use to develop themes and ultimately generate theory. (…) The constant comparison process involves the following basic steps : | |||

* Identifiy categories in events and behavior. | |||

* Name indicators in passage and code them (open coding) | |||

* Continually compare codes and passages to those already coded to find consistencies and differences | |||

* Examine consistencies or patterns between codes to reveal categories | |||

* Continue the process until the category « saturates » and no new codes related to it are identified. | |||

* Determine which categories are the central focus (axial categories) and, thus, form the core category. (…) | |||

'''Content analysis''' is the process of examining a text at its most fundamental level : the content. It is an analysis of the frequency and patterns of use of terms or phrases and has been applied to a range of research approaches. (…) | |||

'''Domain analysis''' is a collection of categories that are related. For example the domain of chocolate would include sweet, bitter and semisweet. (…) | |||

'''Thematic analysis''' is a method of identyfing, analyzing and reporting patterns in the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). There is no clear agreement for what thematic analysis is or how one does it, although it appears that much of what qualitative researchers do when analyzing data under the generalist term of qualitative data analysis is actually thematic analysis (Braun and Wilkinson 2003). (…) The method provides a general sense of the information through repeated handling of the data. The idea is to get a feel for the whole text by living with it prior to any cutting or coding. It is not the most scientific sounding method but we believe it to be one of the best. The researcher can rely on intuition and sensing, rather than being bound by hard and fast rules of analysis. Braun and Clarke (2006) recommend doing the following when conducting thematic analysis: | |||

* familiarize yourself with your data | |||

* generate initial codes | |||

* search for themes | |||

* review themes | |||

* define and name themes | |||

* produce the report. | |||

What is unique about thematic analysis is that it acknowledges that analysis happens at an intuitive level. It is through the process of immersion in data and considering connections and interconnections between codes, concepts and themes that an « aha » moment happens." | |||

== Principes de l'analyse de données qualitatives == | == Principes de l'analyse de données qualitatives == | ||

Version du 15 janvier 2019 à 14:31

| Manuel de recherche en technologie éducative | |

|---|---|

| Page d'entrée du module Analyse de données qualitatives |

|

| ▬▶ | |

| ⚐ brouillon | ☸ intermédiaire |

| ⚒ 2019/01/15 | ⚒⚒ 2015/08/27 |

| Autres pages du module | |

Introduction

Ce module présente différents aspects de l’analyse des données qualitatives. Nous allons présenter une approche structurelle «moderne» qui requiert du chercheur de coder les données. Ces codes lui permettront alors de mener divers types d’analyses, dont nous allons vous montrer quelques exemples.

Objectifs d’apprentissage

- Apprendre à coder des données et créer des manuels de codage (codebooks)

- Apprendre les fondements de quelques techniques d’analyse descriptive (notamment les situations et les rôles)

- Apprendre les fondements de quelques techniques d’analyse causale

Caractéristiques d'un chercheur qualitatif

"un bon chercheur qualitatif est doté des caractéristiques suivantes:

- Une certaine familiarité avec le phénomène et le milieu étudiés,

- Un intérêt affirmé pour la dimension conceptuelle,

- Une approche pluridisciplinaire par opposition à une formation restreinte ou cantonnée à une seule discipline,

- De solides qualités « d’investigateur », comprenant de l’obstination, la capacité à faire parler les gens, et la capacité à prévenir une clôture prématurée".

Les différentes méthodes d'analyse de données qualitatives

Les méthodes non spécialisées

L'extrait suivant est tiré de Savin-Badin, M. & Howell Major, C. (2013, pp. 434-440). Qualitative research. The essential guide to theory and practice. London: Routledge. "Data analysis is a systematic search for meaning. It is a way to process qualitative data so that what has been learned can be communicated to others. Analysis means organising and interrogating data in ways that allow researchers to see patterns, identify themes, discover relationships, develop explanations, make interpretations, mount critiques, or generate theories. It often involves synthesis, evaluation, interpretation, categorisation, hypothesising, comparison, and pattern finding. It always involves what Wolcott calls « mindwork »…. Researchers always engage their own intellectual capacities to make sense of qualitative data”. (Hatch, 2002, p. 148) (…)

There are a number of analytical approaches from which qualitative researchers may choose. Which method to choose is a critical decision, because the method invariably influences the focus of data analysis and thus the results. (…)

A keyword analysis is exactly what it sounds like. It involves searching out words that have some sort of meaning in the larger context of the data. The idea is that, in order to understand what the participants say, it is important to look at the words with which they communicate. (…)

Constant comparison is an analytical method that researchers use to develop themes and ultimately generate theory. (…) The constant comparison process involves the following basic steps :

- Identifiy categories in events and behavior.

- Name indicators in passage and code them (open coding)

- Continually compare codes and passages to those already coded to find consistencies and differences

- Examine consistencies or patterns between codes to reveal categories

- Continue the process until the category « saturates » and no new codes related to it are identified.

- Determine which categories are the central focus (axial categories) and, thus, form the core category. (…)

Content analysis is the process of examining a text at its most fundamental level : the content. It is an analysis of the frequency and patterns of use of terms or phrases and has been applied to a range of research approaches. (…)

Domain analysis is a collection of categories that are related. For example the domain of chocolate would include sweet, bitter and semisweet. (…)

Thematic analysis is a method of identyfing, analyzing and reporting patterns in the data (Braun and Clarke 2006). There is no clear agreement for what thematic analysis is or how one does it, although it appears that much of what qualitative researchers do when analyzing data under the generalist term of qualitative data analysis is actually thematic analysis (Braun and Wilkinson 2003). (…) The method provides a general sense of the information through repeated handling of the data. The idea is to get a feel for the whole text by living with it prior to any cutting or coding. It is not the most scientific sounding method but we believe it to be one of the best. The researcher can rely on intuition and sensing, rather than being bound by hard and fast rules of analysis. Braun and Clarke (2006) recommend doing the following when conducting thematic analysis:

- familiarize yourself with your data

- generate initial codes

- search for themes

- review themes

- define and name themes

- produce the report.

What is unique about thematic analysis is that it acknowledges that analysis happens at an intuitive level. It is through the process of immersion in data and considering connections and interconnections between codes, concepts and themes that an « aha » moment happens."

Principes de l'analyse de données qualitatives

Avec l’analyse qualitative, le chercheur essaye d'identifier une structure dans les données (comme le font les techniques exploratoires quantitatives). Pour ce faire, deux types de techniques d’analyse sont couramment utilisés:

- Une matrice est une tableau qui engage au moins une variable, e.g.

- Les tableaux de variables centrales selon les cas (équivalents aux statistiques descriptives simples telles que les histogrammes)

- Les tableaux croisés permettant d’analyser comment deux variables interagissent

- Un graphique (réseau ou carte conceptuelle) permet de visualiser les liens entre les données:

- liens temporels entre des événements

- liens de causalité entre plusieurs variables

- diagrammes d'activités et de processus

- etc.

Analyse = mise en tableaux et visualisations diverses des données

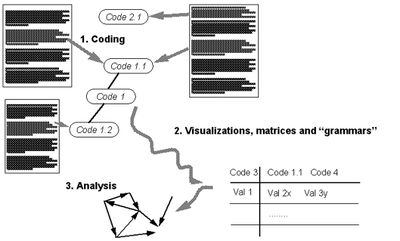

L’analyse des données qualitatives comprend généralement une série d’étapes itératives liées. Le principe général de la plupart des méthodes d’analyse des données qualitatives est le suivant:

- Les données doivent être codées et indexées pour pouvoir être retrouvées pour l’analyse. Plus précisément, le codage d’informations permet d’identifier les variables et les valeurs. Une telle analyse systématique des données augmente la fiabilité et la validité de construction, i.e. vous devez observer tout ce qui permet de mesurer les concepts.

- Vous devez ensuite créer des visualisations, des matrices, des grammaires, etc. pour interpréter les données.

- Vous devez ensuite interpréter, faire émerger du sens, de ces visualisations.

- Vous devez finalement vérifier la pertinences de vos analyses et interprétations.

Quelques conseils:

- Lorsque vous utilisez ces techniques, gardez toujours un lien avec la source (autrement dit, les données codées).

- Efforcez-vous de faire rentrer chaque matrice ou graphique dans une seule page (ou assurez-vous de pouvoir imprimer les travaux réalisés à l’aide d’un ordinateur sur une page A3) afin d'avoir une vue d'ensemble de toutes les données.

- Privilégiez une vision synthétique, mais préservez suffisamment de détails pour rendre vos artefacts interprétables.

- Consultez des manuels spécialisés e.g. Miles, Huberman & Saldaña (2014) pour des procédures validées et/ou inspirez-vous de travaux de recherche qualitative publiés dans votre domaine.

Avant de commencer

Avant que nous expliquions le codage et l’analyse, nous devons vous conseiller de recourir à un système qui vous permettra de conserver vos documents et vos idées de manière sûre.

- Rédigez des mémos pour conserver vos idées. Il est utile d’écrire des petits mémos lorsqu’une idée intéressante surgit à la suite d’une observation.

- Créez des fiches de contacts qui vous permettront de garder en tête votre travail de terrain. Après chaque contact (téléphone, interview, observation, etc.), rédigez un document bref qui devrait inclure:

- Une étiquette claire pour des raisons d’indexation (nom de fichier ou étiquette en papier), e.g. CONTACT_senteni_2005_3_25.doc.

- Type de contact, date, lieu, et lien vers les notes de l’entretien, transcriptions.

- Thèmes principaux abordés et variables de recherche traitées (ou renvoi vers la page de l’entretien).

- Premières remarques interprétatives, spéculations nouvelles, éléments à traiter dans un deuxième temps.

- Indexez vos notes d’entretiens:

- Conservez vos transcriptions (ou fichiers audio/vidéo ou cassettes audio) en lieu sûr.

- Assignez un code à chaque «texte», e.g. INT-1 ou INTERVIEW_senteni_3_28-1. Le même code pourrait être utilisé comme nom de fichier.

- Vous pourriez également "agrafer" une fiche de contact avec les notes (voir ci-dessus)

- Numérotez les pages si vous prenez des notes à la main (elles pourraient tomber par terre…)

- Ne vous fiez pas trop à vos disques durs, faites des sauvegardes fréquentes!

Différence entre résultats et recherche en cours

Avant de commencer votre analyse, réfléchissez bien à ce dont vous avez besoin (échantillon) pour pouvoir répondre à vos questions de recherche et pensez à consulter des ouvrages de référence pour choisir la méthode la plus appropriée. Remarque: dans le cas de nombreuses études qualitatives rapportées sous forme d'articles dans la littérature, vous remarquerez que les chercheurs présentent souvent uniquement des citations d’entretiens. Ces citations sont choisies pour représenter des opinions spécifiques et sont arrangées selon un ordre logique, e.g. des sujets émergeant dans la perception de l’utilisateur sur des problématiques données. Cependant, avant de rédiger leur article, ces chercheurs ont utilisé des techniques d’analyse comme celles mentionnées dans l'ouvrage de Savin-Baden & Howell Major (2013, pp. 434-447).