CSS tutorial

This article or section is currently under construction

In principle, someone is working on it and there should be a better version in a not so distant future.

If you want to modify this page, please discuss it with the person working on it (see the "history")

<pageby nominor="false" comments="false"/>

Introduction

- Learning goals

- Understand the structure of cascading stylesheet (CSS) rules

- Learn how to include CSS in HTML files and/or how to associate a CSS file with HTML

- Learn how to style text elements

- Prerequisites

- Basic HTML, e.g. the HTML and XHTML elements and attributes tutorial

- Moving on

- Level and target population

- Beginners

- Remarks

- THIS WORK IN PROGRESS. I just imported some "text" from teaching slides and now will have to work ... - Daniel K. Schneider 18:56, 7 September 2009 (UTC).

The executive summary

A CSS Style sheet is set of rules that describe how to render (X)HTML or XML elements.

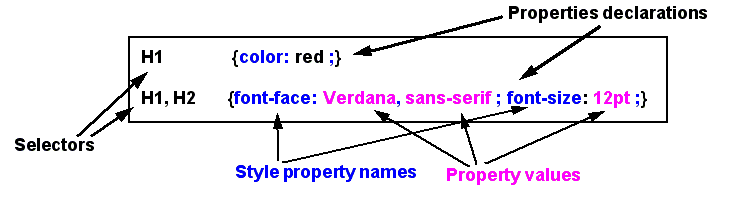

Each rule has two parts:

- The selector: defines to which elements a rule applies

- The declaration: defines rendering, i.e. defines values for style properties

Here is a simple example with two CSS rules for HTML:

P { font-face: Verdana, sans-serif; font-size: 12pt; }

H1, H2, H3 { color: green; }

As we shall see later, the first rule defines that <P> should use a 12pt Verdana font (or a default sans-serif, if not available). The second rules states that all H1, H2 and H3 titles should be green.

Usually CSS rules are defined in a separate file which then is associated with the HTML file. This way one can reuse one stylesheet for many different HTML pages.

See also CSS for XML tutorial

Cascading Style Sheets principles

Purpose of CSS and status of CSS 2 implementation

- Rendering of HTML and (text-centric) XML contents

- Support for Dynamic HTML, dynamic SVG etc. (in particular: appear/disappear, move, etc.)

Advantages

- Separation of content and style: makes web sites easier to maintain

- Multiple rendering: adaptation to media and people (screen size, font size, print, etc.)

- The modern way to define HTML styles (including positioning of elements in the page

- An easy way to render contents of text-centric XML

Disadvantages

- lack of text-transformation in CSS1/CSS2 makes CSS rather unsuitable for data-centric XML or long HTML "articles" (e.g. you can't automatically create a table of contents).

- Implementation of CSS 2 was bad in IE 6 / 7, i.e. there were several bugs and in addition some selectors and properties were not implemented. E.g. the content property was missing. It is needed to display attribute values and/or to add extra text to output. CSS 2 support is fine in IE8, CSS 2.1 is not yet fully implemented.

Implementation

- CSS 1 (1996): Ok in Firefox 1.x /Opera, more or less ok in IE 6

- CSS 2 (1998, revised 2008): More or less ok in Firefox 2.x/Opera, good in Firefox 3.x, not too good in IE 6/7, good in IE8

- CSS 2.1 (2009)

- CSS 3 (under construction)

Hint: Use browser compatibility tables when you plan for a larger audience

Syntax of CSS declarations A stylesheet is a set of rules (also called rule sets) that describe how to render XML or HTML elements. Each rule has two parts:

- The selector (before the curly braces) defines to which elements a rule applies

- The declaration block (inside the curly braces) defines rendering, i.e. values of CSS properties

selector { property:value; }

Each declaration block.

- should include at least a property names and a value, separated by a colon (:)

- Several property:value pairs must be separated by a semi-colon (;)

Here is a CSS for HTML or XHTML example:

h1 { color: red }

p { font-face: Verdana, sans-serif ; font-size: 12pt}

h1, h2, h3 { color : blue }

h1.Chaptertoc, h2.PeriodeTOC, h2.ExerciceTOC, h2.SectionTOC {

display: block;text-indent: 30pt;

text-align: left; font-size: 14pt;

font-weight: Bold; font-family: Times;

}

As you can see h1 is defined more than once and the ground rule is that the last definition will apply, e.g. in our example, h1 will be blue.

Comments

In computer speak, comments are lines of code that (usually) ignored by the computer. Coders use comments to document the code. In CSS, comments are inserted between /* .... */ and may extend over several lines. But don't use comments within the braces of the property declaration.

/* I love HUGE titles */

h1 {size: 50px ; }

What does Cascading mean

Cascading refers to the fact the rendering properties of a single element and its attributes may "trickle down from many sources.

- More than one rule may define properties of an element

- Most CSS properties of a parent element will be inherited

According to SitePoint's Cascade article (which at some point you might read in detail), the CSS cascade involves these four steps:

- For a given property, find all declarations that apply to a specific element, i.e. load all CSS files that are declared for a given media type

- Sort the declarations according to their levels of importance, and origins. Other than the HTML page, the user plus the navigator (user-agent) also can add stylesheets. E.g. if you install the Greasemonkey extension to Firefox, you may install JS client-scripts that can override the original CSS. Declarations are sorted in the following order (from lowest to highest priority):

- user agent declarations

- normal declarations in user style sheets

- normal declarations in author style sheets

- important declarations in author style sheets

- important declarations in user style sheets

- Sort declarations with the same level of importance and origin by selector specificity. Typically, inline element specifications have the highest specificity. I.e. if the default style of a paragraph is normal, then it is logical that a span defining a bold part has higher priority.

- Finally, if declarations have the same level of importance, origin, and specificity, sort them by the order in which they are specified; the last declaration wins.

Cascading can be very tricky, however this is not the case for the kinds of simple style sheet a beginner or myself would write ...

Associating styles with HTML

There exist three main methods for associating style with HTML:

- Use one ore more external CSS files

- Use the HTML style tag.

- Use the HTML style attribute (inline styling)

You also can combine all three.

Associating CSS files with an HTML file

A CSS file is associated using the link element. In the most simple case, we just use the link element and need to define three attributes:

- rel defines the type of file. Its value is "stylesheet"

- hred defines the link to the URL of the CSS file

- type defines the kind of stylesheet, for CSS use "text/css".

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css-intro.css" type="text/css">

Definition of Mediatype

- media can define a stylesheet for a different medium, e.g. a printer

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css-intro-print.css" type="text/css" media="print">

You may include several links, the last rule found will apply. Typically, in portalware, several stylesheets are loaded.

Example from Zikula:

<link rel="stylesheet" href="themes/TecfaBreeze/style/style.css" type="text/css" media="screen,projection" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="modules/News/pnstyle/style.css" type="text/css" />

<link rel="stylesheet" href="javascript/style.css" type="text/css" />

I.e. if your HTML

Example from Moodle (styles are dynamically generated with PHP files): <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="theme/standard/styles.php" /> <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="theme/standardblue/styles.php" />

Importing style sheet files within a CSS file

To import a CSS file within another CSS you may use a so-called at-rule.

@import url (base.css);

Important: These at-rules must be define on top of a CSS file, i.e. before you define any CSS rule. Also at-rules are buggy with IE 6/7.

These at rules can be used for other purposes, e.g. to specify that one or more rule sets in a style sheet will apply only to certain media types (see below)

Alternate stylesheets

There exist three methods for defining alternative stylesheets

(1) You may define alternative stylesheets, e.g. one that uses a bigger font for people with bad eyesight. Most browsers allow users to select from alternative stylesheets.

Now, these stylesheets have to be linked in a special way (unless they are media specific).

<link rel="alternate stylesheet" type="text/css" media="screen" title="Friendly fonts" href="friendly.css" />

<link rel="alternate stylesheet" type="text/css" media="screen" title="bigtype" href="big.css" />

In addition, you should provide JavaScript code that will allow the user to switch style (a typical user may not know how to do this manually). A older very popular and free example is available from AlistAPart. A more sophisticated 2004 version also.

(2) The @import at-rule allows to specify a media type, i.e. you may use this strategy to load various CSS variants from a single CSS file.

@import url(print-style.css) print;

Also, you often will find the @import CSS at-rule as replacement of the HTML link tag. E.g. the two following expressions are identical:

<style type="text/css">@import url(css-intro.css)</style>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="css-intro.css" type="text/css">

(3) Media-specific alternatives also can be defined within a single style sheet using the @media at-rule.

@media print {

body {

padding: 3cm;

}

@media screen, projection {

body {

padding: 1cm;

}

}

Style definitions with the HTML style tag

CSS rules may be inserted within the HTML STYLE tag (must be in lower case in XHTML). Generally speaking you should avoid this method, because if you define your CSS with an external file you can use it with many other HTML pages.

HTML code that is generated on the fly often includes style definitions at page level, but that should be avoided too, since it is better policy to include all stylesheets in a special directory structure from where the programs then can load them in. Personnally, we only use this type of styles for teaching purposes (CSS code sits next to HTML code) and in situations where were we only want to carry a single file, e.g. in collaborative writing via email...

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//IETF//DTD HTML 3.2//EN">

<html>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Simple CSS demo</TITLE>

<STYLE type="text/css">

body {background: white; font-family: Arial, sans-serif;}

H2 {color: blue;} /* will be overriden by an other rule below */

H2, H3 {font-family: Arial, sans-serif;}

H2 {color: red; text-decoration: underline;}

P.intro {color: blue; margin-left: 4em; margin-right: 2em;}

.default {margin-left: 2em;}

</STYLE>

</HEAD>

.....

In true XHTML (served as "application/xhtml+xml"), the contents of style must be inserted within a CDATA declaration. Otherwise, you will get an error when you validate your code.

<style type="text/css"><![CDATA[

body { .... }

h1 ....

......

//]]></style>

XHTML is XML. Inside an XML tag, you can't have another markup language like CSS. Put simply, <![CDATA[ ... ]]> tells the XML parser not to look "inside". If you just use XHTML syntax, i.e. serve the file as HTML so that IE can understand it, the CDATA section is not needed.

Inline HTML style definitions

Inline HTML style definitions like page level style definitions should be generally avoided for the same reasons, i.e. maintenance costs and division of labor. Therefore again, use it only for testing and demonstration purposes.

Most (or all?) HTML tags allow the use of a style attribute like in the following example. As you can see there is neither a selector nor curly braces. For obvious reasons, you only will define property-value pairs separated by a semi-colon (;).

Example:

<p style="color:green;font-weight:bold;">Green fat grass</p>

CSS woes

Despite the global acceptance of CSS, it took many many years before CSS 2 (defined in 1998) worked reasonably well. E.g. it took Microsoft over 10 years to get there (IE 8). In the past, in particular in the late nineties, page styling was a nightmare. In the early 2000s simple use of CSS just worked fine, but sophisticated designs didn't and web designers had to use various ugly tricks. Web designers who have to code sophisticated pixel-precise code for all browsers on the market still have to do this, but "normal" people now can quite safely ignore browser specific code. As of summer 2009, you just should avoid using CSS 2.1 and stick to CSS 2.0.

The bottom line to do so is simple. Use correct detailed HTML declarations on top of your HTML files.

Dealing with bad implementations

“Quirks mode and strict mode are the two "modes" modern browsers can use to interpret your CSS. [...] when standards compliancy became important browser vendors faced a tough choice. Moving closer to the W3C specifications was the way to go, but if they’d just change the CSS implementations to match the standards perfectly, many websites would break to a greater or lesser extent. Existing CSS would start to show odd side effects if it were suddenly interpreted in the correct way. [...] In other words, all browsers needed two modes: quirks mode for the old rules, strict mode for the standard. IE Mac was the first browser to implement the two modes, and IE Windows 6, Mozilla, Safari, and Opera followed suit.” (Quirksmode.org, retrieved 17:16, 8 September 2009 (UTC)).

There are two strategies for dealing with compatibility issues:

- You just don't care and develop according to recent standards (e.g. I can do this)

- You spend a few days documenting yourself making sure that you will not adopt strategies that will break in future browsers. Below we just provide a few hints.

The ground rule for modern browsers is the following:

- Most doctype declarations will trigger "strict" mode in most browser. This is a sort of commonly accepted heuristic adopted by browser makers and definitly not standardized. DocTypes are not about style ...

- In addition, always close all tags (even if you work with HTML 4x transitional !)

Henri Sivonen provides a detailed explanation, plus an overview table that show what various browsers do with various doctype declarations. We shall just mention here that most of the following kinds of declarations will trigger "strict" or almost strict CSS in most browsers:

- All XHTML DTDs

- The HTML 5 declaration (<!DOCTYPE html>)

- HTML 4 declarations that include a URL

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN">

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.1//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml11/DTD/xhtml11.dtd">

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Strict//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-strict.dtd">

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

Checking the mode in your browser

- Firefox: use the command View/Page Info

- IE: type javascript:alert(document.compatMode)

So what DTD declaration should you use ?

- If you already trust HTML 5 (this is the strategy the google search page adopts)

<!DOCTYPE html>

- Standard 4.01 HTML strict

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/strict.dtd">

- Transitional 4.01 HTML

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd">

- XHTML 1.1 strict

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.1//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml11/DTD/xhtml11.dtd">

- Alternatively, no DocType: XML doesn't need a DocType and the HTML version is defined in the namespace declaration

- XHTML transitional

<!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD XHTML 1.0 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/xhtml1/DTD/xhtml1-transitional.dtd">

- Alternatively, no DocType: XML doesn't need a DocType and the HTML version is defined in the namespace declaration

Internet Explorer hacks Since IE 6 and 7 were know for faulty CSS implementations, you may use the following HTML comments: Note: IE 8 is fine, therefore we suggest that you simply ignore IE 6/7 problems (unless you will have to desing a website for a very large audience). IE8 has four modes: IE 5.5 quirks mode, IE 7 standards mode, IE 8 almost standards mode and IE 8 standards mode. Understanding under which conditions IE falls into what mode is really complicated. according to Henri Sivonen “The choice of mode depends on data from various sources: doctype, a meta element, an HTTP header, periodically downloaded data from Microsoft, the intranet zone, settings made by the user, settings made by an intranet administrator, the mode of the frame parent if any and a UI button togglable by the user. (With other apps that embed the engine, the mode also depends on the embedding application.)”. The lucky thing is that IE8 uses doctype sniffing roughly like other browsers if you did not do anything of the above, i.e. if you own a "normal web site" and create "normal standards-compliant" pages.

Another strategy that you see a lot when you look a computer generated pages (i.e. in portalware) is to use HTML conditional comments that only work in Explorer on Windows. You can read more at Quirksmode. Example that shows how to load specific stylesheets for specific IE versions.

<!--[if IE 7]>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="theme/standard/styles_ie7.css" />

<![endif]-->

<!--[if IE 6]>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="theme/standard/styles_ie6.css" />

<![endif]-->

Have a look at the styles used by this wiki page. In Firefox 2 and 3 use menu View-> Page Source or type ctrl-U. In IE 8, right click or use the Page menu and then "View Source". Anyhow, I suggest not to adopt this kind of informal markup, unless you really do have trouble creating good looking contents for older IE browsers.

The HTML div and span elements

Lets recall from the HTML and XHTML elements and attributes tutorial that we may roughly distinguish between block and inline elements. Basically block elements start on a new line (e.g. titles, paragraphs or lists) and inline elements are inserted on the same line (e.g. some bold text or a picture).

CSS designers often use two specific HTML elements to define "custom" blocks and inline regions. <div>...</div> allows to define a block (that most often includes a region of normal HTML block elements) and <span>...</span> to define a region within a block element. Therefore, we shall introduce these two elements again with examples.

The div tag

You may look at the source of a Mediawikipage (e.g. a Wikipedia or EduTechWiki page) to understand how portals might the structure contents of a page (if you are reading this online, view the source"). Simplified, a page looks like this.

<div id="globalWrapper">

<div id="column-content">

<div id="content">

<div id="bodyContent">

... lots of other nested divs inside, e.g.

<div class="printfooter">

</div>

</div>

</div>

<div id="column-one">

... lots of other nested divs inside, e.g.

<div class='generated-sidebar portlet' id='p-navigation_and_help'>

<h5>navigation and help</h5>

<div class='pBody'>

<ul>

<li id="n-Mainpage"><a href="/en/Main_Page">Main Page</a></li>

<li id="n-about"><a href="/en/EduTech_Wiki:About">About</a></li>

<li id="n-Help"><a href="/en/Help:Contents">Help</a></li>

......

</ul>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

</div>

This many divs allow to position and style each "box". E.g. all the boxes of class "generated-sidebar portlets" are positionned to the left and the "pBody" class is used to draw the contents of these little menu boxes.

Now, to make it a bit simpler. If you plan to style a whole section of your HTML in a given way, e.g. make it blue, then just wrap a div tag around. But make sure to respect the HTML "boxes within boxes" principle.

Good:

<div class="intro">

<h2>Introduction</h2>

<p>I am happy to introduce CSS now.</p>

<p>CSS was introduced .... </p>

</div>

<h2>Next section</h2>

Bad:

<div class="intro">

<h2>Introduction</h2>

<p>I am happy to introduce CSS now.</p>

<p>CSS was introduced ....</div> </p>

<h2>Next section</h2>

We shall se below, how we then could make the whole "into" region blue.

The span tag

The span tag has the same function as div tag inside a block element.

Here is a little example that shows how to span with inline styling.

<p> <span style="font-weight:bold;">This article <i>or</i> section is a stub</span>.

A stub is an entry that did not yet receive substantial attention .....</p>

Introduction to CSS 2 selectors

A selector identifies the element(s) that we will style with properties.

CSS 2 selectors work for HTML, XHTML and any text-centric XML (XML needs a navigator that supports at least partically CSS 2.0 and XML)

Simple selectors for HTML elements

Selection of an element

- element

example:

dd {

display: list-item;

list-style-type: decimal;

}

You may start learning CSS just by styling various HTML elements, e.g. you may decide to change the font of all title elements. I.e. instead of selecting just one element you may include a list of elements.

h1,h2,h3,h4 {font-family: Arial;}

The universal default selector

The universal selector matches any element type. As we will see later you then can add pseudo-selector components to it.

* {

font-family: Arial /* By default all fonts will be Arial */

}

Warning: The universal selector doesn't work in IE 6 and also may have problems in IE7. A work around is to style the html or the body element.

Children, cousins and other family

You also may define styles according to the position within which they may be found within a a text. E.g. you may style differently a p element inside a li element than a "normal" p element as you can see in the example just below.

Selection of a child element:

- mother_element > child_element

Example:

p { line-height: 1.5 }

li > p { line-height: 1.3 }

Selection of descendant element (child, great-child, etc.):

- mother_element element

Example:

li p { .... }

All p elements that sit somewhere at any level of nesting inside a li tag will be affected

Combinations: Example:

DIV OL>LI P

Selection of siblings (elements next to each other sharing the same parent)

- sister_element + sister_element

example:

H1 + H2 { margin-top: -5mm }

Selection of elements through their attributes

selection of an element that has a certain attribute

- element[attribute]

example:

Title[status] { color: blue; }

(all titles that have a status attribute are rendered in blue )

Selection of an element that has an attribute with a given value

- element[attribute="value"]

example:

div [status="draft"] { color: red; }

selection of an element that has an attribute with a value in a space separated list

div[status~="draft"] { color: blue; }

This selector would for instance select the following HTML tag:

<div status ="draft ugly important">

but not:

<div status ="ugly-draft">

There are even more sophisticated attribute selectors, but we have shown you enough with respect to a beginners tutorial.

Class selectors

Frequently designers define a class value for various HTML elements in a text. Let's show this with an example. In the HTML fragment below, we use two p elements. The first is a normal paragraph. The second includes a class="draft" attribute and value.

<p>I now got over a decade of CSS experience and understand fairly well how CSS works and how it can be used</p>

<p class="draft">But on the other hand I really don't care much about style</p>

On the CSS side we now could render the second paragraph in a different way. E.g. define a rule like this:

p.draft { color: red; };

A class selector is just an abbreviation for the attribute selector introduced above. E.g. we could have written the same rule as:

p [class="draft"] { color: red; };

Now let's assume that we got other HTML elements with a class="draft" and we want them all to be red. In that case we just could use the following syntax:

.draft { color: red; };

Alternatively, this could have been written with the Universal selector spelled out:

*.draft { color: red; };

The ID selector

In SGML and XML and therefore in HTML and XHTML 'ID' attributes allow to uniquely define an element in a given page. An ID attribute is declared as ID in its document type definition (DTD) or similar. E.g.

- in HTML, the ID attribute is id or ID

- in XHTML, the ID attribute is id

- in your own XML, it can be anything of course.

The ID selector is usually used for complex CSS layouts, in particular the positioning of boxes that include menus and other items that are not in the main flow of the text. Each of these boxes must be uniquely positionned and there have a unique identifier.

#mainmenu { ..... }

E.g. for HTML code like this:

We could use CSS like that:

See the CSS positioning tutorial for details.

Cascading and inheritance

Rule ordering

- (Roughly speaking): the last rule found will win.

- E.g. if you define text color in more than one place, the color: property found in the last rule encountered will be used

Inheritance of properties from parents

- Child elements usually inherit properties from the parent elements !!!

- If you don’t like this you have to change explicitly these properties

- Inheritance of properties

XML

<title>Here is a title</title> <para>Here is a paragraph>

CSS

section {font-family:Arial}

title {font-familiy:Helvetica}

/* para will inherit font-family from section, i.e. Arial */

Summary of CSS2 selectors

| Pattern | |

| * | Matches any element. |

| E | Matches any E element (i.e., an element of type E). |

| E F | Matches any F element that is a descendant of an E element. |

| E > F | Matches any F element that is a child of an element E. |

| E:first-child | Matches element E when E is the first child of its parent. |

| E:link

E:visited |

Matches element E if E is the source anchor of a hyperlink of which the target is not yet visited (:link) or already visited (:visited). |

| E:active

E:hover E:focus |

Matches E during certain user actions. |

| E + F | Matches any F element immediately preceded by an element E. |

| E[foo] | Matches any E element with the "foo" attribute set (whatever the value). |

| E[foo="warning"] | Matches any E element whose "foo" attribute value is exactly equal to "warning". |

| E[foo~="warning"] | Matches any E element whose "foo" attribute value is a list of space-separated values, one of which is exactly equal to "warning". |

| ="en"] | Matches any E element whose "lang" attribute has a hyphen-separated list of values beginning (from the left) with "en". |

| DIV.warning | HTML only. The same as DIV[class~="warning"]. |

| E#myid | Matches any E element ID equal to "myid". |

CSS properties

Syntax of CSS property definitions

- property:value;

- property:value,alternative_value1,alternative_value2,...;

Most important typographic element types:

(1) Blocks, i.e. elements that should start a new paragraph

HTML examples: <p>, <h2>, <div>

(2) Lists and list elements

HTML example: <ul>, <ol>, <li>

(3) Inline elements

HTML examples: <b>, <strong>, <span>

(4) Tables Of course, you also can decide to use absolute positioning to place elements ...

The Display attribute

By default, HTML will display an element as either a block, list element or inline. But you are free to change this.

Raw XML (e.g. your own) doesn't include any styling information. Therefore, the first operation when dealing with XML is to define the display property for each element

Examples that work with most browsers:

display: block; display: inline; display: list-item;

Comments

CSS Comments begin with the characters "/*" and end with the characters "*/". They may occur anywhere between tokens, and their contents have no influence on the rendering.

- Comments may not be nested.

Example:

/* Paragraph elements */

para {display:block;} /* para elements are blocks */

Font properties

| font-family: Helvetica; | |||

| font-family: serif; | |||

| font-size: 14pt; | |||

| font-style: italic; | |||

| font-weight: 500; | |||

| font-weight: normal; | |||

| font-weight: bold; |

- Text alignment

|

|

text-align: left; | |

| text-align: center; | |||

| text-align: right; | |||

| text-align: justify; | |||

| text-indent: 1cm; | |||

| line-height: 14pt; | |||

| line-height: 1.2; |

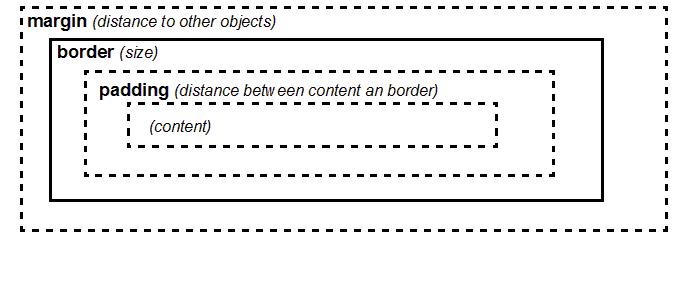

CSS Box structure

Each CSS element is a box

There are properties for each of these components and for some properties, there are shortcuts

Borders, margins and colors properties (there are more)

| body {margin:1cm;} | |||

| p {margin-top:10px;} | |||

| h3 {margin-bottom:3pt;} | |||

| img {margin-left:50px;} | |||

| p.citation {margin-right:10pt;} | |||

| p {border:5px;} | |||

| h1 {border-top:0.2cm;} | |||

| p {border-style:solid;} | |||

| h1 {border-style:double;} | |||

| p {padding: 5px;} | |||

| #menu {color:#000000;}

body {color:blue;} | |||

| section, h2 {background:blue;} |

Printing with style

CSS 2 is not really made for printing. However in modern CSS 2 browsers, there are some tricks.

Firstly, as we already explained you may use alternative stylesheets of the @media at-rule to define specific styles for printing. In particular, you may get rid of all menus and other stuff that you don't need on paper.

In addition, the @page at-rules allows to specify margin values for the "page" box.

Simple example:

@page {margin: 2.5cm}

Example that sets margins for various page types:

/* The default rule set a 2.5cm margin on top,bottom,left,right */

@page { margin: 2.5cm; }

@page :left { margin-left: 3cm; } /* left pages */

@page :right { margin-right: 3cm; } /* right pages */

@page :first { margin-top: 5cm; } /* first page has an big top margin */

If your stylesheet doesn’t display as it should

Validate your CSS (submit the CSS file): http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator/

Typical syntax mistakes (easy to detect)

- Missing punctuations in property declaration (":" or ";" or ",")

- misspelled property names

- missing brace { ....

Syntax mistakes that are hard to find:

- Check spelling of element names, the on-line CSS validator will not detect this !

Compatibility issues:

- Check compatibility of your browser or at least check with Firefox or IE8. A very good web site is Quirksmode.

- As of summer 2009, you might avoid CSS 2.1 and stick to CSS 2.0. E.g. IE8 has some problems with a few 2.1 selectors and properties. In particular (I don't know why) CSS 2.1 selectors won't work with XML for CSS tutorial.

Logical issues:

- Remember that most properties are inherited from parent elements and that the last rule defined wins. I.e. the rule that will define what you get is not the one that you are looking at ...

- If you use several stylesheet files, make sure to load these in the right order

Resources on the web

See CSS links for tutorials and other interesting links. Here we just include a short selection

- Online Manual

- CSS Reference at SitePoint

- Standards

- http://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/ (CSS page of the W3C)

- http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2/ (CSS 2 specification)

- Compatibility tables

- http://www.quirksmode.org/css/contents.html (consult this for IE 6/7! in particular)

- CSS Validator (use it please !)

- http://jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator/