Cultural competence

Introduction

Cultural competence or intercultural competence or cross-cultural competence or being able to cope with cultural diversity is becoming increasingly important.

Cultural competence is a form of literacy. Note that the term "cultural literacy" often seems to refer to simple facts knowledge (history, geography, etc.).

With increasing cultural diversity as a result of globalization, intercultural competence (IC) to interact and co-exist in multicultural environments is recognized as being very important. (Corder and U-Mackey, 2015).

Heyward (2002) cited by Deithl & Prints (2008), defines intercultural literacy as the competencies, understandings, attitudes, language, proficiencies, participation and identities necessary for effective cross-cultural engagement.

Culture itself is difficult to define. Billmann-Mahecha (2003) [1] defines it [translated] in the following way: “Culture can be characterized as a character, knowledge, rule and symbol system that structures on on hand the human action space, and on the other hand is constructed and altered through the implementation of actions and their practice.” In more simple words, it is something that guides our activities, but that is also reshaped by those.

Cultural and cross-cultural psychology

Cultural psychology, after the rise of cognitivism, seems to have become a somewhat forgotten science (Allolio-Näcke, 2005)[2]. On the other hand, cultural dimensions are central to ethnology, anthropology, (cognitive) linguistics, literature critique, etc., i.e. disciplines that put emphasis on "sense" and "meaning".

According to Doris Weidemann (2001)[3] , “investigation of intercultural interactions has demonstrated that individual psychological processes show distinct cultural patterns and, more important, that communication across cultural gaps often meets with difficulties.” She also adds, that “Communication across cultural divides is usually described as difficult and often results in misunderstandings and failure to achieve individual or even common goals. This is especially true for persons transferring to a different cultural context, as overseas students, expatriate managers or immigrants do, and adaptation to the new cultural environment can be frustrating and painful.”

In that context, literacies (not just cultural ones) cannot be compared in an abstract way or with respect to one culture, but rather as a predictor for a successful life in a given culture. This principle applies for example when comparing school systems. “Nur in dem Falle, "dass innerhalb eines jeden Landes, die erfassten Kompetenzen zur Vorhersage einer erfolgreichen Lebensführung beitragen", könnte das literacy-Konzept als tertium comparationis fungieren. In vielen Ländern aber spielt es keine bzw. nur eine untergeordnete Rolle, so dass "der Ausgang einer solchen Validitätsprüfung wahrscheinlich zu einer kulturellen Gruppierung der Funktionalität der Grundkompetenzen führen wird";” (Hermann-Günter Hesse, cited by Allolio-Näcke, 2005).

Simple models of cultural difference

Models of cultural difference are popular in management and management education since corporations do have to deal with different cultures.

Hampden Turner and Trompenaars (1993)

According to Darlene Brannigan Smith et al. in the Seven Cultures of Capitalism, Hampden Turner and Trompenaars (1993:11) suggest that different countries champion different value propositions for creating effective organization.

- Universalism (call for universally applicable law and order) vs. particularism (allow for personal indulgence and idiosyncrasies),

- anlyzing (demand for facts and attention purely on the bottom line) vs. integrating (viewing everything within the context),

- individualism (applaud individuals for singular performance) vs. communitarianism (organization, groups and community above else),

- inner directed (self-starter) vs. outer-directed (approaching groupthink) orientation,

- time as sequence (time is money) vs. time as synchronization (all for one),

- achieved status (working hard to achieve) vs. ascribed status (status because of power), and

- equality (all get an even break) vs. hierarchy (some people are more important because of their hierarchical authority).

Hofstede

Hofstede distinguishes five or six dimensions of national cultures. Each of these is defined by a list of criteria. Hofstede (2011) [4], summaries these dimensions:

1. Power Distance, related to the different solutions to the basic problem of human inequality;

2. Uncertainty Avoidance, related to the level of stress in a society in the face of an unknown future;

3. Individualism versus Collectivism, related to the integration of individuals into primary groups;

4. Masculinity versus Femininity, related to the division of emotional roles between women and men;

5. Long Term versus Short Term Orientation, related to the choice of focus for people's efforts: the future or the present and past.

6. Indulgence versus Restraint, related to the gratification versus control of basic human desires related to enjoying life.Wikipedia, based on Hofstede (2011) [4] provides a nice summary.

National cultures are not identical to organizational or individual cultures. E.g. within a same town one can find companies that adopt a very different organizational-cultural model. The same is true for individuals. However, national (or even supra-national) cultures doe influence organizational and individual ones.

Instruments to measure cultural diversity and compentency

World Values Survey

According to Wikipedia, “The World Values Survey (WVS) is a global research project that explores people’s values and beliefs, how they change over time and what social and political impact they have. It is carried out by a worldwide network of social scientists who, since 1981, have conducted representative national surveys in almost 100 countries. The WVS measures, monitors and analyzes: support for democracy, tolerance of foreigners and ethnic minorities, support for gender equality, the role of religion and changing levels of religiosity, the impact of globalization, attitudes toward the environment, work, family, politics, national identity, culture, diversity, insecurity, and subjective well-being.”

The WVS started in 1981 and is now governed by the World Values Survey Association, based in Stockholm.

Teaching intercultural literacy

General principles

Deborah Corder and Alice U-Mackey (2015) [5] argue that educating intercultural literacy is very challenging. Cognitive aims (e.g. learners being able to pass an exam) can be met, however, meeting affective and behavioral goals might be much more difficult. According to the authors, “research shows that the development of IC is a complex process that involves cognitive, metacognitive, affective and behavioural development, and has to be intentionally developed over time (Ehrenreich 2006; Stier 2006; Crossman 2011; Deardorff 2011). As Perry and Southwell (2011) and Witte (2011) point out, there is increasing evidence that the normal classroom or lecture context with a cognitive orientation alone cannot provide the environment for learners to develop the necessary competencies. Nor will IC automatically develop by just encountering other cultures whether in the classroom, through study abroad, overseas holidays, the workplace or social settings.”

Intercultural diversity is an important component of global citizenship. Vadura (2007: 17) argues that “The knowledge, skills and values that international studies graduates gain need now more than ever to reflect understanding of social responsibility and cultural inclusivity, embodied in the concept of global citizenship.”

Johanna E. Crossman led a qualitative study that aimed to “discover how undergraduate and culturally diverse students experienced a collaborative, international, online, experiential project to learn about intercultural communication. Student participants in the study endorsed experiential learning in culturally diverse groups about intercultural communication through intercultural communication.”. The study involved students from Australia, international students from Asia (in Australia) and students from the Netherlands. The task was to “to respond to a case study that concerned a franchisor in Australia considering two expressions of interest from potential franchisees in the Netherlands and Hong Kong.”. More specificially, members of the these three populations were required to act as "communication consultants" to advise the fanchisor of any potential intercultrual communication implications between the Australian organisation and the Dutch and Asian franchise. In other words, each type of student had to play and reflect upon his own cultural inheritage.

In this context, the author found that “learning about intercultural communication through intercultural communication is a powerful activity that responds to the need for learning approaches that internationalise the business curriculum in universities and develop global citizenship. The capacity of the experiential project appeared to engage students in ways that seemed to be perceived as authentic and relevant to their lives and work. The study has also illuminated how participants try to make sense of intercultural communication by juxtaposing personal experience with theoretical literature. Whilst stereotyping did occur, the observation can be used in the design of future activities so that the potential for meta-cognitive approaches can be developed further through asking questions about what stereotyping is and how, why and under what circumstances individuals might engage in it, particularly when tension and conflict exists in intercultural communication and indeed, culturally diverse learning contexts.”

Strategies and tactics

- Roles games

- Cultural infusion activities, e.g. scavenger Hunts

Elicitation and representation of cultural representations

Structure Formation Technique

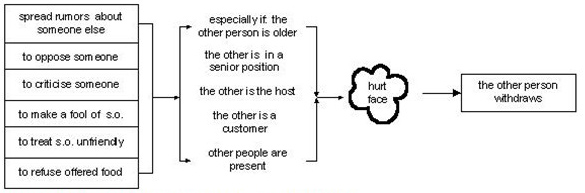

Weideman's (2001) [6] study focuses on subjective theories hold by German Immigrants in Taiwan and that can be verbally explicated and reconstructed by way of dialogue between researcher and participant. The research method goes through the following steps:

- A semi-standardized interview that will try to elicit the contents of the subjective theories

- A visualization of the theory structure ,using representational rules of the Heidelberg structure formation technique, (Heidelberger Strukturlegetechnik, SCHEELE & GROEBEN, 1988)

Based on this Heidelberg structure formation technique, she developed a set of interview questions and rules for representing the theory.: “a differentiation was made according to the outcome of actions (face gained or face lost) and the person concerned (self or other).” The combination of these two dimensions will define four semantic fields, namely a) to lose face, b) to gain face, c) to hurt the other person's face, d) to give the other person face.

Results then can be represented graphically, for example like this:

Arts-Informed Research

Over the last decade, a growing number of social scientists have become interested in visual methodologies. On could distinguish between "researcher created", "respondent generated" and "found" visual data. Visual arts can be found in all three. [7]

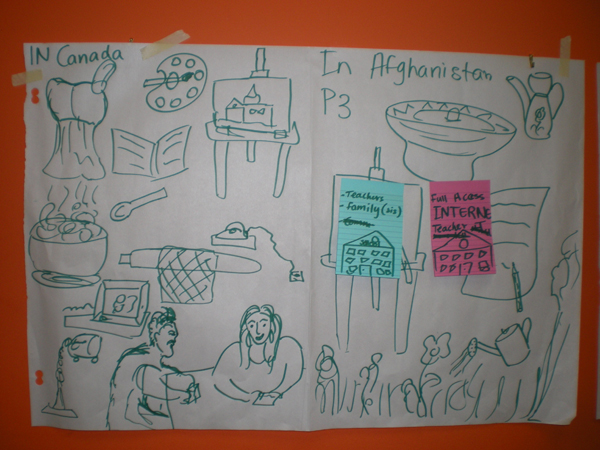

Guruge et al. (2015) [8] describe an arts-informed technique “to understand the changes in refugee youth's roles and responsibilities in the family within the (re)settlement context in Canada. The study involved 57 newcomer youths from Afghan, Karen, or Sudanese communities in Toronto, who had come to Canada as refugees. The data collection method embedded a drawing activity within focus group discussions.”

This study also included eight refugee youth peer researchers from the three communities. In line with community-based participatory research principles, {{quotation|Peer researchers received three months of research training and were actively involved in paid capacity in all phases of the study, including research design, data collection, data analysis, and writing. Guruge et al. (2015:[14]) describe the elicitation process as follows:

Each participant was invited to draw two pictures:

- one depicting pre-migration roles and responsibilities,

- and the second depicting post-migration roles and responsibilities.

A key lesson learnt was that adequate time and opportunities must be given to participants to (1) create the drawings, (2) to interpret and discuss the drawings and (3) to complete or change the drawings as a result of group discussions. Facilitators must attempt to clarify and expand links between drawings and discussions.

According to the authors [paragraph 38], “The multiple data collection methods (i.e., drawings and individual reflections on them, and focus group discussions) we used in this study were complementary: the drawings provided unique insights into certain aspects of their lives. For example, the magnitude of the difference in youth's (built and natural) environments came up in the drawings that were not discussed in the focus groups. The sense of cohesion versus scattered and chaotic patterns in the drawings is also interesting. On the other hand, the focus group discussions provided unique information on other aspects of their lives, such as racism. In addition, the drawings also provided more contextual information that enriched the understanding gained from the focus groups.”

Data analysis and interpretation involved several levels of analysis and was based on participant's own explanations:

- a reflective dialogue between each participant and his own drawing

- a group dialogue concerning all the drawings of the group

- reflections of the peer (refugee youth) researchers from each group in response to questions about (1) and (2) from the rest of the research team

- the research teams reflections across the three groups

A list of themes and supporting excerpts was finally established in the form of a table.

Somewhat similar research was conducted by Frey and Cross (2011) [9] on overcoming poor youth stigmatization and invisibility through art. Initially, a more traditional plan was to conduct interviews with various stakeholders, then creating focus groups, and finally a joint work on a common video to trigger dialogue with other actors. The team then found out the dramatization and video could (and did) have a more important role “We discovered that the inclusion of dramatization and video had three main effects: first, they favored the involvement of the young men and women; second, they allowed them to share their experiences, formerly blocked by stigmatization processes; third, they were a potent instrument to make their perspectives visible to other social actors concerned by this problematic (teachers, government officers, parents).” Frey and Cross (2011:69)

Tristan Bruslé's (2010) [10] research examines the place that Nepalese immigrant workers occupy in Qatar. Visual images, mainly photographs, are use as one of the research tools to illustrate the divided nature of society.

“I have tried to put forward the hypothesis that photographs are not just an illustration, but that social realities can indeed be understood through pictures. The building of places, from collective spaces to very private ones, clearly stands out in the pictures. The use of pictures to analyze social and spatial division in Qatar has enabled me to grasp some realities that I had either overlooked or not fully understood. While carrying out fieldwork, and particularly new fieldwork, the researcher is continually bombarded with a flow of information, making it at times difficult to focus on everything of interest. Pictures are therefore a way of focusing on detail, especially in a migrant's room, which might not necessarily have been studied while talking to migrants. Looking at pictures taken in an almost random way is also a way of reactivating one's memory. Distant places, emotions and memories come to life when perusing pictures. Things that were not first noticed when the photograph was actually taken, but were "discovered" thanks to a careful study and comparison of pictures, come across as important and make sense. A juxtaposition of scenes has helped me identify common points between places. Moreover, pictures have helped me show the different levels of spatial segregation, from the town to the migrant's bed. Images of walls and of physical separation may prove to be speaker louder than mere words in making the reader realize what segregation really is. Indeed, pictures can play the role of backing up research and be a valuable tool in that they convey large amounts of information that would sometimes be harder to explain verbally.” (Bruslé's, 2010, [29])

Map making

Olga den Besten (2010) [11] studied social and spatial divisions (urban segregation). Her study “explores children's and young people's experiences in two socially contrasted neighbourhoods in Berlin through subjective maps drawn by the children.”

“Children were asked to produce two maps: first, to draw their way home from school and all the objects that attracted their attention on the way. This task was chosen because all the children went to school, so the way home from school was their everyday, routine trajectory (see also ROSS, 2007). Coming back home from school was chosen because of the supposedly more relaxed, unhurried character of this trajectory and more opportunities for deviations from this way, like, for example, popping in to shops or playing in a park after classes. Second, the children were asked to draw their "neighbourhood" or "territory", i.e. a city area which they knew rather well and where they "felt at home". This drawing activity was done at school during one lesson.” (den Besten: 2010: [13]).

In addition, children were asked to place four types of emoticons on the maps: (1) A heart symbol to mark places they like, (2) a big dot for places where they hang out, (3) a cross inside a circle for places they disliked and (4) a square for places they fear.

Results showed that the children's socio-spatial worlds were different in the two segregated areas of the city. Generally, drawings from children of the advantaged area are comparatively more elaborated, show a larger space, more places for activities, a denser network of friends, and so forth. This also reflects the situation that advantaged children have more access to extra curricular activities and therefore for personal development.

A map of her "subjective territory" by a 13-year-old German-American girl from the school in Zehlendorf. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[11]

Drawing 3a (by a Turkish boy aged 14 in Kreuzberg) features a youth club and a football field. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[11]

Measuring cultural literacy

Besides trying to represent, summarize, visualize and compare different cultural representations, research also attempts to quantify cultural competence with psycho-metric tools.

Technologies for cultural literacy

According to Anstadt (2015), an environment like second life has several affordances:

- The ability to role play simulations without compromising the identity of the individual. Yet at the same time there, is a relationship between users virtual lives and their real lives.

- A simulated environment offers the potential for a range of experiences that is not available in "real live", including connecting with people that otherwise cannot be met.

Links

- Some Wikipedia articles

- Cultural competence (Wikipedia)

- Intercultural competence

- Intercultural communication principles

- Intercultural relations

Bibliography

Cited

- ↑ Billmann-Mahecha, Elfriede (2003). Kulturpsychologie. In Psychologie von A-Z. Die sechzig wichtigsten Disziplinen. München: Spektrum.

- ↑ Allolio-Näcke, Lars (2005). Wie viel Kultur verträgt die Psychologie? Tagungsbericht: 100 Jahre Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie [34 Absätze]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Art. 11, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0503111.

- ↑ Weidemann, Doris (2001). Learning about "face"—"subjective theories" as a construct in analysing intercultural learning processes of Germans in Taiwan. Forum Qualitative Socialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(3), Art. 20, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0103208 [Date of access: March 10, 2008].

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- ↑ Corder, Deborah. & U-Mackey, Alice. (2015). Encountering and dealing with difference: second life and intercultural competence, Intercultural Education, DOI:10.1080/14675986.2015.1091213

- ↑ Weidemann, Doris (2001). Learning about "face"—"subjective theories" as a construct in analysing intercultural learning processes of Germans in Taiwan. Forum Qualitative Socialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(3), Art. 20, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0103208 [Date of access: March 10, 2008].

- ↑ ALL, Susan; GILLIGAN, Chris. Visualising Migration and Social Division: Insights From Social Sciences and the Visual Arts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, [S.l.], v. 11, n. 2, may. 2010. ISSN 1438-5627. Available at: <http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1486/3002>. Date accessed: 18 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ GURUGE, Sepali et al. Refugee Youth and Migration: Using Arts-Informed Research to Understand Changes in Their Roles and Responsibilities. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, [S.l.], v. 16, n. 3, aug. 2015. ISSN 1438-5627. Available at: <http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2278/3861>. Date accessed: 18 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ Frey, Ada F. & Cross, Cecilia (2011). Overcoming poor youth stigmatization and invisibility through art: A participatory action research experience in greater Buenos Aires. Action Research, 9(1), 65-82.

- ↑ BRUSLÉ, Tristan. Living In and Out of the Host Society. Aspects of Nepalese Migrants' Experience of Division in Qatar. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, [S.l.], v. 11, n. 2, may. 2010. ISSN 1438-5627. Available at: <http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1482/2992>. Date accessed: 18 Feb. 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 den Besten, O. (2010). Visualising Social Divisions in Berlin: Children's After-School Activities in Two Contrasted City Neighbourhoods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(2). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1488/3008

Other

- Anstadt, Scott P. "Use of Second Life to Teach Cultural Diversity and Cultural Competency" (March 25, 2015). SoTL Commons Conference. Paper 162. http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/sotlcommons/SoTL/2015/162

- Bruckman, A. (1997). MOOSE Crossing: Construction, community, and learning in a networked virtual world for kids. Unpublished PhD, MIT.

- Cooper, V. (2009). Inter-cultural student interaction in post-graduate business and information technology programs: the potentialities of global study tours. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(6), 557-570.

- Corder, Deborah. & U-Mackey, Alice. (2015). Encountering and dealing with difference: second life and intercultural competence, Intercultural Education, DOI:10.1080/14675986.2015.1091213

- Crossman, J. (2003). Secular spiritual development in education from international and global perspectives. Oxford Review of Education, 29(4), 503-520.

- Crossman, J. E. 2011. “Experiential Learning About Intercultural Communication Through Intercultural Communication. Internationalising a Business Communication Curriculum.” Journal of Intercultural Communication. Accessed Feb 18, 2016. http://www.immi.se/intercultural/nr25/crossman.htm

- Dann, Hanns-Dietrich (1992). Variation von Lege-Strukturen zur Wissensrepräsentation. In Brigitte Scheele (Ed.), Struktur-Lege-Verfahren als Dialog-Konsens-Methodik. Ein Zwischenfazit zur Forschungsentwicklung bei der rekonstruktiven Erhebung Subjektiver Theorien (pp.2-41). Münster: Aschendorff.

- Deardorff, D. 2011. “Intercultural Competence in Foreign Language Classrooms: A Framework and Implications for Educators.” In Intercultural Competence: Concepts, Challenges Evaluation. Vol. 10, edited by A.

- Diehl, W. C., & Prins, E. (2008). Unintended outcomes in Second Life: Intercultural literacy and cultural identity in a virtual world. Language and Intercultural Communication, 8(2), 17.

- Diehl, William, C. and Prins, Esther, Unintended Outcomes in Second Life: Intercultural Literacy and Cultural Identity in a Virtual World, Language and Intercultural Communication (Impact Factor: 0.65). 05/2008; 8(2):101-118. DOI: 10.1080/14708470802139619 Research gate

- Earley, P.; Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence. Individual interactions across cultures. Stanford, California: Stanford Business Books.

- Eblen, A.; Mills, C.; Britton, P. (2004). Walking the talk: teaching intercultural communication experientially. Communication Journal of New Zealand, 5(2), 27-46.

- Frey, Ada F. & Cross, Cecilia (2011). Overcoming poor youth stigmatization and invisibility through art: A participatory action research experience in greater Buenos Aires. Action Research, 9(1), 65-82.

- Gibson, K.; Rimmington, G.; Landwehr-Brown, M. (2008). Developing global awareness and responsible world citizenship with global learning. Roeper Review, 30, 11-23.

- Gudykunst, W.; Ting-Tommey, S. (1996). Communication in personal relationships across cultures: an introduction. In Gudykunst, W.; Ting-Toomey, S.; Tsukasa, N. (eds.): Communication in Personal Relationships across Cultures, pp. 3-19, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Guo, Y. 2010. “The Concept and Development of Intercultural Competence.” In Becoming Intercultural: Inside and Outside the Classroom, edited by Y. Tsai and S. Houghton, 23–47. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Halualani, R. T. 2011. “In/Visible Dimensions: Framing the Intercultural Communication Course Through a Critical Intercultural Communication Framework.” Intercultural Education 22 (1): 43–54. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.549644.

- Hampden-Turner, Charles and Fons Trompenaars (1993), The Seven Cultures of Capitalism, Currency-Doubleday

- Harrison, J. ( 2001). Developing intercultural communication and understanding through social studies in Israel. The Social Studies, 92(6), 252-259.

- Heyward, M. (2002). From international to intercultural: Redefining the international school for a globalized world. Journal of Research in International Education 1 (1) 9-32.

- Hiller, G. G. 2010. “Innovative Methods for Promoting and Assessing Intercultural Competence in Higher Education.” Proceedings of Intercultural Competence Conference 1:144–168.

- Hofestede, G. (1984). Cultures consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Hofstede, Geert (1991), Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage Publications.

- Holliday, A. 2011. Intercultural Communication and Ideology. London: Sage.

- Jarmon, L., Traphagan, T., Mayrath, M., & Trivedi, A. (2008).Exploration of learning in Second Life in an interdisciplinary communication course. Paper presentation at American Educational Research Association (AERA). New York, New York.

- Kanter, Rosebeth Moss (1995). World Class: Thriving Locally in the Global Economy, Simon & Schuster.

- Kimmel, K., and S. Volet. 2012. “University Students’ Perceptions of and Attitudes towards Culturally Diverse Group Work: Does Context Matter?” Journal of Studies in International Education 16 (2): 157–181. doi:10.1177/1028315310373833.

- Leask, B. (2010). Beside me is an empty chair. The student experience of internationalisation. In Jones, E. (ed): Internationalisation and the Student Voice. Higher Education Perspectives, pp. 3-18. New York: Routledge Taylor Francis Group.

- Lummer, Christian (1994). Subjektive Theorien und Integration. Die Einwanderungsproblematik aus Zuwanderersicht, dargestellt am Beispiel von Vietnamflüchtlingen in Deutschland. Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

- Mak A.; Barker, M.; Logan, G.; Millman, L. (1999). Benefits of cultural diversity for international and local students: contributions from an experiential social learning program (The Excell Program). In Davis, D.; Olsen, A.; (eds.): International Education: The Professional Edge, a set of research papers presented at the 13th Australian International Education Conference, Education Australia, Freemantle, 1999.

- Mayo, Andrew (2003) ―Culture: The Mother of all Hurdles, Training Journal, (May), p. 36

- Miller, E.K. (1994) ―Diversity and its management: Training managers for cultural competence within the organization, Management Quarterly, (Summer), Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 1723.

- Mody, Bella & Gudykunst, William B. (2001). Handbook of international and intercultural communication. London: Sage.

- Morrison, Terri, Wayne A. Conway and George A. Borden (1997). Dun & Bradstreet’s Guide to Doing Business Around the World, Prentice-Hall

- Peacock, N.; Harrison, N. (2009). "It’s so much easier to go with what’s easy". "Mindfulness" and the discourse between home and international students in the united kingdom. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(4), 487-508.

- Perry, L. B., and L. Southwell. 2011. “Developing Intercultural Understanding and Skills: Models and Approaches.” Intercultural Education 22 (6): 453–466. doi:10.1080/14675986.2011.644948.

- Rosen, Robert (2000), Global Literacies, Simon and SchusterTrompennaars, Fons, and Hampden-Turner, Charles (1998). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business,2nded, McGraw-Hill

- Rosen, Robert H. (2000) ―In growing global economy, boost cultural literacy,‖ Computerworld (April 24), Vol. 34, No. 17, p. 35

- Rosen, Robert. (2000). Global Literacies: Lessons on business leadership and National Cultures, Simon & Schuster.

- Rossen, R.; Digh, P.; Singer, M.; Phillips, C. (2000). Global Literacies, New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Salmon, G., Nie, M., & Edirisingha, P. (2010). Developing a five-stage model of learning in second life. Educational Research.Special Issue: Virtual Worlds and Education, 52(2), 169-182. doi:10.1080/00131881.2010.482744

- Scheele, Brigitte & Groeben, Norbert (1988). Dialog-Konsens-Methoden zur Rekonstruktion Subjektiver Theorien. Tübingen: Francke.

- Scheele, Brigitte (1992) (Ed.). Struktur-Lege-Verfahren als Dialog-Konsens-Methodik. Münster: Aschendorff.

- Sheridan, V.; Storch, K. (2009). Linking the intercultural and grounded theory: methodological issues in migration research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(1), Art. 36, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0901363.

- Shiel, C. (2009). Global perspectives and global citizenship: understanding the views of our learners. The International Journal of Learning, 16(6), pp. 689-693.

- Smith, D. B., Desai, H., Cotner, J., & Kashlak, R. (2005). International Field Studies: Tools For Enhancing Cultural Literacy. Journal of College Teaching & Learning (TLC), 2(2).

- Stier, J. 2006. “Internationalisation, Intercultural Communication and Intercultural Competence.” Journal of Intercultural Communication 11: 1–12.

- Swift, C.; Denton, L. (2003). Cross-cultural experiential simulation in the global marketing classroom: Bafa-Bafa and its variants. Marketing Education Review,13(3), 41-51.

- Ting-Toomey, S.; Oetzel, J. (2001). Managing Intercultural conflict effectively. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Tung, R.; Thomas D. (2003). Human resource management in a global world: the contingency framework extended. In Tjosvold, D.; Kwok, L. (eds.): Cross-cultural Management Foundations and the Future. Hampshire, England: Ashgate.

- Turner, Y. 2009. “Knowing Me, Knowing You”, is There Nothing We Can Do?: Pedagogic Challenges in Using Group Work to Create an Intercultural Learning Space.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (2): 240–255. doi:10.1177/1028315308329789.

- Unesco (2009), Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue. World Report, home page PDF

- Vadura, K. (2007). Enhancing conceptions of global citizenship in international studies in teaching and learning in an online environment. The International Journal of Humanities, 5(3), 17-21.

- Vernon, R., Lewis, L., & Lynch, D. (2009). Virtual worlds and Social Work education: Potentials for “Second Life”. Advances in Social Work 10(2), 176-192.

- Ward, Colleen; Bochner, Stephen & Furnham, Adrian (2001). The psychology of culture shock. Hove: Routledge.

- Weidemann, Doris (2001). Learning about "face"—"subjective theories" as a construct in analysing intercultural learning processes of Germans in Taiwan. Forum Qualitative Socialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(3), Art. 20, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0103208 [Date of access: March 10, 2008].

- Witte, A. 2011. “On the Teachability and Learnability of Intercultural Competence: Developing Facets of the ‘Inter’.” In Intercultural Competence: Concepts, Challenges, Evaluations, edited by A. Witte and T. Harden. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Yamazaki, Y.; Kayes, C. (2004). An experiential approach to cross-cultural learning: a review and integration of competencies for successful expatriate adaptation. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 3(4), 362-379.

- Yu, Elena & Liu, William (1986). Methodological problems and policy implications in Vietnamese refugee research. International Migration Review, 20(10), 483-501.

![A map of her "subjective territory" by a 13-year-old German-American girl from the school in Zehlendorf. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[11]](/mediawiki/images/thumb/2/2b/Map-childs-environment-1.jpg/361px-Map-childs-environment-1.jpg)

![Drawing 3a (by a Turkish boy aged 14 in Kreuzberg) features a youth club and a football field. Reproduced from den Besten (2010)[11]](/mediawiki/images/6/65/Map-childs-environment-2.gif)