Technology acceptance model

Based on the theory of reasoned Action, Davis ( 1986 ) developed the Technology Acceptance Model which deals more specifically with the prediction of the acceptability of an information system. The purpose of this model is to predict the acceptability of a tool and to identify the modifications which must be brought to the system in order to make it acceptable to users. This model suggests that the acceptability of an information system is determined by two main factors: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use.

Perceived usefulness is defined as being the degree to which a person believes that the use of a system will improve his performance. Perceived ease of use refers to the degree to which a person believes that the use of a system will be effortless. Several factorial analyses demonstrated that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use can be considered as two different dimensions (Hauser et Shugan, 1980 ; Larcker et Lessig, 1980 ; Swanson, 1987).

As demonstrated in the theory of reasoned Action, the Technology Acceptance Model postulates that the use of an information system is determined by the behavioral intention, but on the other hand, that the behavioral intention is determined by the person’s attitude towards the use of the system and also by his perception of its utility. According to Davis, the attitude of an individual is not the only factor that determines his use of a system, but is also based on the impact which it may have on his performance. Therefore, even if an employee does not welcome an information system, the probability that he will use it is high if he perceives that the system will improve his performance at work. Besides, the Technology Acceptance Model hypothesizes a direct link between perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. With two systems offering the same features, a user will find more useful the one that he finds easier to use (Dillon and Morris, on 1996).

Technology Acceptance Model from Davis, Bagozzi et Warshaw (1989)

According to Davis ( 1986 ) perceived ease of use also influences in a significant way the attitude of an individual through two main mechanisms: self-efficacy and instrumentality. Self-efficacy is a concept developed by Bandura ( 1982 ) which explains that the more a system is easy to use, the greater should be the user’s sense of efficacy. Moreover, a tool that is easy to use will make the user feel that he has a control over what he is doing (Lepper on 1985). Efficacy is one of the main factors underlying intrinsic motivation (Bandura on 1982; Lepper on 1985) and it is what illustrates here the direct link between perceived ease of use and attitude. Perceived ease of use can also contribute in an instrumental way in improving a person’s performance. Due to the fact that the user will have to deploy less efforts with a tool that is easy to use, he will be able to spare efforts to accomplish other tasks.(Davis, on 1986).

It is however interesting to note that the research presented by Davis (1989) to validate his model, demonstrates that the link between the intention to use an information system and perceived usefulness is stronger than perceived ease of use. According to this model, we can therefore expect that the factor which influences the most a user is the perceived usefulness of a tool.

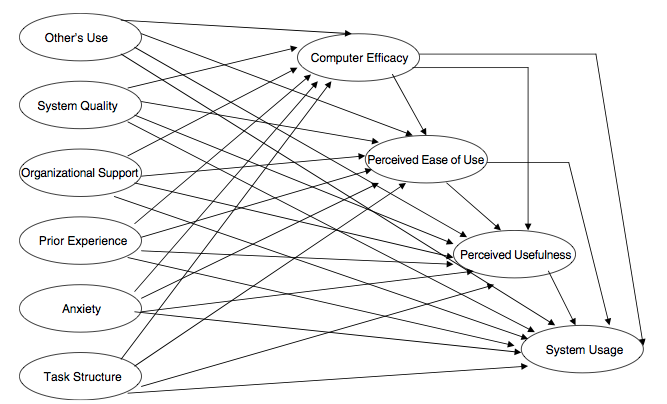

Although the intial TAM model was empirically validated, it explained only a fraction of the variance of the outcome variable, IT usage (from 4% to 45%, according to McFarland and Hamilton, 2006). Therefore, many authors have refined the initial model, trying to find the latent factors underlying perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. in TAM2, Venkatesh & Davis (2000) showed that social influence processes (subjective norm, voluntarity, image) and cognitive instrumental processes (job relevance, output quality, result demontrability) affected perceived usefulness and intention to use. A notable refinment of the TAM model is proposed by (Mc Farland and Hamilton, 2006). Their model assumes that 6 contextual variables (prior experience, other's use, computer anxiety, system quality, task structure, and organizational support) affect the dependant variable system usage through 3 mediating variables (computer efficacy, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness). The model also postulates direct relations between the external variables and system usage (see Figure 2)and not only mediation through perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness.

Figure 2. Adding contextual specificity to the Technology Acceptance Model from McFarland & Hamilton (2006)

The results comforted the research model, showing that "system usage was directly and significantly affected by task structure, prior experience, other's use, organizational support, anxiety, and system quality." Mediation effect were also shown as predicted. Thus However, for some relations, the effect went in the opposite direction from expected, like other's use lowering computer efficacy or high quality systems linked to low frequency of use.

In sum, the initial model or its extension does not completely accounts for the observed variance in system usage. However, the models all agree that computer efficacy affects perceived ease of use, which in turns is strongly related to perceived usefulness.

A meta-analysis conducted by Scherer, Siddiq & Tondeur (2019) showed that TAM models remains a good choice for explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education.

See also

Theory of reasoned action, Theory of Planned Behaviour, Usability and user experience surveys

References

BANDURA A. (1982), Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency, American Psychologist 37 (2) 122-147.

DAVIS, F.; BAGOZZI, R.; and WARSHAW, R. (1989). User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science, Volume 35, 1989, pp. 982-1003.

DILLON, A., & MORRIS, M. G. (1996). User acceptance of information technology: Theories and models. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 31, 3-32.

HAUSER, J. R. and SHUGAN S.M. (1980), "Intensity Measures of Consumer Preference," Operation Research, Vol. 28, No. 2, (March-April), 278-320.

Legris, Paul, John Ingham, Pierre Collerette, Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model, Information & Management, Volume 40, Issue 3, January 2003, Pages 191-204, ISSN 0378-7206, 10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00143-4. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378720601001434)

Ingham, John; Pierre Collerette, Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model, Information & Management, Volume 40, Issue 3, January 2003, Pages 191-204, ISSN 0378-7206, 10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00143-4. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378720601001434)

LARCKER, D.F., and LESSIG, V.P. (1980) Perceived Usefulness of Information: A Psychometric Examination, Decision Sciences, 11 (1).

LEPPER, M. R. (1982, August). Microcomputers in education: Motivational and social issues. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

McFARLAND, D., & HAMILTON, D. (2006). Adding contextual specificity to the technology acceptance model. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(3), 427-447.

Louise K. Schaper, Graham P. Pervan, ICT and OTs: A model of information and communication technology acceptance and utilisation by occupational therapists, International Journal of Medical Informatics, Volume 76, Supplement 1, June 2007, Pages S212-S221, ISSN 1386-5056, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.028. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S138650560600150X)

Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers’ adoption of digital technology in education. Computers & Education, 128, 13–35. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2018.09.009

SWANSON, E. B. (1982). Measuring ....

Venkatesh,V., Morris, M.G., Davis, G.B. & Davis, F.D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540