Design-based research

under construction, half-way usable ... rather read some articles you can find in the reference section.

Definition

- According to Collins et al (2004: 15):

- "the term "design experiments" was introduced in 1992, in articles by Ann Brown (1992) and Allan Collins (1992). Design experiments were developed as a way to carry out formative research to test and refine educational designs based on principles derived from prior research."

Design research was developed to address several issues central to the study of learning, including the following:

- The need to address theoretical questions about the nature of learning in context.

- The need for approaches to the study of learning phenomena in the real world rather than the laboratory.

- The need to go beyond narrow measures of learning.

- The need to derive research findings from formative evaluation.

(Collins et al (2004: 16).

According to Reeves (2000:8), Ann Brown (1992) and Alan Collins (1992) defined critical characteristics of design experiments as:

- addressing complex problems in real contexts in collaboration with practitioners,

- integrating known and hypothetical design principles with technological affordances to render plausible solutions to these complex problems, and

- conducting rigorous and reflective inquiry to test and refine innovative learning environments as well as to define new design principles.

According to the Design-Based Research Collective (2003):

- First, the central goals of designing learning environments and developing theories or “prototheories” of learning are intertwined. Second, development and research take place through continuous cycles of design, enactment, analysis, and redesign. Third, research on designs must lead to sharable theories that help communicate relevant implications to practitioners and other educational designers. Fourth, research must account for how designs function in authentic settings. It must not only document success or failure but also focus on interactions that refine our understanding of the learning issues involved. Fifth, the development of such accounts relies on methods that can document and connect processes of enactment to outcomes of interest.

See also the discussion about design science.

What is DBR ?

Design-based reasearch (DBR) in education is probably very old, but recent interest can be traced back to the early nineties, e.g. Brown (1992) and Collins (1992).

More recently, special issues of Educational Researcher (e.g. Kelly 2003), the Journal of Learning Sciences (e.g. Barab 2004) and the Educational Psychologist (e.g. Sandoval & Bell 2004) reopened the debate. In addition some researchers joined in the Design Based Research Collective.

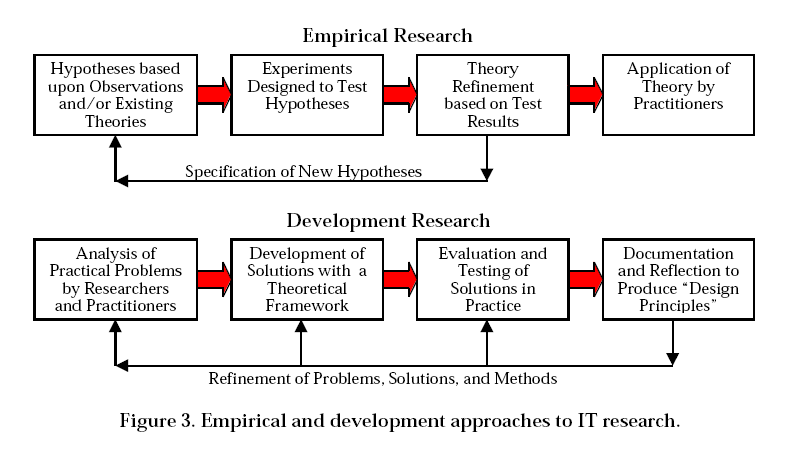

Reeves (2000:9) draws a clear line between research conducted with traditional empirical goals and that inspired by development goals leading to "Design Principles":

Action orientation

There is clearly an action-research oriented perspective, i.e. researchers must try to change things.

- The overall goal of research within the empirical tradition is to develop long-lasting theories and unambiguous principles that can be handed off to practitioners for implementation. Development research, on the other hand, requires a pragmatic epistemology that regards learning theory as being collaboratively shaped by researchers and practitioners. The overall goal of development research is to solved real problems while at the same time constructing design principles that can inform future decisions. In Kuhn's terms, these are different worlds." (Reeves, 2000: 12).

Situatedness and complexity

Context, i.e. situation-specific knowledge is an other important feature:

- ``A core part of design-based research as applied work involves situating the work in "naturalistic contexts".´´ (Barab & Squire, 2004: 11)

- Prototypically, design experiments entail both engineering particular forms of learning and systematically studying those forms of learning within the context defined by the means of supporting them. This designed context is subject to test and revision, and the successive iterations that result play a role similar to that of systematic variation in experiment. (Cobb, diSessa, Lehrer, & Schauble (2003:9)

Related to complexity and situatedness is the idea of iteration.

Theory as output

DBR often produces theory as output, in particular an instructional design model with a design rule at its heart.

Such theory is often very contextual and not necessarily applicable to a wider context, i.e. it needs futher corroboration with more traditional research approaches.

Reeves's recommendations

Verbatim quote from Reeves (2000:12):

- Focus on chronically difficult problems related to human learning and performance.

- Engage teachers, students, and colleagues in long-term collaborative research agendas.

- Carefully align any prototype technological solutions with instructional objectives, pedagogy, and assessment.

- Clarify the theoretical and practical design principles that underlie prototype technological solutions, and conduct rigorous studies of these principles, their inherent assumptions, their implementation, and their outcomes in realistic settings.

- Share the results of your design experiments in multiple ways, including refereed and commercial publications, web-pages, conferences, and workshops.

- Expect to work very hard. Be patient and persevere. And enjoy the challenge and reward of a career worth having for its contributions to the greater good.

Links

References

- Barab, S. A., & Kirshner, D. (Eds.) (2001) Special issue: Rethinking methodology in the learning sciences. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 10(1&2), 1-222.

- Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1)

- Brown, A. L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2(2), 141-178.

- Cobb, P., diSessa, A., Lehrer, R., Schauble, L. (2003). Design experiments in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 9-13. [1]

- Collins, A. (1992). Towards a design science of education. In E. Scanlon & T. O'Shea (Eds.), New directions in educational technology (pp. 15-22). Berlin: Springer.

- Collins, Alan., Diana Joseph & Katerine Bielaczyc, Design Research: Theoretical and Methodological Issues, The Journal Of The Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15-42.

- Edelson, D. C. (2001) Design research: What we learn when we engage in design. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 11(1), 105-121.

- Kelly, Anthony, E. (2003), Research as Design, Educational Researcher, 32 (1), 3-4.

- Thomas C. Reeves, Enhancing the Worth of Instructional Technology Research through Design Experiments and Other Development Research Strategies, Paper presented on April 27, 2000 at Session 41.29, International Perspectives on Instructional Technology Research for the 21st Century, a Symposium sponsored by SIG/Instructional Technology at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA, USA. [2]

- Sandoval, William A. & Philip Bell (2004), Design-Based Research Methods for Studying Learning in Context: Introduction, Educational Psychologist, Vol. 39, No. 4: pages 199-201.

- The Design-Based Research Collective (2003) Design-Based Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational Inquiry. Educational Researcher, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 5