Cultural competence

Introduction

This piece attempts to summarize some elements of cultural competence and related concepts, such as cultural intelligence, global competence or global citizenship. Cultural competence also is known as intercultural or cross-cultural competence.

This page also includes a series of sub-pages that include various instruments (surveys, self-assessment questionnaires, rubrics):

- Acculturation index (Ward and Rana-Deuba)

- Behavioral Assessment Scale for Intercultural Communication Effectiveness

- Business Cultural Intelligence Quotient

- Cause of culture shock scale

- Cross-Cultural Adaptability Inventory

- Cross-Cultural Orientation Inventory

- Cultural Competence Assessment Instrument

- Cultural Intelligence Scale

- Defense Language Office Framework for Cross-cultural Competence

- Global Competence Aptitude Assessment

- Integrated Measure of Intercultural Sensitivity

- Intercultural Adjustment Potential Scale

- Intercultural Development Inventory

- Intercultural Effectiveness Scale

- Intercultural Knowledge And Competence Value Rubric

- Intercultural Sensitivity Inventory

- Intercultural Sensitivity Scale

- Measurement of Horizontal and Vertical Individualism and Collectivism

- Multicultural Personality Questionnaire

- Satisfaction with life scale

- Self-efficacy scale for adolescents

- Sociocultural Adaptation Scale

- Test to Measure Intercultural Competence

- Vancouver cultural acculturation index

- Global Perspective Inventory items 2012

- cultural intelligence self-assessment

- global competence survey items (Bill Hunter)

Definitions

Cultural competence, i.e. being able to cope with cultural diversity is becoming increasingly important. Cultural competence can been seen as a subset of so-called global competence laying the foundations for "global citizenship". With increasing cultural diversity as a result of globalization, intercultural competence (IC) to interact and to co-exist in multicultural environments is recognized as being very important. (Corder and U-Mackey, 2015).

Cultural competence is a form of literacy, but note that the term "cultural literacy" often seems to refer to simple facts knowledge (history, geography, etc.). The latter can be seen as one of the prerequisites for cultural competence. Interestingly Hirsch et al.'s dictionary of cultural literacy [1] was seen as basis for good information processing [2]

Cultural competence seems to defined as either a list of attributes (traits, knowledge, attitudes, skills, behavior sets, etc.) of an individual or more simply as the ability to interact effectively with members of foreign cultures. The latter (being able to interact) is related to the former.

Byram (1997) [3] cited by Deardorff (2004) [4] defines interculturual competence as:“Knowledge of others; knowledge of self; skills to interpret and relate; skills to discover and/or to interact; valuing others’ values, beliefs, and behaviors; and relativizing one’s self. Linguistic competence plays a key role”. In Deardorffs (2004:184), Delphi study, the following definition achieved the highest rating: [Intercultural competence is] “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes.”. "Auxiliary" skills identified included “skills to analyze, interpret, and relate as well as skills to listen and observe. Cognitive skills emerged including comparative thinking skills and cognitive flexibility. These skills point to the importance of process in acquiring intercultural competence and the attention that needs to be paid to developing these critical skills”.

Cross et al. (1998), in the context of workplace diversity, laid the foundation of many further studies that have more practical aims: “Cultural competence is a a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enables that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations”. For exemple, Heyward (2002) cited by Deithl & Prints (2008), defines intercultural literacy as the competencies, understandings, attitudes, language, proficiencies, participation and identities necessary for effective cross-cultural engagement.

Culture itself is difficult to define. Billmann-Mahecha (2003) [5] defines it [translated] in the following way: “Culture can be characterized as a character, knowledge, rule and symbol system that structures on on hand the human action space, and on the other hand is constructed and altered through the implementation of actions and their practice.” In more simple words, it is something that guides our activities, but that is also reshaped by those.

Hunter (2004) [6] argues that “that the most critical step in becoming globally competent is for a person to develop a keen understanding of his/her own cultural norms and expectations: a person should attempt to understand his/her own cultural box before stepping into someone else’s.”

Reasearch and common sense agree that cultural differences do exist. On also can argue that cultures have common traits, and that people are far more similar across cultures than they are different (Spitzberg 2013) [7]. Since people (and not cultures in the abstract) communicate, Spitzberg (p. 432) also argues that “a theory of intercultural communication competence is necessarily a subset of a theory of interpersonal communication competence”. And furthermore: “To the extent that culture plays a role, it plays it through the motivation, knowledge, and skills of the interactants involved”.

The field seems to be divided according to areas of interest and also affiliation to an established field of study. With respect to application, we so far identified the following major areas of research and development:

- Health care

- Higher education (Internationalization of campuses, study abroad, and integration of minorities)

- International business

The first two seem to very popular in the USA and for diverse reasons, one of which is related to minority issues.

In summary we can say that cultural competence is multi-dimensional construct that is not always perceived and used in the same way. Probably most authors and experts could agree that cultural competence includes at least three dimensions:

- affective (intercultural sensitivity)

- cognitive (intercultural awareness)

- behavioral (intercultural effectiveness)

Models of cultural competence

Most cultural competence models are either component models, or process models or both. Component models can be hierarchical.

Intercultural commmunication

Intercultural communication competence can be seen as a specialisation of interpersonal communication competence.

According to Deardorff (2004:35), Chen and Starosta (1999) [8] define “intercultural communication competence” as “the ability to effectively and appropriately execute communication behaviors that negotiate each other’s cultural identity or identities in a culturally diverse environment” (p. 28). They outline three key components of intercultural communication competence: intercultural sensitivity (affective process), intercultural awareness (cognitive process), and intercultural adroitness (behavioral process), defined as verbal and nonverbal skills needed to act effectively in intercultural interactions.”.

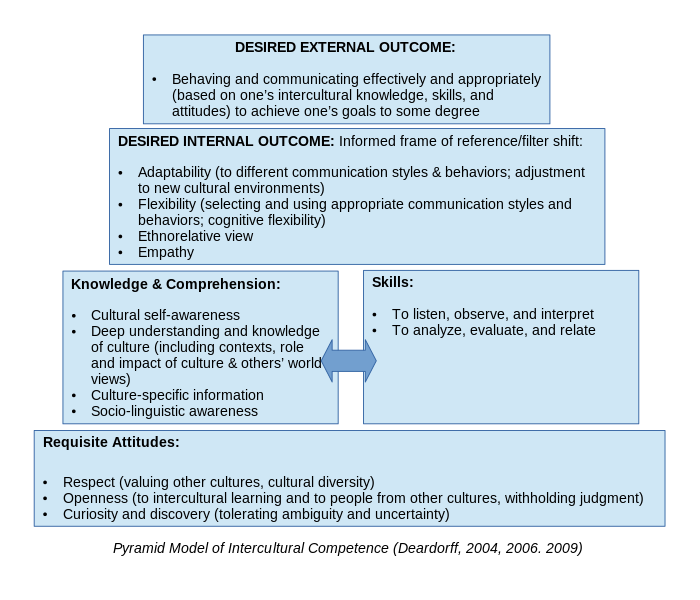

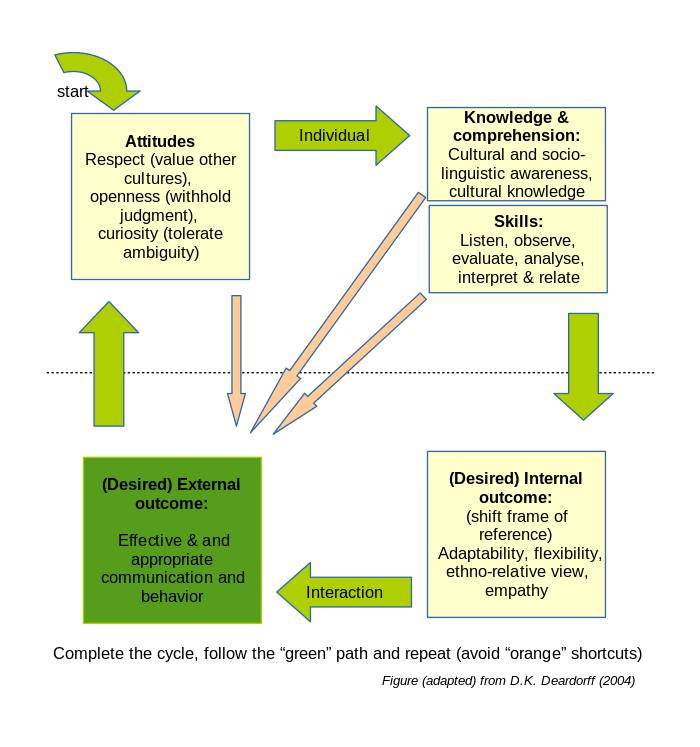

Deardorff (2004:196) in her PHD thesis and subsequent publications developed a pyramid model that formulates two underlying hypothesis: The degree of intercultural competence depends on the acquired degree of underlying elements, in particular, from personal level (attitudes) to interpersonal/interactive level (outcomes). Darla K. Deardorff's model [9] includes 5 components. Below is summary of a component model presented in Theory Reflections: Intercultural Competence Framework/Model (retrieved Feb 2016).

1. Attitudes: respect, openness, curiosity and discovery. Openness and curiosity imply a willingness to risk and to move beyond one’s comfort zone. Respect demonstrate to others that they are valued.

2. Knowledge: cultural self-awareness, culture-specific knowledge, deep cultural knowledge (including understanding other world views, and sociolinguistic awareness. The most important element is understanding the world from others’ perspectives.

3. Skills (addressing the acquisition and processing of knowledge): observation, listening, evaluating, analyzing, interpreting, and relating.

4. Internal Outcomes: flexibility, adaptability, an ethnorelative perspective and empathy. If attained, individuals are able to see from others’ perspectives and to respond to them according to the way in which the other person desires to be treated.

5. External Outcomes is “the effective and appropriate behavior and communication in intercultural situations.

Between these dimensions there is a dependency. Desired external outcomes rely on desired internal outcomes and the latter rely on skills and knowledge. Skills and knowledge requires requisite attitudes. The full pyramid is shown in the figure below.

desired external outcome (communicating effectively)

desired internal outcome (adaptability, flexibility, ethnorelative view, empathy

Knowledge and comprehension <--> Skills

requisite attitudes (respect, openness, curiosity)

This pyramid model then can be turned into a process model. While it is possible to work on desired outcomes directly from attitudes or knowledge/comprehension or skills, it is preferable to start with attitudes, then work on knowledge and comprehension as well as skills, then work on the internal frame of reference.

Since attitude, knowledge, and skill acquisition and creating new frames of reference are tied to experience we also could interpret this model as perpetual cycle that just emphasizes that without having appropriate attitudes, certain knowledge and skill cannot be properly acquired. Useful and operational frames of reference in turn must be grounded in solid knowledge and know-how. Finally effective behavior and communication must be aligned with deeper beliefs.

Derald Wing Sue (2001:abstract) [10] proposed “multidimensional model of cultural competence (MDCC) incorporates three primary dimensions: (a) racial and culture-specific attributes of competence, (b) components of cultural competence, and (c) foci of cultural competence.”

The MDCC allows for the systematic identification of cultural competence [of various US residents or citizens] in a number of different areas. It is a factorial combination of 3 x 4 x 5 items (below).

- 1. Components: Awareness, Knowledge, and Skills)

- 2. Foci: Individual, Professional, Organizational, and Societal

- 3. Racial and culture specific: African American, Asian American, Latino/Hispanic American, Native American, and European American

Aculturation

Aculturation strategies refer to the various ways in which groups and individuals seek to aculture. (Bennet, 2015:3). There are two issures concerning both the dominant and the nondominant group:

- Maintaining one’s heritage culture and identity (+/-)

- Seeking relationships to other cultural groups (+/-)

Combining the two dimensions we can define four strategies of ethnocultural groups and for larger societies.

| Issue 1: Maintenance of heritage culture and identity | |||

| + | - | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Issue 2: Relationships sought among groups | + | Integration | Assimilation |

| - | Separation | Marginalization | |

| Issue 1: Maintenance of heritage culture and identity | |||

| + | - | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Issue 2: Relationships sought among groups | + | Integration | Assimilation |

| - | Separation | Marginalization | |

Jean Phinney () Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; refs with no name must have content developed a very similar typology based on the degree of identification with both one's own ethnic group and the majority group

h“this model suggests that there are not only the two acculturative extremes of assimilation or pluralism but at least four possible ways of dealing with ethnic group membership in a diverse society (Berry et al., 1986). Strong identification with both groups is indicative of integration or biculturalism; identification with neither group suggests marginality. An exclusive identification with the majority culture indicates assimilation, whereas identification with only the ethnic group indicates separation.” (p. 502)

| Identification with ethnic group | ||

|---|---|---|

| Identification with majority group |

Strong | weak |

| Strong | Aculturated Integrated Bicultural |

Assimilated |

| Weak | Ethnically identified Ethnically embedded Separated Dissociated |

Marginal |

Acculturation has been measured with survey instruments, in particular by John Berry and associates. Ward and Rana-Deuba distinguish between 21 dimensions and a related questionnaire includes both attitudes and behavioral items [11]

The simpler Cultural competence/Vancouver cultural acculturation index includes only 21 items [12]

Van Selm et al. (1997) conducted a study of life satisfaction and competence of Bosnian refugees in Norway [13]. The questionnaire include the following components: Locus of control scale, acculturation attitude scale, majority attitude scale, social support scale, life satisfaction scale and competence scale.

Cultural sensitivity

Chen and Starosta (1997) [14] in their "review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity" identified the following components:

- Self-esteem. It is based on “one's perception of how ell on can develop his or potential in a social environment (Borden, 1991).” (p.7). Persons with hight self-esteems seem have an optimistic outlook that instils confident in interaction with others.

- self-monitoring: “a person's ability to regulated behaviour in response to situational constraints” (p.8)

- open-mindedness: “willingness of individuals to openly and appropriately explain themselves and to accept other's explanations” (p.8)

- Empathy: project oneself into another person, step into another person's shoes.

- Interaction involvement: ability to perceive the topic and situation, comprised of responsiveness, perceptiveness, and attentiveness

- Suspending judgement: being able to sincerely listen to others during intercultural communication.

Chen and Starosta cultural sensitivity from interculturual awareness and interculturual competence. Cultural sensitivity, according to the authors, mainly deals with affect. Intercultural awareness is based on cognition and is a pre-condition for intercultural sensitivity. Intercultrual sensitivity then can lead to intercultural competence, i.e. appropriate behavior.

Intercultural awareness -> Intercultural sensitivity -> Intercultural behavior

In that sense, “intercultural sensitivity can be conceptualized as "an individual's ability to develop a positive emotion towards understanding and appreciating cultural difference that promotes appropriate and effective behavior in intercultural communication"” (Chen and Starosta, 1997:5). That definition implies that an interculturally sensitive persons “must have a desire to motivate themselves to understand, appreciate, and accept differences among cultures, and to produce a positive outcome form intercultural interactions.”

Cultural development

Cultural development theories understand cultural competence as something that has to be developed in stages. Most often the stages include at early stages cultural knowledge and awareness, followed by cultural sensitivity and ending with cultural competency as "knowing in action".

Wells (2000), [15] summarizes several models and then presents her own that we shall present below.

The Cultural Competence Continuum (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, and Isaac, 1989) includes six stages ranging from cultural destructiveness (attitudes and behaviors that have a damaging or destructive effect on people of other cultures) to cultural proficiency (extension of cultural competence to professional practice, teaching, and research). These stages have been summarized in Stages and Levels of Cultural Competency Development[16] as follows:

- Destructiveness: Attitudes, policies and practices destructive to other cultures; purposeful destruction and dehumanization of other cultures; assumption of cultural superiority; eradication of other cultures; or exploitation by dominant groups. The complete erosion of one's culture by contact with another is rare in today's society.

- Incapacity: Unintentional cultural destructiveness; a biased system, with a paternal attitude toward other groups; ignorance, fear of other groups and cultures; or discriminatory practices, lowering expectations and devaluing of groups.

- Blindness: The philosophy of being unbiased; the belief that culture, class or color makes no difference, and that traditionally used approaches are universally applicable; a well-intentioned philosophy, but still an ethnocentric approach.

- Pre-Competence: The realization of weaknesses in working with other cultures;implementation of training, assessment of needs, and use of diversity criteria when hired; desire for inclusion, commitment to civil rights; includes the danger of a false sense of accomplishment and tokenism.

- Competence: Acceptance and respect for differences; continual assessment of sensitivity to other cultures; expansion of knowledge; and hiring a diverse and unbiased staff.

- Proficiency: Cultures are held in high esteem; constant development of new approaches; seeking to add to knowledge base; advocates for cultural competency with all systems and organizations.

The Cultural Sophistication Framework (Orlandi, 1992) has three stages: cultural incompetence, cultural sensitivity, and cultural competence. Each stage consists of four dimensions: cognitive, affective, skills, and overall effect.

The Cultural Competent Model of Care (Campinha-Bacote, Yahle, and Langenkamp, 1996) is process oriented and includes cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, and cultural encounter.

Her own CDM model, applied to the health domain, includes six stages and includes a cognitive phase and an affective phase.

| Cognitive Phase | Affective Phase | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Incompetence | Cultural Knowledge | Cultural Awareness | Cultural Sensitivity | Cultural Competence | Cultural Proficiency | |

| A lack of knowledge of the cultural implications of health behavior | Learning the elements of culture and their role in shaping and defining health behavior | Recognizing and understanding the cultural implications of health behavior | The integration of cultural knowledge and awareness into individual and institutional behavior | The routine application of culturally appropriate health care interventions and practices | The integration of cultural competence into the culture of the organization and into professional practice, teaching, and research. Mastery of the cognitive and affective phases of cultural development. | |

Wells (200), [15] argues that “cultural awareness, cultural sensitivity, and cultural competence do not achieve the level of cultural development necessary to meet the health care needs of a diverse population” and she defines barriers to cultural development: “The primary barrier to progression, ultimately change toward cultural proficiency, is the unwillingness of individuals and institutions to unearth, examine, and shed light on their underlying assumptions about people whose cultures differ from their own. These underlying assumptions are often undiscussed, unconscious, and unexamined. However, they define, shape, and prescribe individual and organizational behavior in relation to cultural diversity (Thomas, 1991)[17].”

In more simple terms, she seems to argue that learning about other cultures and appropriate behavior does not automatically lead to transfer to practice (behavioural change). A main strategy to achieve cultural proficiency is more practice under mentorship of someone that is culturally proficient.

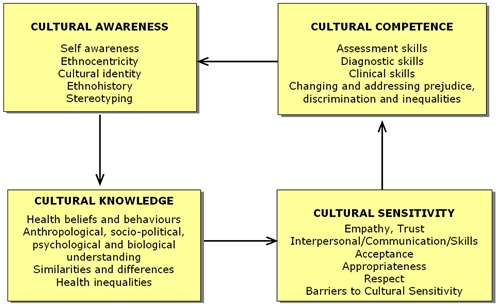

Papadopoulos, Tilki and Taylor (1988) proposed a similar model, also for the health care area [18] Model for Developing Cultural Competence.

This model for Developing Cultural Competence comprises four stages. The description below is adapted and shortened from IENE project, retrieved March 16 2016)

- The first stage is cultural awareness, which begins with an examination of our personal value base and beliefs.

- Cultural knowledge is the second stage and can be gained in a number of ways. Meaningful contact with people from different ethnic groups can enhance knowledge around their beliefs and behaviours as well as raise understanding around the problems they face. In addition one could read sociological or anthropological studies.

- The third stage is achieving cultural sensitivity, i.e. how people are viewed. Dalrymple and Burke (1995) [19] have stated that unless clients are considered as true partners, culturally sensitive care is not being achieved. Equal partnerships involve trust, acceptance and respect as well as facilitation and negotiation.

- The fourth stage, cultural competence requires the synthesis and application of previously gained awareness, knowledge and sensitivity. Further focus is given to practical skills such as assessment of needs, clinical diagnosis and other caring skills.

Cultural adjustment and culture shock

Authors investigating adjustement and "culture shock" and suggest a model where development is not linear progress.

Berado (2012), [20] defines four R's of culture change, cultural adjustment model that identifies five key changes: routines, reactions, roles, relationships and reflections about oneself that we face when we move across cultures.

- Routines are different for many things

- Reactions one receives for doing something can change. Ways people work and interact are different.

- One's roles in a different culture are not the same (e.g. being a "foreigner")

- Relationships will change, firstly with expats but then there will be new and new types of relationships

- Reflections about oneself change as certain habits are picked up or we start thinking explicitly vlaues (evolving and devolving)

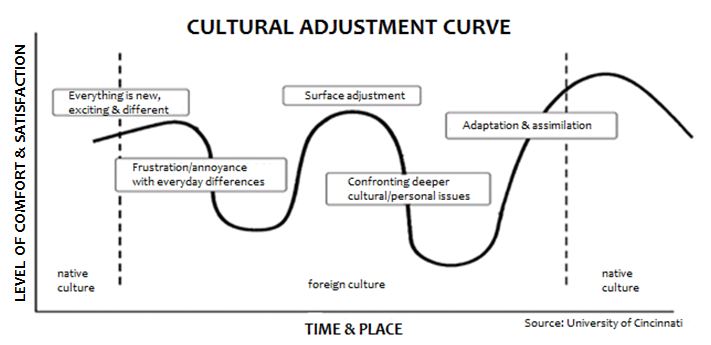

Lysgaard (1995)[21] defined a U-curve model: Honeymoon, culture shock, recovery and adjustment. Black and Mendenhall (1991) [22] argue that the U-curve adjustment model may not be universal. Pedersen, in the five stages of culture shock [23] presented a similar model: honeymoon stage, disintegration stage, reintegration stage, autonomy stage and interdependence stage.

As a practical example we reproduce a "W-curve" found in a culture shock page made for "study abroad" students.

Mark et al. (1999) [24] identify a number of psychosocial barriers to developing social competence in a different culture, including lack of coaching and practice opportunities, cross-cultural interpersonal anxiety, threat to the newcomers original cultural identity, and various personal factors.

Cultural and cross-cultural psychology

Triandis (1996:abstract) [25] “An examination of a range of definitions of culture indicates that almost all researchers agree that culture is reflected in shared cognitions, standard operating procedures, and unexamined assumptions. Cultural syndromes consist of shared shared attitudes, beliefs, norms, role and self definitions, and values of members of each culture that are organized around a theme.”

Cultural psychology, after the rise of cognitivism, seems to have become a somewhat forgotten science (Allolio-Näcke, 2005)[26]. On the other hand, cultural dimensions are central to ethnology, anthropology, (cognitive) linguistics, literature critique, etc., i.e. disciplines that put emphasis on "sense" and "meaning".

According to Doris Weidemann (2001)[27] , “investigation of intercultural interactions has demonstrated that individual psychological processes show distinct cultural patterns and, more important, that communication across cultural gaps often meets with difficulties.” She also adds, that “Communication across cultural divides is usually described as difficult and often results in misunderstandings and failure to achieve individual or even common goals. This is especially true for persons transferring to a different cultural context, as overseas students, expatriate managers or immigrants do, and adaptation to the new cultural environment can be frustrating and painful.”

In that context, literacies (not just cultural ones) cannot be compared in an abstract way or with respect to one culture, but rather as a predictor for a successful life in a given culture. This principle applies for example when comparing school systems. “Nur in dem Falle, "dass innerhalb eines jeden Landes, die erfassten Kompetenzen zur Vorhersage einer erfolgreichen Lebensführung beitragen", könnte das literacy-Konzept als tertium comparationis fungieren. In vielen Ländern aber spielt es keine bzw. nur eine untergeordnete Rolle, so dass "der Ausgang einer solchen Validitätsprüfung wahrscheinlich zu einer kulturellen Gruppierung der Funktionalität der Grundkompetenzen führen wird";” (Hermann-Günter Hesse, cited by Allolio-Näcke, 2005).

Cultural intelligence

Cultural intelligence (Ang & Van Dyne: 2008; Livermore: 2009)[28] [29] seems to be a way of defining cross-cultural competence and is developed in the business and military community. In business, it also is known as cultural quotient (CQ) in analogy to the Intelligent quotient (IQ). It is the ability to cope with other cultures.

Ang et al. (2007) [30] define a cultural competence/Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS). Their definition of cross-cultural compentence includes four dimensions: "(1)Metacognitive CQ — conscious cultural awareness during intercultural interactions, (2) Cognitive CQ — knowledge of cultural norms, practices, and conventions, (3) Motivational CQ — attention and energy toward cultural differences, and (4) Behavioral CQ - ability to act appropriately during intercultural interactions in terms of verbal and nonverbal behavior (Cronbach's alpha = .88, .91, .84, and .88 respectively). Higher scores indicate greater CQ on each subscale." (Goldstein & Keller: 2015)

Earley and Mosakowsky (2004) define cultural intelligence [31] as someone's “natural ability to interpret someone's unfamiliar and ambiguous gestures in just the way that person's compatriots and colleagues would, even to mirror them.”. The authors distinguish three components: Cognitive CQ (head), Physical CQ (body) and Emotional/motivational CQ (heart).

Cultural intelligence seems to be natural to some people but can be effectively trained and measured, e.g. Earley and Mosakowsky suggest six steps. The first step is using Cultural competence/cultural intelligence self-assessment instrument that includes 12 items. This instrument also allowed identifying six different profiles:

- the provincial: effective in his original environment, cannot adjust to other cultures

- The analyst: “methodically deciphers a foreign culture’s rules and expectations by resorting to a variety of elaborate learning strategies.”

- The natural: relies entirely on his intuition rather than on a systematic learning style.

- The ambassador, the most common type among international managers, can make believe that he "belongs" but understands his/her limits.

- The mimic “has a high degree of control over his actions and behavior, if not a great deal of insight into the significance of the cultural cues he picks up.”

- The chameleon “possesses high levels of all three CQ components and is a very uncommon managerial type.”

Workplace diversity and international business

See also other sections, in particular the ones about assessment.

Simple models of cultural difference

Models of cultural difference are popular in management and management education since corporations do have to deal with different cultures.

Triadis (1966

Triadis [32] , worked on "cultural syndroms". These are defined as patterns of of shared attitudes, beliefs, categorizations, self-definitions, norms, role definitions, and values that is organized around a theme that can be identified among those who speak a particular language, during a specific historic period, and in a definable geographic region. Examples identified in the 1966 article are:

- Tightness: Some cultures have many norms that are tightly applied as opposed to those who have few norms and that are loosely applied. Norms are situational, i.e. applied to certain domains, however, there also is an overall density of norms

- Cultural complexity: The number of different cultural elements can vary a lot, e.g. hunters and gatherers identify 20 "job" roles and information societies have hundreds of thousands.

- Active-passive: first described by Diaz-Guerrero (1967), “includes a number of active (e.g., competition, action, and self-fulfillment) and passive (e.g., reflective thought, leave the initiative to others, and cooperation) elements.”

- Collectivism: The self is described as an aspect of a collective entity and personal goals are subordinated to collective goals. Social behavior is ruled by norms, duties and obligations.

- Individualism: “The self is defined as independent and autonomous from collectives. Personal goals are given priority over the goals of collectives”

- Vertical and horizontal relationships: In some cultures hierarchy is very important, including within groups.

At the time of writing, Triadis, stated that “The number of syndromes for an adequate description of cultural differences is at this time unknown. It s hoped that a dozen or a score of syndromes, to be identified in the future, will account for most of the interesting, reliable cultural differences. There is also the problem that syndromes are somewhat related to each other. For example, tight, passive, simple cultures are likely to be more collectivist; loose, active, complex cultures are likely to be more individualistic. The higher these correlations, the less does any one syndrome provide independent information about cultural differences”. “Collectivism is maximal when a society is low in complexity and tight; individualism is maximal when a society is complex and loose” (p. 412)

Syndroms like individualism and collectivism can be defined by underlying attributes. Triadis (1995) suggests the meaning of self, the structure of goals, the function of norms and attributes to define behaviour, focus on the needs of the ingroup or social exchange. Moreover he identified about 60 attributes in total found in collectivist of individualist cultures.

Individualism and collectivism are relative and manifest in all cultures. In addition these traits appear combined with horizontalism and verticalism. {{quotation|Tt is possible to identify attitude items that measure horizontal-vertical, collectivism-individualism (Singelis,Triandis, Bhawuk, & Gelfand, 1995). “The use of a particular pattern is likely to be culture-specific. Thus, in a specific culture, in some situations, people will be vertical collectivists (VC), in others, vertical individualists (VI); in some situations people may be horizontal collectivists (HC), and in others, horizontal individualists (HI).” From these tendencies one can construct profiles and distribution of scores within a culture could define it.

Hampden Turner and Trompenaars (1993)

According to Darlene Brannigan Smith et al. in the Seven Cultures of Capitalism, Hampden Turner and Trompenaars (1993:11) suggest that different countries champion different value propositions for creating effective organization.

- Universalism (call for universally applicable law and order) vs. particularism (allow for personal indulgence and idiosyncrasies),

- anlyzing (demand for facts and attention purely on the bottom line) vs. integrating (viewing everything within the context),

- individualism (applaud individuals for singular performance) vs. communitarianism (organization, groups and community above else),

- inner directed (self-starter) vs. outer-directed (approaching groupthink) orientation,

- time as sequence (time is money) vs. time as synchronization (all for one),

- achieved status (working hard to achieve) vs. ascribed status (status because of power), and

- equality (all get an even break) vs. hierarchy (some people are more important because of their hierarchical authority).

Inglehart and Welzel

Inglehart and Welzel identify two major dimensions of cross cultural variation in the world:

- Traditional values versus Secular-rational values and

- Survival values versus Self-expression values.

Using data from the World values survey, the authors created a well-known cultural map of the world where positions with respect to these two dimensions are overlayed with "nominal" criteria (e.g. religion, or geography). The map below is a modified version of the original made for Wikipedia by an unknown author.

Hofstede

Hofstede distinguishes five or six dimensions of national cultures. Each of these is defined by a list of criteria. Hofstede (2011) [33], summaries these dimensions:

1. Power Distance, related to the different solutions to the basic problem of human inequality;

2. Uncertainty Avoidance, related to the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future;

3. Individualism versus Collectivism, related to the integration of individuals into primary groups;

4. Masculinity versus Femininity, related to the division of emotional roles between women and men;

5. Long Term versus Short Term Orientation, related to the choice of focus for people's efforts: the future or the present and past.

6. Indulgence versus Restraint, related to the gratification versus control of basic human desires related to enjoying life.Wikipedia, based on Hofstede (2011) [33] provides a nice summary.

National cultures are not identical to organizational or individual cultures. E.g. within a same town one can find companies that adopt a very different organizational-cultural model. The same is true for individuals. However, national (or even supra-national) cultures doe influence organizational and individual ones.

Instruments to measure cultural diversity and competence of individuals

There exist both quantitative and qualitative instruments. These instruments were created to learn about people's representations and not to assess cultural competence (whatever that means). Many researchers seems to agree that (at least for now) measuring cultural competence requires a mixed methods approach. Below we shall describe a few instruments that allow observing and systematizing cultures.

World Values Survey

According to Wikipedia, “The World Values Survey (WVS) is a global research project that explores people’s values and beliefs, how they change over time and what social and political impact they have. It is carried out by a worldwide network of social scientists who, since 1981, have conducted representative national surveys in almost 100 countries. The WVS measures, monitors and analyzes: support for democracy, tolerance of foreigners and ethnic minorities, support for gender equality, the role of religion and changing levels of religiosity, the impact of globalization, attitudes toward the environment, work, family, politics, national identity, culture, diversity, insecurity, and subjective well-being.”

The WVS started in 1981 and is now governed by the World Values Survey Association, based in Stockholm. The 6th wave started in 2008 and was finished in 2014, and the 7th is planned for 2017-2018.

Structure Formation Technique

Structure formation technique is a qualitative method that attemps to elicit representation structures.

Weideman's (2001) [34] study focuses on subjective theories hold by German Immigrants in Taiwan and that can be verbally explicated and reconstructed by way of dialogue between researcher and participant. The research method goes through the following steps:

- A semi-standardized interview that will try to elicit the contents of the subjective theories

- A visualization of the theory structure ,using representational rules of the Heidelberg structure formation technique, (Heidelberger Strukturlegetechnik, SCHEELE & GROEBEN, 1988)

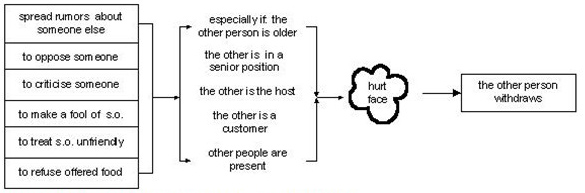

Based on this Heidelberg structure formation technique, she developed a set of interview questions and rules for representing the theory.: “a differentiation was made according to the outcome of actions (face gained or face lost) and the person concerned (self or other).” The combination of these two dimensions will define four semantic fields, namely a) to lose face, b) to gain face, c) to hurt the other person's face, d) to give the other person face.

Results then can be represented graphically, for example like this:

Arts-Informed Research

Arts-informed research uses artistic productions to elicit representations.

Over the last decade, a growing number of social scientists have become interested in visual methodologies. On could distinguish between "researcher created", "respondent generated" and "found" visual data. Visual arts can be found in all three. [35]

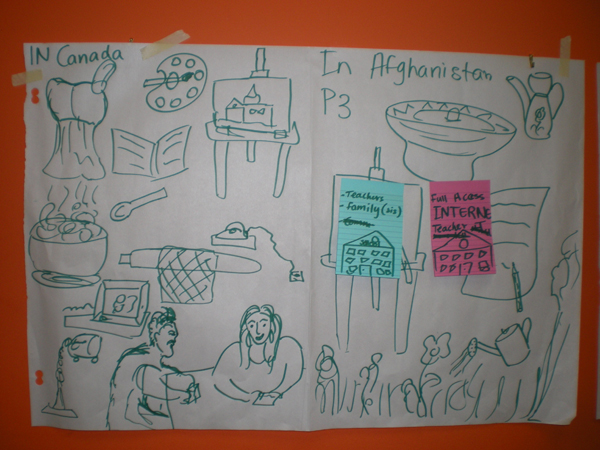

Guruge et al. (2015) [36] describe an arts-informed technique “to understand the changes in refugee youth's roles and responsibilities in the family within the (re)settlement context in Canada. The study involved 57 newcomer youths from Afghan, Karen, or Sudanese communities in Toronto, who had come to Canada as refugees. The data collection method embedded a drawing activity within focus group discussions.”

This study also included eight refugee youth peer researchers from the three communities. In line with community-based participatory research principles, {{quotation|Peer researchers received three months of research training and were actively involved in paid capacity in all phases of the study, including research design, data collection, data analysis, and writing. Guruge et al. (2015:[14]) describe the elicitation process as follows:

Each participant was invited to draw two pictures:

- one depicting pre-migration roles and responsibilities,

- and the second depicting post-migration roles and responsibilities.

A key lesson learnt was that adequate time and opportunities must be given to participants to (1) create the drawings, (2) to interpret and discuss the drawings and (3) to complete or change the drawings as a result of group discussions. Facilitators must attempt to clarify and expand links between drawings and discussions.

According to the authors [paragraph 38], “The multiple data collection methods (i.e., drawings and individual reflections on them, and focus group discussions) we used in this study were complementary: the drawings provided unique insights into certain aspects of their lives. For example, the magnitude of the difference in youth's (built and natural) environments came up in the drawings that were not discussed in the focus groups. The sense of cohesion versus scattered and chaotic patterns in the drawings is also interesting. On the other hand, the focus group discussions provided unique information on other aspects of their lives, such as racism. In addition, the drawings also provided more contextual information that enriched the understanding gained from the focus groups.”

Data analysis and interpretation involved several levels of analysis and was based on participant's own explanations:

- a reflective dialogue between each participant and his own drawing

- a group dialogue concerning all the drawings of the group

- reflections of the peer (refugee youth) researchers from each group in response to questions about (1) and (2) from the rest of the research team

- the research teams reflections across the three groups

A list of themes and supporting excerpts was finally established in the form of a table.

Somewhat similar research was conducted by Frey and Cross (2011) [37] on overcoming poor youth stigmatization and invisibility through art. Initially, a more traditional plan was to conduct interviews with various stakeholders, then creating focus groups, and finally a joint work on a common video to trigger dialogue with other actors. The team then found out the dramatization and video could (and did) have a more important role “We discovered that the inclusion of dramatization and video had three main effects: first, they favored the involvement of the young men and women; second, they allowed them to share their experiences, formerly blocked by stigmatization processes; third, they were a potent instrument to make their perspectives visible to other social actors concerned by this problematic (teachers, government officers, parents).” Frey and Cross (2011:69)

Tristan Bruslé's (2010) [38] research examines the place that Nepalese immigrant workers occupy in Qatar. Visual images, mainly photographs, are use as one of the research tools to illustrate the divided nature of society.

“I have tried to put forward the hypothesis that photographs are not just an illustration, but that social realities can indeed be understood through pictures. The building of places, from collective spaces to very private ones, clearly stands out in the pictures. The use of pictures to analyze social and spatial division in Qatar has enabled me to grasp some realities that I had either overlooked or not fully understood. While carrying out fieldwork, and particularly new fieldwork, the researcher is continually bombarded with a flow of information, making it at times difficult to focus on everything of interest. Pictures are therefore a way of focusing on detail, especially in a migrant's room, which might not necessarily have been studied while talking to migrants. Looking at pictures taken in an almost random way is also a way of reactivating one's memory. Distant places, emotions and memories come to life when perusing pictures. Things that were not first noticed when the photograph was actually taken, but were "discovered" thanks to a careful study and comparison of pictures, come across as important and make sense. A juxtaposition of scenes has helped me identify common points between places. Moreover, pictures have helped me show the different levels of spatial segregation, from the town to the migrant's bed. Images of walls and of physical separation may prove to be speaker louder than mere words in making the reader realize what segregation really is. Indeed, pictures can play the role of backing up research and be a valuable tool in that they convey large amounts of information that would sometimes be harder to explain verbally.” (Bruslé's, 2010, [29])

Map making

Having individuals draw maps of their environments can help to understand how their environment is structures in terms of various opportunities and social relations.

Olga den Besten (2010) [39] studied social and spatial divisions (urban segregation). Her study “explores children's and young people's experiences in two socially contrasted neighbourhoods in Berlin through subjective maps drawn by the children.”

“Children were asked to produce two maps: first, to draw their way home from school and all the objects that attracted their attention on the way. This task was chosen because all the children went to school, so the way home from school was their everyday, routine trajectory (see also ROSS, 2007). Coming back home from school was chosen because of the supposedly more relaxed, unhurried character of this trajectory and more opportunities for deviations from this way, like, for example, popping in to shops or playing in a park after classes. Second, the children were asked to draw their "neighbourhood" or "territory", i.e. a city area which they knew rather well and where they "felt at home". This drawing activity was done at school during one lesson.” (den Besten: 2010: [13]).

In addition, children were asked to place four types of emoticons on the maps: (1) A heart symbol to mark places they like, (2) a big dot for places where they hang out, (3) a cross inside a circle for places they disliked and (4) a square for places they fear.

Results showed that the children's socio-spatial worlds were different in the two segregated areas of the city. Generally, drawings from children of the advantaged area are comparatively more elaborated, show a larger space, more places for activities, a denser network of friends, and so forth. This also reflects the situation that advantaged children have more access to extra curricular activities and therefore for personal development.

A map of her "subjective territory" by a 13-year-old German-American girl from the school in Zehlendorf. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[39]

Drawing 3a (by a Turkish boy aged 14 in Kreuzberg) features a youth club and a football field. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[39]

Instruments to measure cultural competence of organization and its members

The following tools rather focus on organizations and are mostly self-evaluation tools to help reshape their policies and training. Overall, there roughly seem to be three types of individual competences:

- The competence to understand oneself

- The competence to understand another culture

- The competence to intervene

Cultural competence self-assessment questionnaire

The Cultural competence self-assessment questionnaire (CCSAQ) Mason (1995), [40] is designed to help health agencies cope with cultural difference, i.e. to assess their need for cultural competence training.

“In response to the growing body of literature promoting culturally competent systems of care, the Portland Research and Training Center developed the Cultural Competence Self-Assessment Questionnaire (CCSAQ). The CCSAQ is based on the Child and Adolescent Service System Program (CASSP) Cultural Competence Model (Cross, et al., 1989). This model describes competency in terms of four dimensions: attitude, practice, policy, and structure. The instrument helps child- and family-serving agencies assess their cross-cultural strengths and weaknesses in order to design specific training activities or interventions that promote greater competence across cultures” (Mason: 1995).

This manual publishes two variants of the questionnaire. One for assessing cultural competence training needs of mental health and human service professionals and the other to assess cultural competence training needs of human services organizations and staff.

TOCAR Collaborative Campus and Community Climate Survey for Students

The TOCAR Collaborative Campus and Community Climate Survey forStudents includes 25 questions and was made by Training Our Campuses Against Racism' (TOCAR) chapters at North Dakota State University, Concordia College, Minnesota State Community and Technical College, and Minnesota State University Moorhead.

The Culturual Competence Assessment Tool (CCAT)

The Cultural Competence Assessment Tool (CCAT), made by the Boston Public Health Commission is an answer to the 2001 United States Department of Health and Human Services Office ofMinority Health (OMH) issued National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care (CLAS).

“The Cultural Competence Assessment Tool (CCAT) contains three sections – each focuses on a key component in the provision of culturally competent health care. [...] The first section of the tool assesses organizational cultural competence in health care leadership, staffing, and community involvement. The second section assesses cultural competence in the institution’s delivery of health care. The third section assesses cross-cultural communication at the institution” (Cultural Competence Assessment Tool).

Cultural competence Checklist: Personal reflection

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2010) [41] created a one-page checklist that was developed to “o heighten your awareness of how you view clients/patients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) populations.”

Quality and culture quiz

Quality and Culture Quiz is a self-evaluation quiz that targets members of the health community.

The Cultural and Linguistic Competence Family Organization Assessment (CLCFOA)

Made by the National Center for Cultural Competence, the The Cultural and Linguistic Competence Family Organization Assessment (CLCFPA) survey was made to help family organizations concerned with children and youth disorders and disabilities. It requires approximately 20-30 minutes to complete. It consists of four sections: Our World View, Who We Are, What We Do, and How We Work. As several others of its kind, this survey helps to identify an organizational culture.

Teaching cultural competence

Teaching cultural competence is addressed in many different ways and for different purposes and appears under different names, e.g. cultural competence training, cross-cultural competence training, transcultural competence training, intercultural competence training, cultural diversity training, cultural intelligence training, cross-cultural training, etc.

According to Chen and Starosta (1997), [14], intercultural training programs include "T-groups," critical incidents, case studies, role playing, and cultural orientation programs.

Cultural competence education aims to help people build relations and also work on attitudes and knowledge. In the literature, there seems to an emphasis on "learning how to learn", "becoming open-minded", etc. as opposed to learning measurable traits. For example, a meta study by Beach et al. (2005) [42] shows that “Cultural competence training shows promise as a strategy for improving the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals. However, evidence that it improves patient adherence to therapy, health outcomes, and equity of services across racial and ethnic groups is lacking. Future research should focus on these outcomes and should determine which teaching methods and content are most effective.” That being said, we believe that acquiring such rather metacognitive skills does require some knowledge, attitudes and skills bases.

A lot of the research and practical literature concerns the three areas we identified already: Health, international business and higher education.

- In business, there seems to be a focus on acquiring "cultural intelligence" or at least improve over some "baseline test". The goal is become a good negotiator or a good manager that has sufficient insight into another culture to behave efficiently and appropriately.

- In the health sector, there is more emphasis on changing the whole mindset of health personnel and organizations. “Three major conceptual approaches have emerged for teaching cultural competence, focusing on knowledge, attitudes, and skills, respectively” (Betancourt (2003)[43] cited by Kripalani (2006) [44]

- In higher education, there is emphasis on preparing students for studies abroad or receiving students. Other concerns are dealing with (marginalized) minorities or running international campuses or franchises.

Determining how cultural competence should be taught also requires understanding how it is learning. Since cultural competence is a complex soft still that involves knowledge, attitudes, skills and problem solving skills, this ain't easy.

Cultural competence can be addressed at the individual, a the organizational, or at the system level. While individuals are concerned by any of these levels, organizational and societal learning requires other kinds of changes, e.g. rules.

A large number of training classes or training materials (e.g. The Cultural Competence Education Resource Toolkit that includes 23 tools.

General principles

Deborah Corder and Alice U-Mackey (2015) [45] argue that educating intercultural literacy is very challenging. Cognitive aims (e.g. learners being able to pass an exam) can be met, however, meeting affective and behavioral goals might be much more difficult. According to the authors, “research shows that the development of IC is a complex process that involves cognitive, metacognitive, affective and behavioural development, and has to be intentionally developed over time (Ehrenreich 2006; Stier 2006; Crossman 2011; Deardorff 2011). As Perry and Southwell (2011) and Witte (2011) point out, there is increasing evidence that the normal classroom or lecture context with a cognitive orientation alone cannot provide the environment for learners to develop the necessary competencies. Nor will IC automatically develop by just encountering other cultures whether in the classroom, through study abroad, overseas holidays, the workplace or social settings.”

Intercultural diversity is an important component of global citizenship. Vadura (2007: 17) argues that “The knowledge, skills and values that international studies graduates gain need now more than ever to reflect understanding of social responsibility and cultural inclusivity, embodied in the concept of global citizenship.”

Johanna E. Crossman led a qualitative study that aimed to “discover how undergraduate and culturally diverse students experienced a collaborative, international, online, experiential project to learn about intercultural communication. Student participants in the study endorsed experiential learning in culturally diverse groups about intercultural communication through intercultural communication.”. The study involved students from Australia, international students from Asia (in Australia) and students from the Netherlands. The task was to “to respond to a case study that concerned a franchisor in Australia considering two expressions of interest from potential franchisees in the Netherlands and Hong Kong.”. More specificially, members of the these three populations were required to act as "communication consultants" to advise the fanchisor of any potential intercultrual communication implications between the Australian organisation and the Dutch and Asian franchise. In other words, each type of student had to play and reflect upon his own cultural inheritage.

In this context, the author found that “learning about intercultural communication through intercultural communication is a powerful activity that responds to the need for learning approaches that internationalise the business curriculum in universities and develop global citizenship. The capacity of the experiential project appeared to engage students in ways that seemed to be perceived as authentic and relevant to their lives and work. The study has also illuminated how participants try to make sense of intercultural communication by juxtaposing personal experience with theoretical literature. Whilst stereotyping did occur, the observation can be used in the design of future activities so that the potential for meta-cognitive approaches can be developed further through asking questions about what stereotyping is and how, why and under what circumstances individuals might engage in it, particularly when tension and conflict exists in intercultural communication and indeed, culturally diverse learning contexts.”

Cultural competence education probably has to be adapted to different contexts, e.g. training health personnel to deal with persons from different cultural background is not the same as training international managers since heir activities and foci are different. However, there exist probably some first principles: Kriplani et al. (2006) within their prescriptions of cultural competence in medical education, argue, that practical skills must be taught as opposed to just general principle meaning that a practitioner has to learn to “listen to the patient's perception of the problem, explain their own opinion, acknowledge and discuss differences and similarities, recommend treatment, and negotiate an agreement”. They also recommend interactive Educational Methods, such as Standardized Patient encounters, role-play, and Self-reflective Journal Assignments. These should be reinforced through direct faculty observation and feedback. Cultural competence should be taught throughout the clinical education as opposed to specialized workshops. We believe that these principles that we could summarize as "learning in action in authentic contexts" could be applied to other settings.

Cross-cultural training

According to Rita Bennet at al. (2000:241), [46] there are three reasons for cross-cultural training (CCT): “(1) manage change — personal-professional transition; (2) manage the cultural differences; and (3) manage their professional responsibilities”. According to the same authors, for an international assignment to be succesful, the whole family should be trained since it can act as support unit.

Contents for cross-cultural training should include at least the following topics: General and country-specific cultural awareness; Area studies, history, geography, poli- tics, economics; Frameworks for understanding and valuing cultural differences; Planning for a successful international assignment; Intercultural business skills for working effectively in the local environment; Understanding cultural variations for those with regional responsibilities; Business and social customs in the host country; International transition and stress management; Practical approaches to culture-shock management and lifestyle adjustment; Information on daily living issues; Special issues: partners and families abroad; Repatriation as a predeparture issue.

The training design should comply with adult education principles and it should include both didactic and experiential approaches. Bennet et al. (2000) also not that “research indicates that an “integrated program model” delivers the most effective training (Copeland & Griggs, 1993; Black & Mendenhall, 1990,Rhinesmith, 1993). An integrative model works through the complex web of factors impacting assignees. In fact, training may be a misnomer for this process, which is as much about change management as it is about education. Cross- cultural training not only targets practical, logistical considerations but intellectual and psychosocial dimensions as well.”

Cultural intelligence training

Cultural intelligence training seems to have the same purpose as cross-cultural training, i.e. it just may name a different sub-culture working in cultural competence training for organizations. In addition, cultural intelligence training is also concerned by different organizational cultures within a given national culture.

According to a Harward Business Review article [31], managers can be socially intelligent in their own settings but ineffective in culturally novel ones. That means they do not lack so-called "emotional intelligence", but are "cross-culturally" challenged.

Early and Mosakowski provide the following advice: Rote learning about foreign beliefs and customs is useful, but will not prepare a person for every situation that will arrise. Instead, managers should learn how to learn in all (of their) three Cognitive Intelligence (CQ) dimensions:

- Cognitive CQ (head): Look for consistencies in the other's behavior. Example: "they were all punctual, deadline-oriented, and tolerant of unconventional advertising messages"

- Physical CQ: Adopt (or cope with) the others' physical behavior, e.g. in France, allow to be kissed on you cheeks, or in the USA do not move in too close.

- Emotional/motivational CQ (heart): Overcome failures, after confronting obstacles, setbacks, or even failure, reengage with greater vigor.

These example could imply that training needs to present learners with situation that forces them to abstract principles from observed clues.

Early and Mosakowski then present a six stage self-learning model "Cultivating Your Cultural Intelligence" that applies both to foreign culture and different enterprise cultures.

(1) Examine the Cultural intelligence quotient (CQ), e.g. using their instrument

(2) Selects training that focuses on weaknesses. For example, persons with a lack of cognitive CQ could read case studies and try to distill their common principles.

(3) The general principle from above then must be applied in real situations, e.g. greeting someone correctly or finding out where to buy a newspaper.

(4) Organizes personal resources to support a chosen approach. In particular find time, schedule and persons in the organization to conduct the training

(5) Enter the cultural setting and base coordination and plans with others on identified strength (see six profiles above)

(6) Evaluate the outcomes, e.g. with the help of a focus group.

The question now, is how to translate this model into a more formal training setting. A mixture of case study and role playing probably could be appropriate.

Livermoore (2010) suggest to engage actively within a foreign culture, e.g. read local newspapers, go to movies and museums, eat out, learn the language, attend cultural celebrations, visit a temple, mosque or church, join a multicultural group, find a cultural coach, take a class.

Cultural competence training

Cultural competence training is a term that is often used in the health sector. According to Long (2012) [47] “Despite the challenges and inconclusive results of previous studies, cultural competence can be taught and learned. Asystemic review of cultural competence training interventions for health care providers concluded that indeed training did influence provider knowledge, attitude and skills (Beach, et al 2004; Beach 2005, Brach & Fisher, 2000).”

Mary C. Beach et al. (2005) [42] in her literature review and analysis of Health Care Provider Educational Interventions, found evidence “that cultural competence training improves the knowledge of health professionals (17 of 19 studies demonstrated a beneficial effect), and good evidence that cultural competence training improves the attitudes and skills of health professionals (21 of 25 studies evaluating attitudes demonstrated a beneficial effect and 14 of 14 studies evaluating skills demonstrated a beneficial effect). There is good evidence that cultural competence training impacts patient satisfaction (3 of 3 studies demonstrated a beneficial effect) [...]”. Contents of the intervention include either general concepts, specific cultures or both. Teaching strategies were either experiential or not. As in cross-cultural training in business, “all cultural competence interventions should target the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals, so measurement of these intermediate outcomes are appropriate, and results are encouraging.”

Interestingly, Beach et al (2005) mention that “concerns have existed about whether specific cultural information taught in curricula using a knowledge-based, categorical approach might promote stereotyping of patients”. The indeed found that in study, “following an intervention that taught specific cultural information, students were more likely to believe that Aboriginal people were all alike” and recommend that a patient-centered approach should be emphasized that takes into account understanding general concepts of "culture".

Beach et al. don't provide details about the educational designs, but noted that all types of interventions were reported to be successful.

Cultural competence learning is most often described as a set of competences to be acquired or as a set of components, but also as developmental model, i.e. various authors define various stages. In Bhui et al (2007) review of cultural competence in mental health care, “only three studies published their teaching and learning methods”. One model of cultural competency recommended participant observation, analysis of case reports, consultation and conferences around specific clinical problems [48]. Another [49] recommended discussing and writing about case histories and paying attention to the narratives. A model for nursing working in critical care settings [50] deployed interactive lectures and small group teaching with role-play exercises and patient centred interviews to enhance cultural understanding.

The cultural development model

Marcia (2000) [15] presents a cultural development model (CDM) that summarizes other models,

Lay theories

Before teaching intercultural competence, it may be interesting to see how people view cultural difficulties. Goldstein and Keller (2015) [51] analyzed U.S. college students’ lay theories of culture shock. Results show that “Students’ beliefs differ significantly from those of intercultural experts. In contrast to the A, B, C model of culture shock which represents the scope of academic theories across affective, behavioral, and cognitive domains, college students’ lay theories emphasize the behavioral, or culture learning, approach over affective and cognitive components of culture shock. [..] Although some of the minimally endorsed internal causes of culture shock deserve such a rating (for example, the outdated and unsubstantiated notion that culture shock is due to emotional instability), other low rated causes warrant greater attention from potential sojourners, including those involving stress management, social support, identity confusion, and prejudice.” (Goldstein & Keller, 2015).

Strategies and tactics for cultural competence education

Strategies and tactics in competence training and education differs from context to context.

International assignments

Bennet al. (2000), in the context of of CCT training for international assignments include case studies, critical incidents, simulations, videos, role plays, lectures, and guided discussions. They also emphasize that “the more tailored these methods are to the company, to the assignee and family, to the employee’s job responsibilities, and to the location, the greater the impact and learning outcomes.”

In the same perspective, Littrell, Salas (2005) [52] and Littrell et al. (2006) [53] discussed various training foci and guidelines (including pedagogical strategies and tactics) for cross-cultural training (CCT), e.g. making expatriates ready for a different culture. According to Littrell and Salas (2005:308), “Cross-cultural training can be defined as an educative process focused on promoting intercultural learning through the acquisition of behavioral, cognitive, and affective competencies required for effective interactions across diverse cultures”. They also note that this type of training focusses on attitude change rather than information acquisition. Three skills need to be developed: self-maintenance, interpersonal and cognitive. Since one cannot train someone for every situation that could be met, the individual also must be taught to engage in a continouous self-development process. That means that he must be taught meta-cognitive strategies that facilitate learning and that unexpected situations (e.g. disconfirmed expections) can be managed appropriately.

Below is a summary of typical CCT training program elements

| Focus of Training Intervention | Potential Strategies |

|---|---|

| Developing the skills required to make isomorphic attributions | Attribution training (learn to interpret behavior in a manner similar to that of host nationals) |

| Imparting the knowledge needed to understand cultural differences | Culture awareness training (better understand their own culture) |

| Assisting in the development of host-culture appropriate behaviors | Cognitive-behavior modification training (develop the habitual behaviors desired in the host culture including behaviors to avoid) |

| Promoting successful adjustment via on-the-job training | Interaction training (the experienced expatriate introduces the novice to business practices, to key people at work and within the community, and shows how to carry out daily-life tasks. |

| Developing the language skills required for everday interactions | Language training (e.g. ability to exchange common courtesies in the host language) |

| Providing the expatriate with information regarding living and working conditions | Didactic training (in particular, enable the expatriate to understand the host culture and to possess a framework within which to evaluate the new situations). |

| Giving the expatriate the opportunity to practice potential situations to be encountered in the host culture | Experiential training tactics, learning by doing, that includes see visits, role-plays, intercultural workshops, and simulation) |

The authors also point out that CCT should be tailored to both the features of the assignment and the invidual (since personality traits make a huge difference in terms of CCT needs and learning ability). CCT should use multiple educational strategies and should not stand alone.

Health

Tracy Long (2012) [54] gave an overview of teaching strategies for cultural competence in nursing students that we reproduce in part below:

- Group discussions: used for “teaching cultural competence concepts. Its advantages include the active learning process that promotes exchange of ideas however distractions and unmanaged group dynamics can be challenges”.

- Student written reports: “[..] through self directed learning modules are often used as evaluation methods for learning concepts. A disadvantage in this learning strategy is that isolated learning is productive only for certain learning styles.”

- Clinical experiences: “with real life experiences increased student comfort and confidence in caring for pa tients from diverse cultures and increased after repeated exposures to persons from other cultures (Chrisman & Maretzki 1982; 2005; Trotter, 1998).”

- Simulation:

- guest lectures

- mentoring and consultation

- educational partnerships

- lived immerson/study abroad.

| Teaching Strategy | Study | Advantages | Disadvantages | Outcomes | Methodology |

| Lecture | Linares (1989)

Bond (2001) Boyle, (2007) |

Structured Easy to organize and control for instructor | Limited interaction and feedback | Students are more comfortable in structured environments they are familiar with. Students don’t score above knowledge alone concepts. | Qualitative surveys |

| Group Discussion | Zuzelo (2010) | Interactive | Distractions from on task discussion | Students desire a reflective communication process to exchange ideas and build on each other’s thoughts. | Focus group |

| Student Written Report | Betancourt (2007) | Thorough, self directed | Isolated learning | Not measured | Qualitative |

| Assigned Readings/Module | Lee (2006) | Knowledge based | Limited to stereotyping | Improvement in knowledge of selected health beliefs and practices | Descriptive qualitative |

| Clinical Experience | Chrisman & Maretzki (1982) Trotter

(1998) Kardong (2005) |

Real life experience | Limited to availability in clinical setting | Comfort in caring for patients from diverse cultures increased after repeated exposures to persons from other cultures. | Descriptive qualitative |

| Lived Immersion | Jones and Bond (2001) Kardong (2005)

Hinck & Hope (2006) Wiegerink-Roe & Rucker- Shannon (2008) Larson (2010) |

Comprehensive from 1 week to 3 weeks to full semester | Expensive Limited to students who are willing and able to travel | Student anxiety about a different culture decreased with >1 week exposure in a study abroad experience. | Qualitative descriptive and phenomenologic studies |

| Oral Report | No studies found | Structured | Limited to effectiveness of public speaking. Emphasis may be on delivery rather than content | ||

| Journal Keeping | Jones (2000) Alpers (1996) | Thorough, self directed | Isolated learning | Reflective improvements in self awareness | Qualitative and group discussion |

| Video/ virtual experience | No studies found | Knowledge based | Limited to stereotyping | ||

| Simulation | Rutledge (2008) | Real life experience | Limited to availability in technology | ||

| Organized Field Trip | No studies found | Structured | Limited to availability | ||

| Standardized Patient | Medical School studies only | Interactive, standardized | Limited to availability Cost of actors | Increase in confidence with repetition | Studies done for medical school students |

| Service Learning | Anecdotal studies | Interactive | Short term | Students increased appreciation of a different culture | Qualitative Descriptive |

| Mentoring and Consultation | Napholz (1999)

Ranzijn (2005, 2008) |

Real life experience | Limited to availability in clinical setting | Significant improvement in knowledge of specific culture | Self report study; pre and post test after intervention and control group |

| Educational Partnerships | Jacobs (2003) | Real life experiences Collaboration within community | Limited to availability Coordination required for contacts | Improvements in attitude toward ethnic groups | Qualitative reports |

Direct instruction

Facts and simple skills learning about various aspects of a different culture

Mentoring

Mentoring, also called "interaction training" allows a novice to learn from an experienced person, typically an expatriot in a company.

Role playing

Role playing can be used for:

- attribution training, e.g. learning to interpret behavior from the viewpoint of another

Roles games

T-groups

A T-group or training group (sometimes also referred to as sensitivity-training group, human relations training group or encounter group) is a form of group training where participants themselves (typically, between eight and 15 people) learn about themselves (and about small group processes in general) through their interaction with each other. ( Wikipedia)

Cultural infusion activities

Attending cultural events

Assessment of cultural competence

Besides trying to represent, summarize, visualize and compare different cultural representations, research also attempts to quantify cultural competence with psycho-metric tools. Education, for example is interested to measure learning within a student population that takes part in an internationalization program.

According to the Sage Encylopedia of Intercultural competence (2015:18), “Most of the existing intercultural competence tools, which usually fall into the indirect-evidence category [i.e. the perception of learning by the participants themselves], consist of some sort of questionnaire or inventory. These can generally be categorized into two broad categories: (1) external: cultural difference and (2) internal: personality traits/predispositions/adaptability. Most of these rely on the respondent’s perspective as the basis of the data collecte”.

Intercultural Knowledge And Competence Value Rubric

The association fo American Colleges and Universities developed an Intercultural Knowledge And Competence Value Rubric.

The authors, citing Bennett, (2008) [56]define Intercultural Knowledge and Competence as “a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioral skills and characteristics that support effective and appropriate interaction in a variety of cultural contexts.”

“The intercultural knowledge and competence rubric suggests a systematic way to measure our capacity to identify our own cultural patterns, compare and contrast them with others, and adapt empathically and flexibly to unfamiliar ways of being”

This rubric is informed by two sources, Bennett's Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity [57] and D.K. Deardorff's intercultural framework model [58].

The rubric is reproduced here.

intercultural communication sensitivity scale

Chen and Starosta (2000) [59] developed an instrument to measure intercultural communication sensitivity. Its construction was conducted in three stages: (a) a pre-study to generate items (b) a factor analysis on 73 items found and (c) 24 items forming 5 factors were extracted:

- Interaction Engagement

- Respect for Cultural Differences

- Interaction Confidence

- Interaction Enjoymnent

- Interaction Attentiveness items

Fritz, Möllenberg and Chen (2002) [60], conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the Chen and Starosta instrument and confirmed the validity of the overall structure of the instrument, but noticed some minor weaknesses.

A copy of the Intercultural Sensitivity Scale published by Fritz et al. is here

Intercultural effectivenes scale (IES)

Portalla and Chen (2010) [61] “developed and assessed reliability and validity of a new instrument, the Intercultural Effectiveness Scale (IES).” (abstract). “Intercultural communication competence (ICC) can be conceptualized as an individual’s ability to achieve their communication goal while effectively and appropriately utilizing communication behaviors to negotiate between the different identities present within a culturally diverse environment. ICC is comprised of three dimensions, including intercultural awareness, intercultural sensitivity, and intercultural effectiveness (Chen & Starosta, 1996).” (cited by Portall & Chen, 2010:21) [61]

“Based on a review of the literature, 76 items important for intercultural effectiveness were generated. A total of 653 college students rated these items in two separate stages and generated a 20-item final version of the instrument which contains six factors.” (Portalla and Chen: 2010:21)

In a literature review, the authors identified several components that could accound for interculturally effective behaviors: “message skills, interaction management, behavioral flexibility, identity management, and relationship cultivation (Chen,1989, 2005; Martin & Hammer, 1989; Ruben, 1977; Spitzberg & Changnon, 2009).”

The Intercultural Effectivemeness Scale (IES) is here

Causes of culture shock scale

Goldstein and Keller (2015) developed a causes of culture shock scale. [62]

This scale was developed on the basis of culture shock and intercultural adjustment literature as well as study abroad pre-departure resources.

Intercultural development inventory