Inquiry-based learning: Difference between revisions

| (98 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== | ==Definition== | ||

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is | Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is a [[project-oriented learning | project-oriented]] [[pedagogic strategy]] based on [[constructivism|constructivist]] and [[socio-constructivism|socio-constructivist]] theories of learning (Eick & Reed, 2002). | ||

See also: [[Case-based learning]], [[discovery learning]], [[WebQuest]], [[Le Monde De Darwin]], [[Project-based science model]], [[Community of inquiry model]] | |||

{{quotation|Inquiry learning is not about memorizing facts - it is about formulation questions and finding appropriate resolutions to questions and issues. Inquiry can be a complex undertaking and it therefore requires dedicated instructional design and support to facilitate that students experience the excitement of solving a task or problem on their own. Carefully designed inquiry learning environments can assist students in the process of transforming information and data into useful knowledge}} ([http://kaleidoscope.gw.utwente.nl/SIG%2DIL/ Computer Supported Inquiry Learning], retrieved 18:31, 28 June 2007 (MEST). | |||

Inquiry-based learning is often described as a cycle or a spiral, | |||

which implies formulation of a question, investigation, creation of a solution or an appropriate response, discussion and reflexion in connexion with results (Bishop et al., 2004). | |||

IBL is a student-centered and student-lead process. The purpose is to engage the student in active learning, ideally based on their own questions. Learning activities are organized in a cyclic way, independently of the subject. Each question leads to the creation of new ideas and other questions. | |||

With this | This learning process by exploration of the natural or the constructed/social world leads the learner to questions and discoveries in the seeking of new understandings. With this [[pedagogic strategy]], children learn science by doing it (Aubé & David,2003). The main goal is [[conceptual change]]. | ||

IBL is a [[socio-constructivism|socio-constructivist]] design because of [[collaborative learning | collaborative]] work within which the student finds resources, uses tools and resources produced by inquiry partners. Thus, the student make progress by work-sharing, talking and building on everyone's work. | |||

==Models== | |||

There are many models described in the literature. We shall present as an example the ''cyclic inquiry model'' of [http://chipbruce.net/about/ "Chip" Bruce's] [http://chipbruce.net/resources/inquiry-based-learning/defining-inquiry-based-learning/ What is inquiry-based learning?]. The model was originally hosted at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) (and some links below needed fixing ....) | |||

===Cyclic Inquiry model=== | === Cyclic Inquiry model=== | ||

The purpose of | The purpose of the UIUC inquiry model is the creation of new ideas and concepts, and their spreading in the classroom. | ||

Inquiry cycle is | The Inquiry cycle is a process which engages students to ask and answer questions on the basis of collected information and which should lead to the creation of new ideas and concepts. | ||

The activity often finishes by the creation of a document which tries to answer the initial questions. | |||

The cycle of inquiry has 5 global steps: Ask, Investigate, Create, Discuss and Reflect. | The cycle of inquiry has 5 global steps: Ask, Investigate, Create, Discuss and Reflect. We will give an example for each step using the "rainbow" example from Villavicencio (2000) who works on light and colors every year with 4 or 5 years old children. | ||

[[Image:IBL_circle.gif]] | [[Image:IBL_circle.gif]] <br> | ||

<small>from: [[http://inquiry.uiuc.edu The Inquiry Page]]</small> | |||

During the preparation of the activity, | During the preparation of the activity, teachers have to think about how many cycles to do, how to end the activity (at the <i>Ask</i> step): when/how to rephrase questions or answer them and express followup questions. | ||

====Ask==== | ====Ask==== | ||

Ask begins with student's curiosity about the world | <i>Ask</i> begins with student's [[curiosity]] about the world, ideally with their own questions. The teacher can stimulate the curiosity of the student by giving an introduction talk related to concepts that have to be acquired. It's important that student formulate their own questions because they then can explicitly express concepts related to the learning subject. | ||

This step focuses on a problem or a question that students begin to define. These questions are redefined again and again during the cycle. Step's borders are blurred: a step is never completely left when the student begins the next one. | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> The teacher gives some mirrors to the children, so they can play with the sunlight which are passing trough the classroom's windows. With these manipulations, students can then formulate some questions about light and colors. | |||

====Investigate==== | |||

<i>Ask</i> naturally leads to <i>Investigate</i> which should exploit initial curiosity and lead to seek and create information. Students or groups of students collect information, study, collect and exploit resources, experiment, look, interview, draw,... They already can redefine "the question", make it clearer or take another direction. <i>Investigate</i> is a self-motivating process totally owned by the active student. | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> Once questions have been asked, the teacher gives to the children some prisms which allow to bend the light and a Round Light Source (RLS), a big cylindrical lamp with four colored windows through a light ray can pass. Then the children can mix the colors and see the result of their mixed ray light on a screen. They begin to collect information... | |||

====Create==== | |||

Collected information begins to merge. Student start making links. Here, ability to synthesize meaning is the spark which creates new knowledge. Student may generate new thoughts, ideas and theories that are not directly inspired by their own experience. They write them down in some kind of report. | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> Some links are created from collected information and children understand that rainbows have to be created by this kind of phenomenon. | |||

====Discuss==== | |||

At this point, students share their ideas with each other, and ask others about their own experiences and investigations. | |||

Such knowledge-sharing is a community process of construction and they begin to understand the meaning of their investigation. | |||

Comparing notes, discussing conclusions and sharing experiences are some examples of this active process. | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> children often and spontaneously sit around the RLS. They discuss and share their newly acquired knowledge with the purpose to understand the mix of colors. Then, they are invited to share their findings with the rest of the class, while the teacher takes notes on the blackboard. | |||

====Reflect==== | |||

This step consists in taking time to look back. Think again about the initial question, the path taken, and the actual conclusions. | |||

Student look back and maybe take some new decisions: "Has a solution been found ?", "did new questions appear?", "What could they ask now ?",... | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> teacher and students take time to look back at the concepts encountered during the earlier steps of the activity. They try to synthesize and to engage further planning on the basis of their recently acquired concepts. | |||

====Continuation==== | |||

Once the first cycle is over, students are back the <i>Ask</i> step and they can choose between two options: | |||

#Ask: a new cycle starts, fed by the new questions or reformulations of earlier ones. The teacher can create groups to stimulate discussions and interest. | |||

#Answer: the activity is ending. The teacher has to finish it by broadening: The initial questions with their responses, the reformulated ones, new ones that appeared during the activity. Making a synthesis is always a better solution, even if this step is not the purpose of an entire cycle. | |||

<strong>Rainbow Scenario :</strong> the teacher sets students free to repeat their experiments or to try different things. Some students try to replicate what their friends have done, others do the same things with or without variants. A new cycle begins. | |||

The advantage of this model is that it can be applied with lots of student types and lots of matters. Moreover, the teacher can design the scenario by focusing on a part of the cycle or another. He can use one, few or more cycle. | |||

Most often, a single cycle (formal or not) is not enough and because of that, this model is often drawn in a spiral shape. | |||

==== It is just a model ==== | |||

{{quotation|There is usually a strong caution against interpreting steps in the cycle as all being necessary or in a rigid order. In fact, inquiry learning is less well characterized by a series of steps for learning than it is by situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991). This is a phrase describing how learning happens as a function of the activity, context and culture in which it occurs, rather than through abstract and decontextualized presentations. People thus learn through their participation in a community of practice. Learning is a process of moving from the periphery of a community to its center, that is, going from legitimate peripheral participation to full enculturatation. Most of this process is incidental rather than deliberate.}} ([http://chipbruce.net/resources/inquiry-based-learning/defining-inquiry-based-learning/ What is inquiry-based learning?] (12/2014). | |||

=== Practical inquiry model === | |||

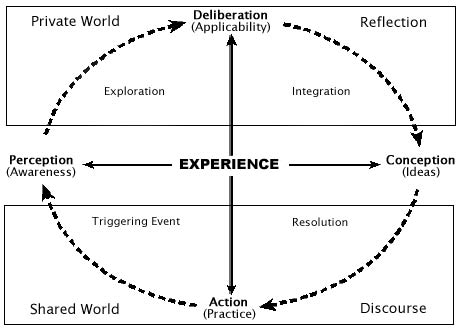

[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096751600000166 Garrison, Anderson & Archer (1999)] presented a model that is based on Dewey's concept of practical inquiry. {{quotation|The reflective phases of practical inquiry or critical thinking presented here are grounded in the pre- and post-reflective phases of the world of practice. The two axes that structure the model are action–deliberation and perception–conception. The first axis is reflection on practice. The second axis is the assimilation of information and the construction of meaning. Together, they constitute the shared and personal worlds. The quadrants reflect the logical or idealized sequence of practical inquiry (i.e., critical thinking) and correspond to the proposed categories of cognitive presence indicators.}} | |||

[[File:Practical-inquiry-model.jpg|none|Practical inquiry model]] | |||

=== Pedaste model === | |||

Pedaste et al. created a five components model based on a systematic review of 32 selected articles on inquiry learning that defined inquiry phases and cycles. The review process firstly resulted in a list of 109 terms for inquiry phases, that were reduced to 34 terms, merged into 11 phases. {{quotation|Orientation, Questioning, Hypothesis Generation, Planning, Observation, Investigation, Analysis, Conclusion, Discussion, Communication, and Reflection. However, it was not practical to retain 11 phases, because inquiry-based learning is often referred as a complex and difficult learning process for the learners (de Jong, van Joolingen, 1998, Veermans et al, 2006)}} (Pedaste et al., 2015). These eleven phases then were organized into groups, also called "general phases": Orientation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Conclusion, and Discussion. Some of these include sub-phases as shown in the table below. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+Pedaste et al., 2015 model of inquiry learning (slightly shortened and altered from the original by DKS) | |||

!General phases | |||

!Processes | |||

!Sub-phases | |||

!Definition of sub-processes | |||

|- | |||

|Orientation | |||

| | |||

* stimulating curiosity about a topic and | |||

* addressing a learning challenge through a problem statement | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="2" |Conceptualization | |||

| rowspan="2" | | |||

* Formulating theory-based questions and /or | |||

* hypotheses. | |||

|Questioning | |||

|generating research questions based on the stated problem. | |||

|- | |||

|''Hypothesis Generation'' | |||

|generating hypotheses regarding the stated problem. | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="3" |Investigation | |||

| rowspan="3" | | |||

* planning exploration or experimentation, | |||

* collecting and analysing data based on the experimental design | |||

* exploration. | |||

|''Exploration'' | |||

|data generation on the basis of a research question. | |||

|- | |||

|''Experimentation'' | |||

|designing and conducting an experiment in order to test a hypothesis. | |||

|- | |||

|''Data Interpretation'' | |||

|making meaning out of collected data and synthesizing new knowledge. | |||

|- | |||

|Conclusion | |||

| | |||

* Drawing conclusions from the data. | |||

* Comparing inferences made based on data with hypotheses or research questions. | |||

| | |||

| | |||

|- | |||

| rowspan="2" |Discussion | |||

| rowspan="2" | | |||

* presenting findings of particular phases to others | |||

* reflective activities. | |||

|''Communication'' | |||

|Presenting outcomes of an inquiry phase or of the whole inquiry cycle to others (peers, teachers) and collecting feedback from them. Discussion with others. | |||

|- | |||

|''Reflection'' | |||

|Describing, critiquing, evaluating and discussing the whole inquiry cycle or a specific phase. Inner discussion. | |||

|} | |||

=== Other models === | |||

The model we presented above represents probably the dominant view of inquiry learning. It combines more radical open-ended socio-constructivist principles ([[Discovery learning]]) with a model of guidance. As opposed to [[Learning by design]], most inquiry-based models do advocate opportunistic (i.e. adaptive) planning by the teacher. Other models include | |||

* [[knowledge-building community model]] (a much more open ended version, geared toward "design mode") | |||

* [[Scaffolded knowledge integration]] | |||

* [[Learning by design]] | |||

* [[Computer simulation]] (The "Dutch school") | |||

== Examples cases == | |||

* [[Le Monde De Darwin]] ([http://darwin.cyberscol.qc.ca Le monde de Darwin]) : Internet educational environment mostly for 8 to 14 years old students. The pedagogy is [[socio-constructivism|socio-constructivist]], with treatment and organization of the information with collaborative work | |||

* Cyber 4OS [http://tecfaetu.unige.ch/wiki/index.php/Cyber4OSCalvin08 Wiki de l'IBL en cours] Lombard, F. (2007). Empowering next generation learners : Wiki supported Inquiry Based Learning ? ([http://www.earli.org/resources/lombard-earli-pbr-inquiry-based-learning_and_wiki-11XI07.pdf Paper]) presented at the European practise based and practitioner conference on learning and instruction Maastricht 14-16 November 2007. | |||

* P. S. Blackawton et al. [[http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2010/12/18/rsbl.2010.1056 Blackawton bees], December 22, 2010, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1056. | |||

** See also: [http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/12/kids-study-bees/ 8-Year-Olds Publish Scientific Bee Study]. | |||

== Tools and software == | |||

* [[Graasp]] | |||

* [[BGuILE]] | |||

* [[WISE]] | |||

* [[Microworld]]s | |||

* Any sort of tool that allows for collaborative writing, e.g. [[groupware]], [[portal]]s, [[wiki]]s. | |||

There are also [[microworld]]s and [[computer simulation]] environments that support inquire learning. A good example is represented by the [http://www.coreflect.org CoReflect]/[http://www.stochasmos.org/ Stochasmos] project and tools. | |||

== Links == | |||

* [http://inquiry.uiuc.edu/ inquiry page] | |||

* [http://kaleidoscope.gw.utwente.nl/SIG%2DIL/ Computer Supported Inquiry Learning] Kaleidoscope and EARLI Special Interest Group (SIG) | |||

== Bibliography == | |||

* Akyol, Zehra; Norm Vaughan , D. Randy Garrison (2011) The impact of course duration on the development of a community of inquiry, ''Interactive Learning Environments'' Vol. 19, Iss. 3, 2011 | |||

* Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). Assessing metacognition in an online community of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(3), 183-190. | |||

* Boomer, Garth (1984). English teaching: Art and science. Address given as a keynote at the annual conference of the National Council for the Teaching of English (NCTE). Detroit. [https://apps.lis.uiuc.edu/wiki/download/attachments/4370295/boomer.webarchive?version=1 Archive files] | |||

* Ackermann, E.K. (2004). Constructing Knowledge and Transforming The World. In Tokoro, M. & Steels, L. (2004). A Learning Zone Of One's Own. pp17-35. IOS Press | |||

* Aubé, M. & David, R. (2003). Le programme d’adoption du monde de Darwin : une exploitation concrète des TIC selon une approche socio-constructiviste. In Taurisson, A. & Senteni, A.(2003). Pédagogie.net : L’essor des communautés d’apprentissage. pp 49-72. | |||

* Aulls, Mark W., & Shore, Bruce M. (2007). Inquiry in education, volume I: The conceptual foundations for research as a curricular imperative. Erlbaum. | |||

* Barab, S.A., Hay, K.E., Barnett, M., & Keating, T. (2000). Virtual Solar System Project: Building understanding through model building. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 719–756. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1098-2736(200009)37:7%3C719::AID-TEA6%3E3.0.CO;2-V/abstract Abstract] | |||

* Benson, Lee, Harkavy, Ira, & Puckett, John (2006). Dewey’s dream: Universities and democracies in an age of education reform. Temple UP. Combines intellectual history of pragmatism, with a special emphasis on Dewey in Chicago, and practical ideas about how universities can engage with communities today | |||

* Berdan, Kristina, et al. (eds.) (2006). Writing for a change: Boosting literacy and learning through social action. Jossey-Bass. How to promote community-based writing. | |||

* Bishop, A.P.,Bertram, B.C.,Lunsford, K.J. & al. (2004). Supporting Community Inquiry with Digital Resources. Journal Of Digital Information, 5 (3). | |||

* Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University (1998). [http://naples.cc.sunysb.edu/Pres/boyer.nsf/ Reinventing undergraduate education: A Blueprint for America’s Research Universities.] | |||

* Bridges, Katie, McPhee, Marian, & Appenzeller, Tom. Comparative study of structured and inquiry learning. Three middle school teachers describe their and their students experiences with different teaching styles. | |||

* Bruce, B. C. (Ed.) (2003). [http://chipbruce.wordpress.com/2003/04/01/literacy-in-the-information-age/ Literacy in the information age: Inquiries into meaning making with new technologies]. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. | |||

* Bruner, J. S. (1965/1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. | |||

* Chakroun, M. (2003). Conception et mise en place d'un module pédagogique pour portails communautaires Postnuke. Insat, Tunis. Mémoire de licence non publié. | |||

* De Jong, T. & Van Joolingen, W.R. (1997). Scientific Discovery Learning with Computer Simulations of Conceptual Domains. University of Twente, The Netherland | |||

* De Jong, T. (2006b). Scaffolds for computer simulation based scientific discovery learning. In J. Elen & R. E. Clark (Eds.), Dealing with complexity in learning environments (pp. 107-128). London: Elsevier Science Publishers. | |||

* De Jong, Ton (2006) Computer Simulations: Technological Advances in Inquiry Learning, Science 28 April 2006 312: 532-533 [http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1127750 DOI: 10.1126/science.1127750] | |||

* Dewey, J. (1938) ''Logic: The Theory of Inquiry'', New York: Holt. | |||

* Dewey, John (1933). How we think: A rethinking of the relation of reflective thinking in the educative process. New York: D. C. Heath. | |||

* Drie, J. van, Boxtel, C. van, & Kanselaar, G. (2003). Supporting historical reasoning in CSCL. In: B. Wasson, S. Ludvigsen, & U. Hoppe (Eds.). Designing for Change in Networked Learning Environments. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Press, pp. 93-103. ISBN 1-4020-1383-3. | |||

* Duckworth, E. (1986). Inventing Density. Monography by the North Dakota Study Group on Evaluation, Grand Forks, ND, 1986. http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inventingdensity.html | |||

* Eick, C.J. & Reed, C.J. (2002). What Makes an Inquiry Oriented Science Teacher? The Influence of Learning Histories on Student Teacher Role Identity and Practice. Science Teacher Education, 86, pp 401-416. | |||

* Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Ufer, S., Sodian, B., Hussmann, H., Pekrun, R., ... & Eberle, J. (2014). Scientific Reasoning and Argumentation: Advancing an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda in Education. Frontline Learning Research, 2(3), 28-45. | |||

* Furtak, E. M., Seidel, T., Iverson, H., & Briggs, D. C. (2012). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Studies of Inquiry-Based Science Teaching A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 300-329. | |||

* Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72. Retrieved October 28, 2011, from http://sloanconsortium.org/system/files/v11n1_8garrison.pdf | |||

* Gurtner, J-L. (1996). L'apport de Piaget aux études pédagogiques et didactiques. Actes du colloque international Jean Piaget, avril 1996, sous la direction de Ahmed Chabchoub. Publications de l'institut Supérieur de l'Education et de la Formation Continue. | |||

* Hakkarainen, K and Matti Sintonen (2002). The Interrogative Model of Inquiry and Computer- Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 11 (1), 25-43. (NOTE: we should cite from this one !) | |||

* Hakkarainen, K, (2003). Emergence of Progressive-Inquiry Culture in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 6 (2), 199-220. | |||

* Hawkins, David (1965). Messing about in science. Science and Children, 2(5), 5-9. Reprinted (1974) in The informed vision: Essays on learning and human nature (pp. 63-75). New York: Agathon. | |||

* Hubbard, Ruth S., & Power, B. M. (1993). The art of classroom inquiry: A handbook for teacher-researchers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. | |||

* Jeffs, Tony, & Smith, Mark (eds.)(1990). Using informal education. Open University Press. | |||

* Joolingen van, Dr. W.R. and King, S. and Jong de, Prof. dr. T. (1997) The SimQuest authoring system for simulation-based discovery learning. In: B. du Boulay & R. Mizoguchi (Eds.), Artificial intelligence and education: Knowledge and media in learning systems. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp. 79-86. [http://doc.utwente.nl/27531/1/K27531__.PDF PDF] | |||

* Kasl, E & Yorks, L. (2002). Collaborative Inquiry for Adult Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 94, summer 2002. | |||

* Keys, C.W. & Bryan, L.A. (2001). Co-Constructing Inquiry-Based Science with Teachers : Essential Research for Lasting Reform. Journal Of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (6), pp 631-645. | |||

* Khan, P., & O’Rourke, K. (2005). [http://www.aishe.org/readings/2005-2/contents.html Understanding enquiry-based learning]. In Barrett, T., MacLabhrainn, I., Fallon, H. (eds), Handbook of enquiry and problem based learning. Galway: CELT. | |||

* Koschmann, T. (Ed.)(1996). CSCL: Theory and practice of an emerging paradigm. Erlbaum. | |||

Lattion, S.(2005). Développement et implémentation d'un module d'apprentissage par investigation (inquiry-based learning) au sein d'une plateforme de type PostNuke. Genève, Suisse. Mémoire de diplôme non-publié | * Lattion, S.(2005). Développement et implémentation d'un module d'apprentissage par investigation (inquiry-based learning) au sein d'une plateforme de type PostNuke. Genève, Suisse. Mémoire de diplôme non-publié. [http://tecfa.unige.ch/staf/staf-i/lattion/staf25/memoire.pdf PDF] | ||

* Linn, Marcia C. Elizabeth A. Davis & Philip Bell (2004). (Eds.), Internet Environments for Science Education: how information technologies can support the learning of science, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0-8058-4303-5 | |||

* Mayer, R. E. (2004), Should there be a three strikes rule against pure discovery? The case for guided methods of instruction. Am. Psych. 59 (14). | |||

* Minner, D. D., Levy, A. J. and Century, J. (2010), Inquiry-based science instruction—what is it and does it matter? Results from a research synthesis years 1984 to 2002. J. Res. Sci. Teach., 47: 474–496. [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tea.20347/pdf doi: 10.1002/tea.20347] | |||

* McKenzie, J. (1999). Scaffolding for Success. From Now On, ,The Educationnal Technology Journal, 9(4). | |||

* National Science Foundation, in Foundations: Inquiry: Thoughts, Views, and Strategies for the K-5 Classroom (NSF, Arlington, VA, 2000), vol. 2, pp. 1-5 [http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2000/nsf99148/intro.htm HTML]. | |||

* Nespor, J.(1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19, pp 317-328. | |||

* Noddings, N. (2005). [http://www.infed.org/biblio/noddings_caring_in_education.htm Caring in education]. The encyclopedia of informal education. | |||

* Noddings, Nel (1984). Caring, a feminine approach to ethics & moral education. Berkeley: University of California Press. | |||

* Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., De Jong, T., Van Riesen, S. A., Kamp, E. T., ... & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational research review, 14, 47-61. | |||

* Polman, Joseph (2000), Designing Project-based science, Teachers College Press, New York. | |||

* Regenspan, Barbara (2002). Parallel practices. Social justice-focused teacher education and the elementary school classroom. New York: P. Lang. Chapters 1 & 5. | |||

* Vermont Elementary Science Project. (1995). Inquiry Based Science: What Does It Look Like? Connect Magazine, March-April 1995, p. 13. published by Synergy Learning. http://http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inquiry_based.html | |||

* Villavicencio, J. (2000). Inquiry in Kindergarten. Connect Magazine, 13 (4), March/April 2000. Synergy Learning Publication. | |||

* Vosniadou, S., Ioannides, C., Dimitrakopoulou, A. & Papademetriou, E. (2001). Designing learning environments to promote conceptual change in science. Learning and Instruction ,11, pp 381-419. | |||

* Waight Noemi, Fouad Abd-El-Khalick, From scientific practice to high school science classrooms: Transfer of scientific technologies and realizations of authentic inquiry, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2011, 48, 1. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tea.20393 DOI:10.1002/tea.20393] | |||

* Watson, B. & Kopnicek, R. (1990). Teaching for Conceptual Change : confronting Children Experience. Phi Delta Kappan, May 1990, pp 680-684. | |||

[[fr:apprentissage par investigation]] | |||

[[Category:Pedagogic strategies]] | |||

[[Category:Instructional theories]] | |||

[[Category:Project-oriented instructional design models]] | |||

[[Category:Instructional design models]] | |||

[[Category: Collaborative learning]] | |||

[[Category:Community-oriented instructional design models]] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:45, 14 May 2019

Definition

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is a project-oriented pedagogic strategy based on constructivist and socio-constructivist theories of learning (Eick & Reed, 2002).

See also: Case-based learning, discovery learning, WebQuest, Le Monde De Darwin, Project-based science model, Community of inquiry model

“Inquiry learning is not about memorizing facts - it is about formulation questions and finding appropriate resolutions to questions and issues. Inquiry can be a complex undertaking and it therefore requires dedicated instructional design and support to facilitate that students experience the excitement of solving a task or problem on their own. Carefully designed inquiry learning environments can assist students in the process of transforming information and data into useful knowledge” (Computer Supported Inquiry Learning, retrieved 18:31, 28 June 2007 (MEST).

Inquiry-based learning is often described as a cycle or a spiral, which implies formulation of a question, investigation, creation of a solution or an appropriate response, discussion and reflexion in connexion with results (Bishop et al., 2004). IBL is a student-centered and student-lead process. The purpose is to engage the student in active learning, ideally based on their own questions. Learning activities are organized in a cyclic way, independently of the subject. Each question leads to the creation of new ideas and other questions.

This learning process by exploration of the natural or the constructed/social world leads the learner to questions and discoveries in the seeking of new understandings. With this pedagogic strategy, children learn science by doing it (Aubé & David,2003). The main goal is conceptual change.

IBL is a socio-constructivist design because of collaborative work within which the student finds resources, uses tools and resources produced by inquiry partners. Thus, the student make progress by work-sharing, talking and building on everyone's work.

Models

There are many models described in the literature. We shall present as an example the cyclic inquiry model of "Chip" Bruce's What is inquiry-based learning?. The model was originally hosted at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) (and some links below needed fixing ....)

Cyclic Inquiry model

The purpose of the UIUC inquiry model is the creation of new ideas and concepts, and their spreading in the classroom.

The Inquiry cycle is a process which engages students to ask and answer questions on the basis of collected information and which should lead to the creation of new ideas and concepts. The activity often finishes by the creation of a document which tries to answer the initial questions.

The cycle of inquiry has 5 global steps: Ask, Investigate, Create, Discuss and Reflect. We will give an example for each step using the "rainbow" example from Villavicencio (2000) who works on light and colors every year with 4 or 5 years old children.

from: [The Inquiry Page]

During the preparation of the activity, teachers have to think about how many cycles to do, how to end the activity (at the Ask step): when/how to rephrase questions or answer them and express followup questions.

Ask

Ask begins with student's curiosity about the world, ideally with their own questions. The teacher can stimulate the curiosity of the student by giving an introduction talk related to concepts that have to be acquired. It's important that student formulate their own questions because they then can explicitly express concepts related to the learning subject.

This step focuses on a problem or a question that students begin to define. These questions are redefined again and again during the cycle. Step's borders are blurred: a step is never completely left when the student begins the next one.

Rainbow Scenario : The teacher gives some mirrors to the children, so they can play with the sunlight which are passing trough the classroom's windows. With these manipulations, students can then formulate some questions about light and colors.

Investigate

Ask naturally leads to Investigate which should exploit initial curiosity and lead to seek and create information. Students or groups of students collect information, study, collect and exploit resources, experiment, look, interview, draw,... They already can redefine "the question", make it clearer or take another direction. Investigate is a self-motivating process totally owned by the active student.

Rainbow Scenario : Once questions have been asked, the teacher gives to the children some prisms which allow to bend the light and a Round Light Source (RLS), a big cylindrical lamp with four colored windows through a light ray can pass. Then the children can mix the colors and see the result of their mixed ray light on a screen. They begin to collect information...

Create

Collected information begins to merge. Student start making links. Here, ability to synthesize meaning is the spark which creates new knowledge. Student may generate new thoughts, ideas and theories that are not directly inspired by their own experience. They write them down in some kind of report.

Rainbow Scenario : Some links are created from collected information and children understand that rainbows have to be created by this kind of phenomenon.

Discuss

At this point, students share their ideas with each other, and ask others about their own experiences and investigations. Such knowledge-sharing is a community process of construction and they begin to understand the meaning of their investigation. Comparing notes, discussing conclusions and sharing experiences are some examples of this active process.

Rainbow Scenario : children often and spontaneously sit around the RLS. They discuss and share their newly acquired knowledge with the purpose to understand the mix of colors. Then, they are invited to share their findings with the rest of the class, while the teacher takes notes on the blackboard.

Reflect

This step consists in taking time to look back. Think again about the initial question, the path taken, and the actual conclusions. Student look back and maybe take some new decisions: "Has a solution been found ?", "did new questions appear?", "What could they ask now ?",...

Rainbow Scenario : teacher and students take time to look back at the concepts encountered during the earlier steps of the activity. They try to synthesize and to engage further planning on the basis of their recently acquired concepts.

Continuation

Once the first cycle is over, students are back the Ask step and they can choose between two options:

- Ask: a new cycle starts, fed by the new questions or reformulations of earlier ones. The teacher can create groups to stimulate discussions and interest.

- Answer: the activity is ending. The teacher has to finish it by broadening: The initial questions with their responses, the reformulated ones, new ones that appeared during the activity. Making a synthesis is always a better solution, even if this step is not the purpose of an entire cycle.

Rainbow Scenario : the teacher sets students free to repeat their experiments or to try different things. Some students try to replicate what their friends have done, others do the same things with or without variants. A new cycle begins.

The advantage of this model is that it can be applied with lots of student types and lots of matters. Moreover, the teacher can design the scenario by focusing on a part of the cycle or another. He can use one, few or more cycle. Most often, a single cycle (formal or not) is not enough and because of that, this model is often drawn in a spiral shape.

It is just a model

“There is usually a strong caution against interpreting steps in the cycle as all being necessary or in a rigid order. In fact, inquiry learning is less well characterized by a series of steps for learning than it is by situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991). This is a phrase describing how learning happens as a function of the activity, context and culture in which it occurs, rather than through abstract and decontextualized presentations. People thus learn through their participation in a community of practice. Learning is a process of moving from the periphery of a community to its center, that is, going from legitimate peripheral participation to full enculturatation. Most of this process is incidental rather than deliberate.” (What is inquiry-based learning? (12/2014).

Practical inquiry model

Garrison, Anderson & Archer (1999) presented a model that is based on Dewey's concept of practical inquiry. “The reflective phases of practical inquiry or critical thinking presented here are grounded in the pre- and post-reflective phases of the world of practice. The two axes that structure the model are action–deliberation and perception–conception. The first axis is reflection on practice. The second axis is the assimilation of information and the construction of meaning. Together, they constitute the shared and personal worlds. The quadrants reflect the logical or idealized sequence of practical inquiry (i.e., critical thinking) and correspond to the proposed categories of cognitive presence indicators.”

Pedaste model

Pedaste et al. created a five components model based on a systematic review of 32 selected articles on inquiry learning that defined inquiry phases and cycles. The review process firstly resulted in a list of 109 terms for inquiry phases, that were reduced to 34 terms, merged into 11 phases. “Orientation, Questioning, Hypothesis Generation, Planning, Observation, Investigation, Analysis, Conclusion, Discussion, Communication, and Reflection. However, it was not practical to retain 11 phases, because inquiry-based learning is often referred as a complex and difficult learning process for the learners (de Jong, van Joolingen, 1998, Veermans et al, 2006)” (Pedaste et al., 2015). These eleven phases then were organized into groups, also called "general phases": Orientation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Conclusion, and Discussion. Some of these include sub-phases as shown in the table below.

| General phases | Processes | Sub-phases | Definition of sub-processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orientation |

|

||

| Conceptualization |

|

Questioning | generating research questions based on the stated problem. |

| Hypothesis Generation | generating hypotheses regarding the stated problem. | ||

| Investigation |

|

Exploration | data generation on the basis of a research question. |

| Experimentation | designing and conducting an experiment in order to test a hypothesis. | ||

| Data Interpretation | making meaning out of collected data and synthesizing new knowledge. | ||

| Conclusion |

|

||

| Discussion |

|

Communication | Presenting outcomes of an inquiry phase or of the whole inquiry cycle to others (peers, teachers) and collecting feedback from them. Discussion with others. |

| Reflection | Describing, critiquing, evaluating and discussing the whole inquiry cycle or a specific phase. Inner discussion. |

Other models

The model we presented above represents probably the dominant view of inquiry learning. It combines more radical open-ended socio-constructivist principles (Discovery learning) with a model of guidance. As opposed to Learning by design, most inquiry-based models do advocate opportunistic (i.e. adaptive) planning by the teacher. Other models include

- knowledge-building community model (a much more open ended version, geared toward "design mode")

- Scaffolded knowledge integration

- Learning by design

- Computer simulation (The "Dutch school")

Examples cases

- Le Monde De Darwin (Le monde de Darwin) : Internet educational environment mostly for 8 to 14 years old students. The pedagogy is socio-constructivist, with treatment and organization of the information with collaborative work

- Cyber 4OS Wiki de l'IBL en cours Lombard, F. (2007). Empowering next generation learners : Wiki supported Inquiry Based Learning ? (Paper) presented at the European practise based and practitioner conference on learning and instruction Maastricht 14-16 November 2007.

- P. S. Blackawton et al. [Blackawton bees, December 22, 2010, doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1056.

- See also: 8-Year-Olds Publish Scientific Bee Study.

Tools and software

- Graasp

- BGuILE

- WISE

- Microworlds

- Any sort of tool that allows for collaborative writing, e.g. groupware, portals, wikis.

There are also microworlds and computer simulation environments that support inquire learning. A good example is represented by the CoReflect/Stochasmos project and tools.

Links

- inquiry page

- Computer Supported Inquiry Learning Kaleidoscope and EARLI Special Interest Group (SIG)

Bibliography

- Akyol, Zehra; Norm Vaughan , D. Randy Garrison (2011) The impact of course duration on the development of a community of inquiry, Interactive Learning Environments Vol. 19, Iss. 3, 2011

- Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). Assessing metacognition in an online community of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(3), 183-190.

- Boomer, Garth (1984). English teaching: Art and science. Address given as a keynote at the annual conference of the National Council for the Teaching of English (NCTE). Detroit. Archive files

- Ackermann, E.K. (2004). Constructing Knowledge and Transforming The World. In Tokoro, M. & Steels, L. (2004). A Learning Zone Of One's Own. pp17-35. IOS Press

- Aubé, M. & David, R. (2003). Le programme d’adoption du monde de Darwin : une exploitation concrète des TIC selon une approche socio-constructiviste. In Taurisson, A. & Senteni, A.(2003). Pédagogie.net : L’essor des communautés d’apprentissage. pp 49-72.

- Aulls, Mark W., & Shore, Bruce M. (2007). Inquiry in education, volume I: The conceptual foundations for research as a curricular imperative. Erlbaum.

- Barab, S.A., Hay, K.E., Barnett, M., & Keating, T. (2000). Virtual Solar System Project: Building understanding through model building. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 719–756. Abstract

- Benson, Lee, Harkavy, Ira, & Puckett, John (2006). Dewey’s dream: Universities and democracies in an age of education reform. Temple UP. Combines intellectual history of pragmatism, with a special emphasis on Dewey in Chicago, and practical ideas about how universities can engage with communities today

- Berdan, Kristina, et al. (eds.) (2006). Writing for a change: Boosting literacy and learning through social action. Jossey-Bass. How to promote community-based writing.

- Bishop, A.P.,Bertram, B.C.,Lunsford, K.J. & al. (2004). Supporting Community Inquiry with Digital Resources. Journal Of Digital Information, 5 (3).

- Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University (1998). Reinventing undergraduate education: A Blueprint for America’s Research Universities.

- Bridges, Katie, McPhee, Marian, & Appenzeller, Tom. Comparative study of structured and inquiry learning. Three middle school teachers describe their and their students experiences with different teaching styles.

- Bruce, B. C. (Ed.) (2003). Literacy in the information age: Inquiries into meaning making with new technologies. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

- Bruner, J. S. (1965/1960). The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Chakroun, M. (2003). Conception et mise en place d'un module pédagogique pour portails communautaires Postnuke. Insat, Tunis. Mémoire de licence non publié.

- De Jong, T. & Van Joolingen, W.R. (1997). Scientific Discovery Learning with Computer Simulations of Conceptual Domains. University of Twente, The Netherland

- De Jong, T. (2006b). Scaffolds for computer simulation based scientific discovery learning. In J. Elen & R. E. Clark (Eds.), Dealing with complexity in learning environments (pp. 107-128). London: Elsevier Science Publishers.

- De Jong, Ton (2006) Computer Simulations: Technological Advances in Inquiry Learning, Science 28 April 2006 312: 532-533 DOI: 10.1126/science.1127750

- Dewey, J. (1938) Logic: The Theory of Inquiry, New York: Holt.

- Dewey, John (1933). How we think: A rethinking of the relation of reflective thinking in the educative process. New York: D. C. Heath.

- Drie, J. van, Boxtel, C. van, & Kanselaar, G. (2003). Supporting historical reasoning in CSCL. In: B. Wasson, S. Ludvigsen, & U. Hoppe (Eds.). Designing for Change in Networked Learning Environments. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Press, pp. 93-103. ISBN 1-4020-1383-3.

- Duckworth, E. (1986). Inventing Density. Monography by the North Dakota Study Group on Evaluation, Grand Forks, ND, 1986. http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inventingdensity.html

- Eick, C.J. & Reed, C.J. (2002). What Makes an Inquiry Oriented Science Teacher? The Influence of Learning Histories on Student Teacher Role Identity and Practice. Science Teacher Education, 86, pp 401-416.

- Fischer, F., Kollar, I., Ufer, S., Sodian, B., Hussmann, H., Pekrun, R., ... & Eberle, J. (2014). Scientific Reasoning and Argumentation: Advancing an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda in Education. Frontline Learning Research, 2(3), 28-45.

- Furtak, E. M., Seidel, T., Iverson, H., & Briggs, D. C. (2012). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Studies of Inquiry-Based Science Teaching A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 300-329.

- Garrison, D. R. (2007). Online community of inquiry review: Social, cognitive, and teaching presence issues. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 11(1), 61-72. Retrieved October 28, 2011, from http://sloanconsortium.org/system/files/v11n1_8garrison.pdf

- Gurtner, J-L. (1996). L'apport de Piaget aux études pédagogiques et didactiques. Actes du colloque international Jean Piaget, avril 1996, sous la direction de Ahmed Chabchoub. Publications de l'institut Supérieur de l'Education et de la Formation Continue.

- Hakkarainen, K and Matti Sintonen (2002). The Interrogative Model of Inquiry and Computer- Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 11 (1), 25-43. (NOTE: we should cite from this one !)

- Hakkarainen, K, (2003). Emergence of Progressive-Inquiry Culture in Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, Science and Education, 6 (2), 199-220.

- Hawkins, David (1965). Messing about in science. Science and Children, 2(5), 5-9. Reprinted (1974) in The informed vision: Essays on learning and human nature (pp. 63-75). New York: Agathon.

- Hubbard, Ruth S., & Power, B. M. (1993). The art of classroom inquiry: A handbook for teacher-researchers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Jeffs, Tony, & Smith, Mark (eds.)(1990). Using informal education. Open University Press.

- Joolingen van, Dr. W.R. and King, S. and Jong de, Prof. dr. T. (1997) The SimQuest authoring system for simulation-based discovery learning. In: B. du Boulay & R. Mizoguchi (Eds.), Artificial intelligence and education: Knowledge and media in learning systems. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp. 79-86. PDF

- Kasl, E & Yorks, L. (2002). Collaborative Inquiry for Adult Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 94, summer 2002.

- Keys, C.W. & Bryan, L.A. (2001). Co-Constructing Inquiry-Based Science with Teachers : Essential Research for Lasting Reform. Journal Of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (6), pp 631-645.

- Khan, P., & O’Rourke, K. (2005). Understanding enquiry-based learning. In Barrett, T., MacLabhrainn, I., Fallon, H. (eds), Handbook of enquiry and problem based learning. Galway: CELT.

- Koschmann, T. (Ed.)(1996). CSCL: Theory and practice of an emerging paradigm. Erlbaum.

- Lattion, S.(2005). Développement et implémentation d'un module d'apprentissage par investigation (inquiry-based learning) au sein d'une plateforme de type PostNuke. Genève, Suisse. Mémoire de diplôme non-publié. PDF

- Linn, Marcia C. Elizabeth A. Davis & Philip Bell (2004). (Eds.), Internet Environments for Science Education: how information technologies can support the learning of science, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0-8058-4303-5

- Mayer, R. E. (2004), Should there be a three strikes rule against pure discovery? The case for guided methods of instruction. Am. Psych. 59 (14).

- Minner, D. D., Levy, A. J. and Century, J. (2010), Inquiry-based science instruction—what is it and does it matter? Results from a research synthesis years 1984 to 2002. J. Res. Sci. Teach., 47: 474–496. doi: 10.1002/tea.20347

- McKenzie, J. (1999). Scaffolding for Success. From Now On, ,The Educationnal Technology Journal, 9(4).

- National Science Foundation, in Foundations: Inquiry: Thoughts, Views, and Strategies for the K-5 Classroom (NSF, Arlington, VA, 2000), vol. 2, pp. 1-5 HTML.

- Nespor, J.(1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19, pp 317-328.

- Noddings, N. (2005). Caring in education. The encyclopedia of informal education.

- Noddings, Nel (1984). Caring, a feminine approach to ethics & moral education. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., De Jong, T., Van Riesen, S. A., Kamp, E. T., ... & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational research review, 14, 47-61.

- Polman, Joseph (2000), Designing Project-based science, Teachers College Press, New York.

- Regenspan, Barbara (2002). Parallel practices. Social justice-focused teacher education and the elementary school classroom. New York: P. Lang. Chapters 1 & 5.

- Vermont Elementary Science Project. (1995). Inquiry Based Science: What Does It Look Like? Connect Magazine, March-April 1995, p. 13. published by Synergy Learning. http://http://www.exploratorium.edu/IFI/resources/classroom/inquiry_based.html

- Villavicencio, J. (2000). Inquiry in Kindergarten. Connect Magazine, 13 (4), March/April 2000. Synergy Learning Publication.

- Vosniadou, S., Ioannides, C., Dimitrakopoulou, A. & Papademetriou, E. (2001). Designing learning environments to promote conceptual change in science. Learning and Instruction ,11, pp 381-419.

- Waight Noemi, Fouad Abd-El-Khalick, From scientific practice to high school science classrooms: Transfer of scientific technologies and realizations of authentic inquiry, Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 2011, 48, 1. DOI:10.1002/tea.20393

- Watson, B. & Kopnicek, R. (1990). Teaching for Conceptual Change : confronting Children Experience. Phi Delta Kappan, May 1990, pp 680-684.